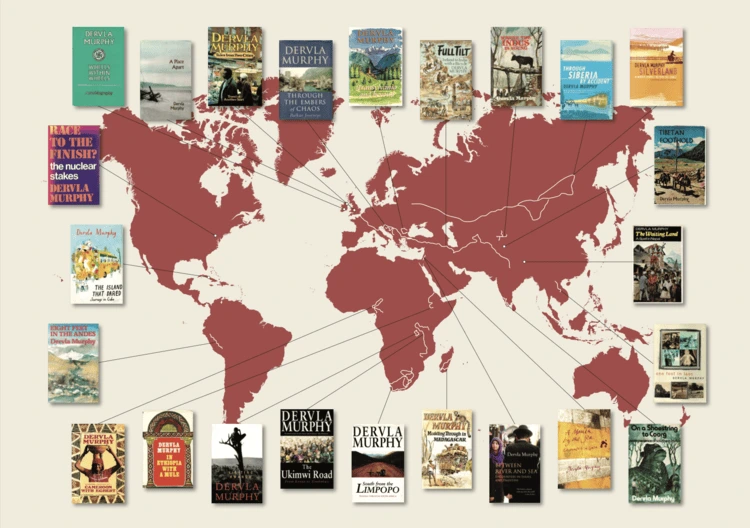

The life and legacy of travel writer Dervla Murphy, whose indomitable journeys by bike, donkey and foot inspired a generation

By Ethel Crowley

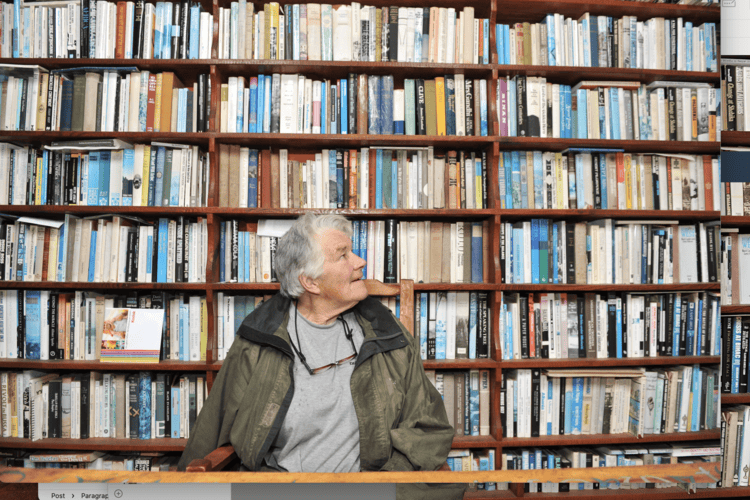

Dervla Murphy (1931–2022), one of the world’s best-known contemporary travel writers, was a self- confessed bibliomaniac. She had been a voracious reader since she was a small child in Lismore, County Waterford, in the 1930s.

Her Dublin parents had upper- middle-class tastes, rendering her home environment cultured and bookish. Her father was a scholarly librarian and her mother his intellectual match. Her paternal grandfather also exerted a strong influence on Dervla’s childhood reading.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

She evolved into a woman who was consumed by books: reading, writing, reviewing and discussing books were at the core of her very being. Her home was a library, arranged by region. Book talk formed a large part of our many, long, kitchen-table conversations over the years at her home.

Formal schooling had a negligible influence on her life; she finally left school at 14 to care for her severely disabled mother. This independent autodidact went her own way. During her teenage years, she read the complete works of the art historian John Ruskin and the entire canon of great English novelists, with George Eliot’s Middlemarch being her favourite. Her greatest desire had always been to become a famous writer herself.

At the age of four, she had pointed to the author’s name on a book cover and assertively declared: ‘When I’m grown up, I’m going to write books and have my name there.’

Her early love for writing was nurtured by her unconventional parents: she had to write them stories as Christmas and birthday gifts. She was given presents of an atlas and a bicycle for her tenth birthday. She firmly decided at that point that she was going to cycle to India, as it was the furthest distance one could cycle on a continuous land mass.

She always bravely explored her own local area, loving to cycle around west Waterford and south Tipperary, and swim in the Blackwater River. At the age of 11, she did an 80-kilometre round trip in 12 hours. She revelled in pushing her body to its limits. She told me that her mother helped to instil courage in her: ‘At the age of 16, in 1947, it was my mother who suggested that I cycle through the Continent alone – not many mothers did that!’

She then took cycling trips to the UK, France, Germany and Spain as a teenager and young adult. Challenging her curious mind and her strong, athletic body became a way of life from a young age. However, since she was more or less the sole carer for her mother throughout her teens and 20s, her adventures were severely curtailed for a long time.

1960s

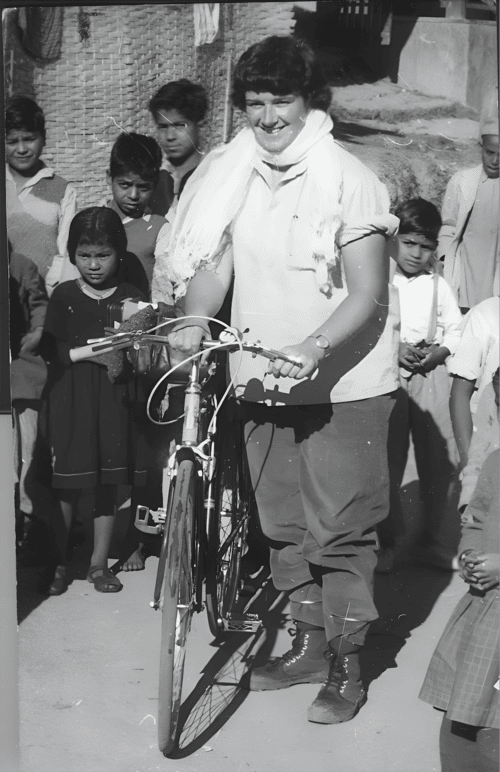

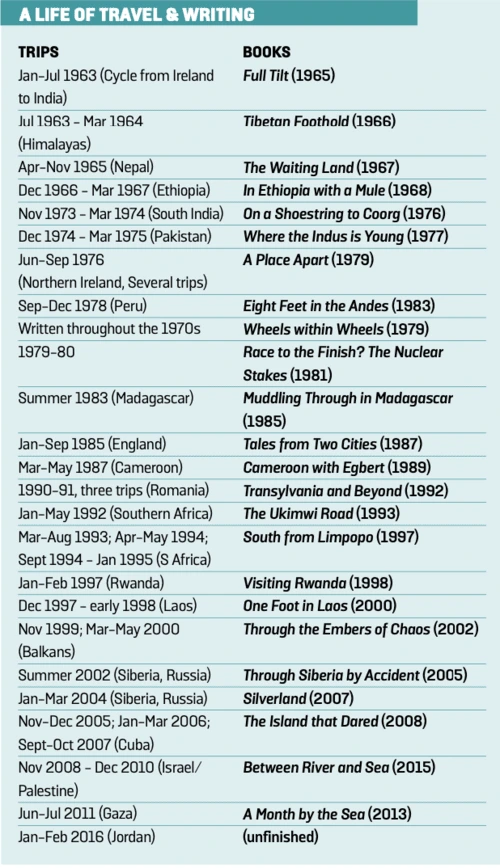

Following the deaths of both of her parents in January 1963, Dervla fulfilled that life-long dream of cycling to India. Finally unfettered, she said that the feeling of liberty ran through her body like a mild electric shock. This trip was immortalised in her first book, Full Tilt, published by John Murray publishers.

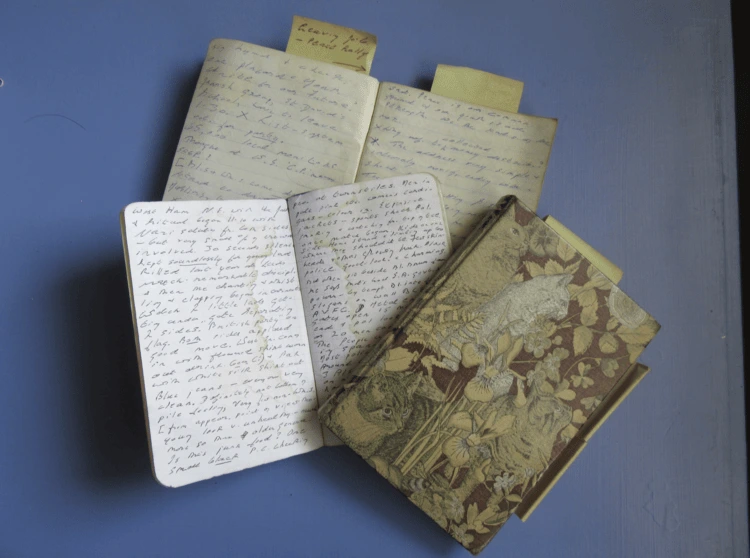

She spent the latter half of 1963 volunteering at a home for Tibetan refugees in the Indian Himalayan town of Dharamshala. On her return to London, she took some time to recover from illness. Having become enamoured with Asia, she then spent six months in Nepal in 1965. She had posted home letters to her friend Daphne, which ultimately constituted her book notes.

She wrote Tibetan Foothold and The Waiting Land ‘by candlelight’, as she said, while staying with her on Inis Oírr, off Ireland’s west coast, ‘throughout dramatically beautiful Aran winters’.

She then left for a three-month trip to Ethiopia in December 1966. Hiking across remote areas with a mule named Jock, she was robbed by bandits. It was the one incident (among so, so many) when she thought she was about to die. Back home, her life changed dramatically and wonderfully in 1968, with the birth of her daughter Rachel.

1970s

Dervla wrote her unflinchingly honest autobiography Wheels within Wheels during the 1970s while Rachel was a child. She said that she wrote it primarily for Rachel’s benefit and never intended it for publication, until Jock Murray unearthed it at her home. His instincts proved correct; it has become one of her most loved books.

Dervla returned to India in November 1973, ‘with foal at foot’, bringing five-year-old Rachel on her first big trip. Coorg is the story of spending some months in the southern region of the Western Ghats. She saw India through the bright, curious eyes of her child.

Continuing the Asian theme, Indus is a report on the hard winter they both spent hiking in the mountains of Baltistan, Pakistan with a pack-horse named Hallam. An endurance test for all three, the trip spawned a written account that is downright heart-stopping in places.

A Place Apart was Dervla’s attempt to comprehend Northern Ireland, that region that was so familiar, yet so strange. She took enormous risks there: part brave, part foolhardy. The brilliant observations and conversations in the book show how well she connected with people of all hues, and how empathetic and unthreatening she appeared, during some of the most dangerous years of the ‘Troubles’.

1980s

Dervla’s first book of the 1980s was her condemnation of nuclear power. This became a concern for her, as she had passed near the site of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the USA in March 1979.

She conducted an enormous amount of research on the subject over a two-year period; she was very proud of the work until the end. She told me recently: ‘These days, climate-worried people are accepting the nuclear industry’s propaganda that it’s “clean” and the obvious energy solution. What about the miners of the uranium, and what’s to be done about nuclear waste?’

Her book on Peru was published in 1983, despite her having been there with Rachel in autumn 1978, where

she celebrated her tenth birthday. At the time, she thought this trip would probably be the last one with Rachel. However, she featured in several books after that, as Dervla’s able navigator and hardy travelling companion.

The next book, on Madagascar (1985), was based on a trip taken by them both in summer 1983. Madagascar has retained some very rare species of flora and fauna due to its isolated position. She was terrified of the effects of the twin dangers of mineral exploitation and tourism there. She considered the loss of a single species, no matter how apparently ugly or ‘useless’, to be an enormous loss to humanity.

In 1985, Dervla began studying the subject of troubled race relations in England. She stayed in Manningham in Bradford (predominantly South Asian) and Handsworth in Birmingham (predominantly Black) for about three months each. Tales from Two Cities is an important contribution on this topic. She shared details of conversations with people she met in local bars and in their homes. She was also caught up in riots during her time there and wrote brilliant reportage on those events.

Her 1987 trip through Cameroon with Rachel and Egbert the mule resulted in her next book, published in 1989. The main memory Dervla retained of that trip was the agony of a tooth abscess she developed while there; she told me it was like a volcano erupting inside her head.

1990s

Dervla had been entranced as a child by Walter Starkie’s book Raggle Taggle on the Gypsies of Transylvania. She decided to go to Romania as soon as she possibly could, mere days after the fall of the Ceausescu regime on Christmas Day, 1989.

She saw in the 1990s on an eastbound bus. This was her first peek behind the Iron Curtain, having been curious about it for decades. Transylvania was the result.

In January 1992, having bought herself an expensive mountain bike for her 60th birthday, Dervla embarked upon ‘a four-month mystery tour’ – a circuitous route from Kenya to Zimbabwe. Her report on this huge African trip became Ukimwi Road. with AIDS as its core theme.

Dervla had first wanted to go to South Africa in 1983 but was refused a visa. However, it remained on her mind. She ultimately took three trips there to gather material for the epic Limpopo, in 1993, ’94 and ’95 – compulsory reading for those interested in South Africa’s transition from apartheid.

She intended to go mountain- trekking in Rwanda in January/February 1997 but was prevented from doing so. Her trip turned out to be more controlled and monitored than she would have liked because of ‘tiresome security problems’. She needed freedom to roam.

On a roll now, Laos was next. She trekked in places that no doubt no longer exist, as the pristine countryside was subjected to such a feeding frenzy by loggers, hunters, road developers, miners and energy companies. She met people who were unable to farm their land because of unexploded ordnance and therefore starving – directly affected by the aftermath of the Vietnam War, many years afterwards.

2000s

Dervla travelled to the Balkan region a few times, but the main trip was in spring 2000, four and a half years after the Bosnian war. She very strongly opposed NATO’s military intervention in 1995 and its continued ‘peace- keeping’ role there. Tensions persisted until 1999, shortly before Dervla spent time there.

In 2002, she decided to go to Siberia, but she hurt her knee badly on that trip. She returned in early 2004, as she had fallen in love with Lake Baikal and longed to see it again. She really, really loved cold places.

Dervla first visited Cuba with Rachel and her three daughters in late 2005, then immediately returned alone

in early 2006 and again in autumn 2007. She loved Havana despite her usual antipathy to cities, because, she surmised, Habaneros behaved more like villagers than city dwellers. She retained her admiration for Castroism after her time there, despite the everyday hardships endured by Cubans.

2010s

The month she turned 77, Dervla embarked upon travel in Israel and Palestine. Between November 2008 and December 2010, she spent three months in Israel and five months in the West Bank. Constantly curious and oblivious to hardship, she spent some time on a kibbutz and also lived in Balata refugee camp near Nablus. Between River and Sea tells those fascinating stories.

In June 2011, at the age of 80, she spent an arduous month in the Gaza Strip. The material gathered during that month was enough to fill a separate book. Her trail is now probably reduced to rubble and her informants at least traumatised and displaced, if not dead.

The two books that resulted provide a rare insight into this Middle Eastern region. She was clear that this was not a war between equals. The might of the US-backed Israeli army had made the daily lives of ordinary Palestinians a living hell.

She nevertheless became a passionate advocate for the One- State Solution, the creation of a single, shared democratic space. Her detailed observations of the Northern Irish and South African cases gave her a sliver of hope for the possibility of fulfilling this dream. Had she lived to see the developments since October 2023, I imagine that hope would have been thoroughly and terminally quenched.

Her final trip was to Jordan in early 2016 at the age of 85. However, a fall brought her home early and fate decreed that this work was not to be.

Original thinker

Dervla Murphy thrived on the joyous challenge of an open road to be travelled and a blank page to be filled. She was

a disciplined and thorough researcher, becoming one of the most respected travel writers that has ever lived. She was a truly original thinker, influenced by Buddhism, socialism, feminism and environmentalism.

She told me, however, that she was philosophically a humanist. She said, ‘People are in control of the world and they need to behave responsibly when exercising that control.’ She attempted to understand the countries she visited by reading widely, taking her time and speaking openly to everyone. She was well read and down to earth in equal parts.

She did ‘slow travel’ long before the term was coined, blazing a trail for the rest of us. She pushed herself hard in every way, tolerating the toughest conditions imaginable on the road.

She was a powerful role model, especially in terms of solo travel for women and positive ageing. She advocated making informed choices, seeing things for yourself, making up your own mind and striding out into the world with

optimism and confidence. She quietly demonstrated how to shake off the weight of convention, listen to our wild inner selves and hit the road. With gusto.

Ethel Crowley is an Irish sociologist and writer. She is the editor of Life at Full Tilt: The Selected Writings of Dervla Murphy published by Eland (www.travelbooks.co.uk)