VS Naipaul wrote with a precision that left readers unsettled and awed. As his centenary nears, we revisit the writer who turned exile into art

By

VS Naipaul was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2001, a decade after receiving his British knighthood, given for his body of work rather than a single title. The international reaction to this honour reflected the writer’s outstandingly polemical life. As was to be expected, the president of his native Republic of Trinidad and Tobago sent a letter of hearty congratulations. Somewhat less complimentary was the response in the Iranian press, which denounced Naipaul as a spreader of hatred. He was invited to pay an official visit to Spain, Indian politicians lauded his work, an editorial in The New York Times extolled his writings, while the Muslim Council of Britain denounced the award as a gesture of cynicism.

Naipaul was fully aware of, and ostensibly quite indifferent to, his reputation for causing offence, as he expressed in his Nobel acceptance lecture: ‘My background is at once exceedingly simple and exceedingly confused.’ Naipaul’s biographer, Patrick French, put his finger on the button when he said that Naipaul’s half- century of literary output seemed less significant than his reputation for provoking heated debate.

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul was born in Trinidad in 1932, with writing in his blood. His father, Seepersad, was a contributor to several Trinidadian publications.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

VS Naipaul travelled to the UK at the age of 18 on a scholarship to University College, Oxford. From that time, his life and his art became a series of arrivals and departures as he sought to define his place in several worlds. He began to write four years after his arrival in Britain, launching a career that would see the publication of more than 30 novels and works of non-fiction spanning five decades, before his death in 2018 at the age of 85. By that time, in spite of his widely condemned belligerence, Naipaul had accumulated a plethora of literary prizes.

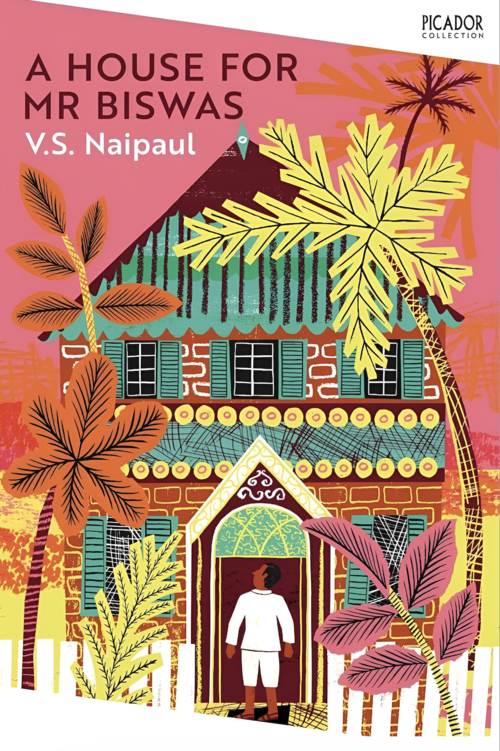

Naipaul’s literary career took flight when he was 29, with the publication of his fifth and most highly acclaimed stand-alone novel, A House for Mr Biswas. The plot in many ways mirrors the author’s own conflictive existence. The protagonist is a clever and droll figure, but one who can also be callous and insensitive. The story is set in Trinidad and involves the search for individuality. Throughout the narrative, Naipaul offers a detailed portrayal of Trinidadian life, told through the complex and often contradictory Mr Biswas.

VS Naipaul’s journeys took him to India, the birthplace of his grandfather, South America and Africa, and back to the Caribbean. His descriptions of these places are imbued with tales of cultures in upheaval. In many ways the archetypal Englishman, Naipaul (with the single exception of one early minor novel, Mr Stone and the Knights Companion) never published a book with a British setting – until the release in 1987 of The Enigma of Arrival, a story set in the countryside of Naipaul’s adopted Wiltshire, in and around a cottage near Stonehenge.

In his own words, the story had become ‘more personal, my journey, the writer’s journey.’ Though published as a novel, it’s clearly drawn from Naipaul’s own experiences – a tale of literary landscape and change. The narrator laments the encroachment of modernity: ‘Land is not land alone, something that simply is itself. Land partakes of what we breathe into it, is touched by our moods and memories…’ It’s as much autobiography as fiction.

Naipaul shared his Wiltshire refuge with his wife, Patricia Ann Hale, a teacher he met at the University of Oxford in 1952. Theirs was a 40-year companionship, during which Patricia acted as editor and supporter throughout her husband’s career, until her death from liver cancer in 1996. Two months after Patricia’s death, Naipaul married Nadira Khanum Alvi, a young divorcee and Pakistani journalist.

Naipaul’s hostile views of life in former British colonies earned him more than a few enemies within the literary world, as well as among the general public. That he got away with calling African societies ‘primitive’ and ‘barbaric’ might reflect the fact that he himself wasn’t a white European. Yet despite his outrageous comments, the popularity of his books kept him in the limelight long before the onset of ‘cancel culture’.

It took Naipaul nearly three decades to complete his India Trilogy. The titles – An Area of Darkness, A Wounded Civilisation and A Million Mutinies Now – express both his fascination with and deep pessimism for post-colonial India. By that time, Naipaul had amassed a surfeit of literary awards, including the Booker Prize in 1971 for his novel In a Free State, whose dominant theme is the price of freedom. The book, set variously in Egypt, America, Africa and Britain, comprises a collection of tales exploring European colonialism and the vagaries of power.

Naipaul’s final book, a work of non-fiction published in 2010, was The Masque of Africa: Glimpses of African Belief. It does exactly what its title promises, offering insights into Africa’s diverse belief systems as Naipaul travelled from Uganda to South Africa, talking to people about their spiritual views. Even in this final work, Naipaul stirred controversy, with British novelist Robert Harris condemning it as ‘toxic’. As usual, Naipaul reacted with indifference to both praise and censure.

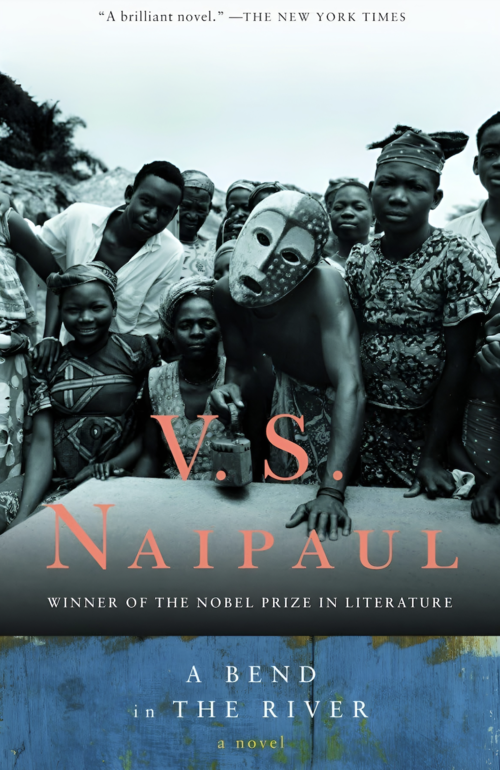

Naipaul’s last great novel, A Bend in the River, published in 1979, stands as a testament to his fascination with Africa. The setting is an unnamed country in post- colonial Central Africa. The narrator, Salim, is a young man from an Indian family of traders long resident on the coast. This ‘bend in the river’ is a microcosm of post-colonial Africa – a scene of chaos, violent change, warring tribes, isolation and poverty. From this turbulent landscape emerges one of Naipaul’s most potent works, a moving story of historical upheaval and social breakdown. American novelist John Updike applauded its range of human insight, saying that in his search for underlying social causes, Naipaul ranked as a ‘Tolstoyan spirit’.

American travel writer Paul Theroux was one of Naipaul’s bitterest enemies for some 15 years. Naipaul, who had long suffered from ill health, died shortly after their reconciliation. Theroux was moved to pay tribute, calling him ‘one of the greatest writers of our time’, adding, ‘He also never wrote falsely.’

Naipaul left a legacy of contradictions – in many ways the archetypal writer of the shifting, migratory 20th century. His life was a series of journeys between Old World and New, a sometimes snappish mediator between continents. The New York Times literary critic Dwight Garner, reporting Naipaul’s death, hailed the writer for his suppleness, wit and unsparing eye for detail. ‘He could seemingly do whatever he wanted,’ Garner wrote. ‘What he did want, it became apparent, was to rarely please anyone but himself. The world’s readers flocked to his many novels and books of reportage for his fastidious scorn, not for his large heart. In his obvious greatness, in the hard truths he dealt, Naipaul attracted and repelled.’

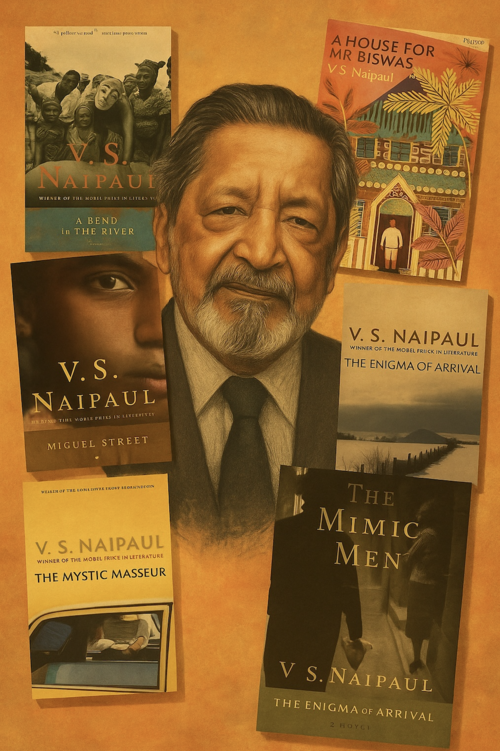

Eight VS Paul books to explore

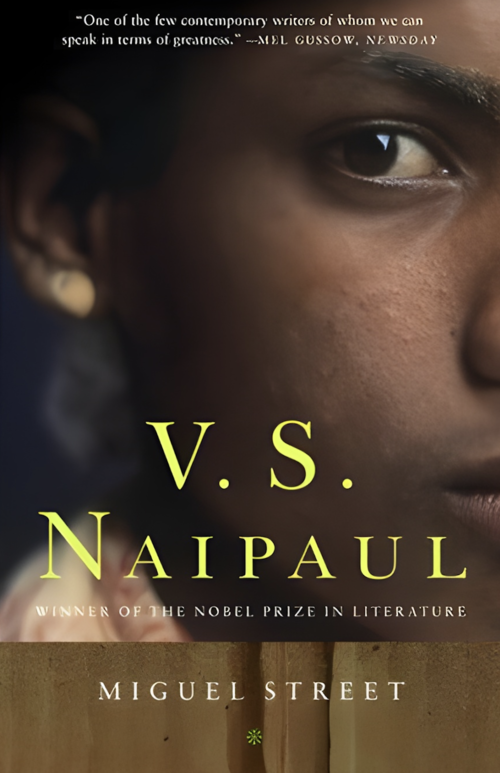

Miguel Street – 1959, linked short stories

Miguel Street is a series of interlinked vignettes set in wartime Trinidad, narrated by a boy growing up in Port of Spain. Through characters such as Mr Popo, the carpenter (who never finishes anything), and B Wordsworth, the ‘poet’ who never writes past the first line, Naipaul evokes

a community of dashed hopes, quiet quirks and small dramas. Each story captures a slice of life – from idle dreamers to eccentric neighbours – and together they form a portrait of collective stagnation and longing. As the book closes, the narrator escapes Miguel Street, underscoring themes of aspiration and departure.

The Mystic Masseur – 1957, comic novel

Naipaul’s first published novel follows Ganesh Ramsumair, a frustrated teacher who drifts through roles as masseur, spiritual healer and eventually politician in colonial Trinidad. The book is a satirical exploration of ambition, identity and the façade of success – Ganesh’s rise is as much about self-invention and illusion as it is about achievement. It established Naipaul’s early voice of ironic distance and cultural critique in a colonial setting.

A House For Mr Biswas – 1961, novel

This is often considered Naipaul’s masterpiece. Mohun Biswas, an Indo-Trinidadian man, battles fate, family and society while seeking the dignity of owning his own home. The narrative traces his peripatetic life across households and fields, always chasing the dream of rootedness. The novel’s power lies in how it frames a personal struggle – for respect, autonomy and identity – against the burdens of colonial Trinidad, patriarchy and social expectation. It’s both a deeply local story and one with universal resonance.

The Mimic – 1967, novel

In The Mimic Men, Naipaul casts a more fractured, psychological gaze: Ralph Singh, a politician from a fictional Caribbean island, reflects in exile on his dislocations, mistakes and illusions of self. This is a turning point in Naipaul’s work – less about external narrative progression and more about interiority, failure and the uneasy inheritance of both colony and exile.

A Bend in the River – 1979, novel

Set in a post-colonial African country, A Bend in the River follows Salim, a man of Indian descent who moves inland to a frontier town on a river bend. As political turbulence and decay unfold, Salim’s attempt to make a life becomes an allegory of post-independence instability. Many readers see this as one of Naipaul’s most potent meditations on power, alienation and the ambivalent promise of freedom.

The Loss of El Dorado – 1969, non-fiction/history

Stepping beyond fiction, The Loss of El Dorado is a historical investigation of Trinidad and the Caribbean – colonial rivalries, the lure of gold, the making of plantation economies and political legacies. It shows Naipaul at work as both historian and cultural critic, tracing how the past shapes not just material institutions but collective psyches.

The Enigma of Arrival – 1987, novel/semi-autobiographical

Set largely in Wiltshire, England, The Enigma of Arrival uses the natural landscape as a mirror for internal change. The narrator’s reflections on place, time and transition turn rural England into a battleground of memory and belonging. Although published as fiction, the book draws heavily from Naipaul’s lived experience. Its slow, observational style marks a maturity in his voice – less polemic, more meditative.