The story of a family ripped apart by the war in Ukraine – a harrowing & revealing insight into what Russians really feel about the conflict

Words and photographs by Howard Amos

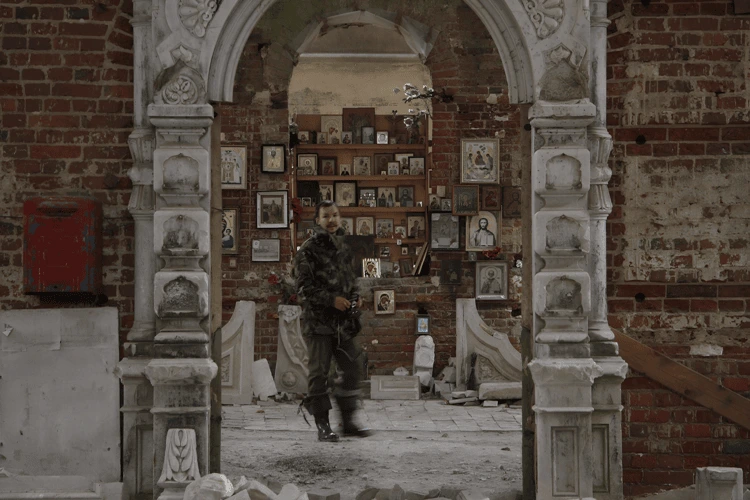

In his moving account of recent Russian history, author and journalist Howard Amos sheds light on the tragic impact that decades of deprivation, violence and autocratic rule have had on the nation’s people. His book Russia Start Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire focuses on the Pskov Region, the western edge of the vast country, bordering EU and NATO territory.

He knows the area and its people well, having visited it regularly as a journalist and previously as a student volunteer in one of Russia’s grim orphanages. Here, we run an edited extract telling the story of a family ripped apart by the war in Ukraine – a revealing and harrowing insight into what Russians really feel about Putin’s conflict. It’s accompanied by a selection of Howard’s photographs illustrating a troubled region in desperate times.

Svetlana pleaded with her husband not to go and fight in Ukraine. ‘I tried everything: “What about the children? How will it affect the kids? And what about us?” But nothing worked,’ she said. ‘What else could I have done? If words didn’t help, what could I have done? Maybe I should have fought him, or tied him to the bed with handcuffs?’

Related articles:

After visiting a Pskov military recruitment office in late 2022 to put his name forward as a volunteer, Mikhail, a thickset 31-year-old with mousy brown hair, got a phone call on Svetlana’s birthday to report for active service.

He bought himself some equipment, including a sleeping bag, and left for training at a military base north of St Petersburg two days before New Year.

The last time Svetlana and Mikhail saw each other before his deployment was a month later when she took the two children to visit him at the base. They spent five hours together. A photo taken that day showed the four of them in a café: Mikhail was in a military jacket and tight-lipped, Svetlana smiled slightly at the camera. The following day, he was put on a train to Belgorod, the closest Russian city to the Ukrainian border.

It’s hard to miss the military in Pskov Region. One of the first associations most Russians not from Pskov have with the city is that it’s home to the 76th Guards Air Assault Division. Paratroopers in their sky-blue berets are a common sight on the streets, and the planes they use for practice jumps circle endlessly overhead.

While driving near the town of Ostrov on a winter afternoon, the blue sky dusted with tufts of clouds, I remember seeing several KA-52 ‘Alligator’ attack helicopters skimming above the distant tree line. There were no other cars on the road. When one of the helicopters approached us head-on, just a few hundred metres above the road, it dipped its nose as if lining up to open fire.

At the forefront of almost every major conflict in Russia’s post-Soviet history, the 76th saw heavy action in both Chechnya and Ukraine. It is considered an elite force with a reputation for brutality and bravery. Paratroopers have a professional holiday on 2 August that is notorious for its displays of brawling, violence and drunkenness. It’s an excuse for ex-paratroopers, now mostly balding and sporting beer bellies, to don their berets, consume large amounts of vodka, jump in fountains, and roam the streets looking for trouble. In Pskov, they have two large bases: one on the western side of the city; one in the east.

At the entrance to the on in the west, there is a large poster with a picture of the Earth with a tank, helicopter, plane and several masked soldiers that reads: ‘Russia’s borders have no limits.’ Mikhail was raised on the edge of Lake Peipus to the north of Pskov, and the Russian armed forces would have been part of the backdrop to his day-to-day life.

As the war raged in Ukraine, I found the profile of Mikhail’s wife, Svetlana, on social media. The state of the armed forces, and Russia’s losses, are closely guarded secrets and, fearing official reprisals, the relatives of Russian soldiers are usually reluctant to talk to Western journalists. Many Russians also believe they are fighting NATO, equating Westerners with the enemy. However, Svetlana agreed to an interview.

A short woman with large, black glasses, Svetlana appeared on the call with her youngest daughter in her arms. Her hair was straight, and, as she spoke, she moved around the house doing odd jobs. Svetlana said she was not the only one who had argued with Mikhail over his decision to go to war – his mother and friends also begged him to reconsider.

Apart from the obvious danger, there were plenty of arguments for staying: Mikhail’s job in a cement factory made him the family’s sole breadwinner, and the couple had two young daughters. The eldest, Dariya, was seven when Mikhail joined up. The younger, Yevdokiya, just six months.

It’s true that Russia offers significant financial incentives for contract soldiers, which can mean men like Mikhail receive the equivalent of almost a year’s salary as a sign-on bonus. But Mikhail was not in debt, he was not prone to extravagant drinking binges, and, while the family was undoubtedly poor, they were not poverty-stricken. Nor was he motivated by ideas.

At least according to Svetlana, Mikhail did not believe he was defending his family, or liberating the oppressed people of Ukraine from a mythical ‘Nazi’ regime. He didn’t watch the news and had no interest in developments on the battlefield. He’d never been to Ukraine. The closest he came to an ideology was professing a desire to kill khokhli, an ethnic slur for Ukrainians. Instead, his decision seems to have been wrapped up in how he understood his masculinity, a child-like fascination for guns and explosions, and the traditional appeal of the armed forces in Russia as a social elevator.

Mikhail first told Svetlana he was interested in enlisting after Putin announced Russia’s partial mobilisation in September 2022. Over the course of several weeks, mobilisation hoovered up a few hundred thousand men for the army, which was then on the back foot as Kyiv reversed some of the gains Russia had made in the first weeks of fighting. Mikhail’s younger brother, Alexander, was one of those who received his call-up papers.

‘When mobilisation started, he said it would have been better if they’d taken him instead of his brother,’ said Svetlana. Perhaps Mikhail thought it was wrong that his younger brother was in danger while he was safe at home. Perhaps he was jealous to be missing out.

Either way, the war appeared to spark thoughts in Mikhail about what it meant to be a man. The pull of traditional masculinity is a powerful one, immediately understandable to most Russians, and has been used extensively in army recruitment campaigns. In one slickly made video from 2023, which also plays on the insecurities of those in low-paid jobs, a taxi driver, gym trainer and security guard are shown transformed into soldiers. ‘You’re a real man!’ flashes up on the screen. Followed by: ‘Be one!’

Svetlana believes that – ‘like all men’ – Mikhail was interested in ‘running around with a gun, grenades, mortars and riding on a tank’. Apparently, he told her shortly before departing that he’d ‘always wanted to do some fighting’.

Joining the army was one of Mikhail’s few life ambitions. He had enjoyed his year-long military service a decade earlier near Moscow, when he was likely regaled with stories about how professional soldiers were well paid, had a steady career and got financial perks, including a heavily subsidised mortgage. In other words, for a young man from a poor, rural community in Pskov Region, the army was a prestigious job that offered material, educational and social opportunities – and could imbue life with some obvious meaning.

Mikhail twice tried to enlist once he’d returned to civilian life after his military service, but was knocked back both times. Svetlana said he failed ‘psychological tests’, suggesting he was deemed unfit by a doctor, possibly because of some sort of mental illness, learning disability, or because he was judged to be a suicide risk. However, with Russia suffering a desperate shortage of manpower in Ukraine, all checks were scrapped – there were no longer obstacles.

Mikhail, of course, knew he was destined for the front lines. But it’s difficult to guess what he was expecting to find there, or whether he quite realised the level of physical danger to which he would be exposed. Perhaps he thought little beyond having a break from the humdrum reality of work, young children and family responsibilities.

If he’d known soldiers who’d already fought in Ukraine, he might have been more wary. Those serving in the 76th Guards Air Assault Division had been at the centre of some of the most intense battles of the early phase of the war. And, like other paratrooper units, they’d taken heavy casualties. After just six months of fighting, some estimates put Russia’s total paratrooper losses as high as 50 per cent killed or wounded from a pre-invasion force of some 45,000.

The Russian army had suffered a series of reversals during a Ukrainian autumn counter-offensives in Kharkiv Region in late 2022. In a bid to regain the momentum, and buoyed by an influx of freshly mobilised men, Russia launched a winter offensive at the start of the following year. At this point in the war, a major breakthrough for either side already seemed a distant prospect, with the fighting gradually becoming an attritional struggle.

Nevertheless, Russia committed tens of thousands of poorly trained troops and large quantities of armour to frontal assaults on eastern Ukrainian towns like Vuhledar, Marinka, Avdiivka and Bakhmut. The offensive began in late January with an unsuccessful attack on Vuhledar. According to a tally of losses kept by independent journalists, the first week of February saw more reports of Russian military deaths than any other week of the war up to that point.

It was at this moment that Mikhail arrived in Ukraine. Svetlana does not know when exactly he crossed the border, nor to what unit he was assigned – although it was nothing as prestigious as the 76th. She does know he was separated from those alongside whom he’d trained. We can guess that, as commanders became frustrated

by a lack of progress, new recruits were dispatched piecemeal to wherever they were needed.

The last time Svetlana spoke to her husband was on 4 February, the day before Dariya’s eighth birthday. Mikhail phoned to wish Dariya a happy birthday and say he was okay. They only chatted for a few minutes before the conversation was cut short because of a bad line. ‘I think he phoned before they departed for an attack,’ said Svetlana. Mikhail was killed four days later.

Svetlana never received any official information about the circumstances of Mikhail’s death. But she tried repeatedly to ring the number from which he’d contacted her that final time and, eventually, a man picked up. When she asked what had happened, he told her Mikhail was sleeping in a shelter when it was hit by a shell. Three others died alongside him in the blast. It’s not clear whether, by that point, Mikhail had taken part in an attack, or if he’d even fired his weapon in anger. ‘It seems that was his fate,’ said Svetlana. ‘He’d only just arrived, and then it was all over.’

The authorities carried out all the arrangements for the funeral, which was well attended by family, friends and local well-wishers. It took place in a church near where Mikhail had grown up, and he was accorded military honours, including a flag-draped coffin, the Russian national anthem and a military guard who discharged their rifles over the grave.

A few days after the funeral, one of Mikhail’s sisters posted a Photoshopped image of him on VKontakte, the Russian equivalent of Facebook, in which he is wearing military camouflage and holding two rifles. She captioned it with crying emojis and the words: ‘You are always in our hearts.’ Mikhail’s younger brother, then fighting in Ukraine, also posted photos as a sort

of online memorial, including several of Mikhail and Svetlana from a night in the village when they were much younger. They show Mikhail’s large, calloused hands embracing Svetlana while she grips him tightly by the lapel, as if afraid he’s going to get away.

The speed of events made everything seem particularly unreal, and Svetlana said she struggled to process what had happened. ‘We’d seen him less than a month ago, and now he was… in his grave. I still don’t believe it – it feels like he’s simply gone away for work and will be back again.’

When he died, Svetlana had known Mikhail for a total of 12 years. The two of them had been childhood sweethearts. Born in St Petersburg, Svetlana was removed from her family by social services aged five, and grew up in Russia’s orphanage system. She lived in several different orphanages before ‘graduating’ at the age of 18. Mikhail was raised in the countryside in a large family – he had seven brothers and sisters. His mother worked in a shop and remarried after the death of Mikhail’s father.

In Svetlana’s telling, their relationship was not one of great passion. She messaged Mikhail while he was doing his military service, and they kept in touch over the phone. After he returned, they began seeing each other. He was her first serious boyfriend. She said she was drawn to his air of responsibility, which made him seem adult beyond his years. ‘I thought he was already mature,’ she said. ‘He was serious about life, even though he was only 20.’

After leaving the orphanage, Svetlana moved to St Petersburg to study to be a nurse. Mikhail would come and see her in the city, and she would travel to visit him in the countryside. Unexpectedly, Svetlana got pregnant, and it’s here that their lives appear to bow to circumstance, and the inexorable weight of social expectation.

Svetlana said neither of them wanted a child, nor were they planning to marry. But that’s exactly what happened. ‘His relatives were like: “Come on, come on – this is what you have to do. Let’s put on a wedding and have some fun.” And that was how it was decided,’ Svetlana said. ‘Of course, all little girls dream about getting married, but, even so, I think you shouldn’t get married when you’re young… [But at that moment] all my girlfriends had already gotten married. It was happening faster and faster. And you looked at them and thought: maybe I want this as well.’ Svetlana was 21 when they tied the knot; Mikhail 23.

After the wedding, Svetlana abandoned her studies and moved to Gdov, a town near Lake Peipus, so they could live together. Mikhail had various farming jobs, including as a tractor driver. She worked in a nursery. In 2020, they returned to Slantsy, where they had been to school, and, with the money from the sale of a flat Svetlana inherited, they bought a house. Mikhail was hired by the town’s cement factory and Svetlana became a full-time mother.

Of course, nothing special had ever been expected of Mikhail or Svetlana when they were growing up – not by their teachers, family, nor orphanage staff. Staying out of trouble, getting married and starting a family was likely the most anyone could imagine for an orphanage girl and a boy from a remote village. Still, the absence of ambition in Svetlana’s life with Mikhail was striking.

Mikhail’s only interests appeared to be holding down a nine-to-five job and joining the army. Occasionally, Svetlana said he’d daydream about setting up a business – opening a garage or a timber-felling firm – but he never came close to getting such ideas off the ground.

Svetlana’s daily life hasn’t changed significantly since Mikhail’s death. She is now entitled to benefit payments of 44,000 roubles (£390) a month, which is enough to get by in Slantsy. ‘All the same it’s difficult when you’re alone,’ she admitted. ‘[But] what else is to be done? If I get drunk, would it be any easier? It would not be easier for the kids. And social services would be set on me because I was boozed up and the kids were feral. For what? That wouldn’t make anyone’s life easier. So, what can I do? You cry and cry.’

While she said she didn’t blame herself, Svetlana repeatedly came back to her role in Mikhail’s death in a way that suggested to me she did feel some guilt. This seemed to stem from a widely held understanding that men are infantile beings, passed from the care of mothers to dutiful wives. A good wife, the logic runs, should have been able to rid Mikhail of the notion of going to war. His departure for the front and subsequent death thereby implied that Svetlana was a bad wife – and a failure as a woman. Svetlana said she was often asked by others: ‘How could you have let him go?’ Svetlana also downplayed her grief, as if she was somehow unworthy.

Despite the death of her husband, the war for Svetlana was something that remained very far away: or, as she put it, ‘on another part of the planet’. She said news bulletins on state-owned television were full of lies, and, like Mikhail, she had no time for propaganda stories about the oppressed Ukrainian people, reconquering ‘Russian’ land, or a Nazi regime in Kyiv. Nor did she mention another common official justification for the invasion – that Russia was threatened by NATO (even though she lives just 15 kilometres from Russia’s border with Estonia, a NATO country).

In fact, Svetlana struggled to see any meaning at all in what was unfolding. ‘No-one understands why it’s happening, no-one understands how it will end, and it’s unclear what they’re trying to achieve. We don’t need that land. We live here quietly, peacefully and calmly. And out there, they’re just killing one another for reasons that are baffling,’ she said. Russian soldiers in Ukraine don’t know what they’re fighting for, according to Svetlana. ‘Many even say that it’s… just for kicks,’ she said. ‘And that the Second World War was a better war than what they’ve got going on.’

Yet, Svetlana wasn’t angry and didn’t blame anyone for Mikhail’s death. She levelled no accusations at the Russian state, which had been her guardian as she was shuttled between orphanages as a child, and then took away her husband. Fatalism saturated everything she said. Tragedies were something to be endured; your lot in life was preordained. Maybe, she wondered, Mikhail had been drawn to go off and fight by a ‘higher power’.

At the same time, like Mikhail, she expressed absolutely no empathy for Ukrainians who continue to suffer so terribly from Russian aggression. ‘I don’t have a drop of pity for anyone,’ she said.

The families of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine receive large compensation payments, and, occasionally, gifts from the local authorities. Svetlana described hers as ‘blood money’. But she did go to a ceremony in which the head of Gdov District presented her with Mikhail’s posthumous Order of Courage. In photos of the event, the diminutive Svetlana stands stiffly on an outdoor stage wearing a bright red dress, clutching the medal in one hand and a large bunch of flowers in the other. Dariya is next to her in a pale green dress.

A few months later, Slantsy updated a local war memorial, adding the names of Mikhail and other Russian casualties from Ukraine. At the ceremony, a group of uniformed kids from Russia’s Youth Army held up placards with photos of the dead as relatives laid flowers and officials made speeches. Svetlana, who was in the crowd, said she ‘cried and cried’. Of the 23 men commemorated on the memorial, nine died in the decade-long Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and separatist wars in Chechnya in the 1990s and early 2000s. Fourteen had been killed in less than two years of fighting in Ukraine. There is no memorial to Mikhail in Gdov District where he grew up, but Svetlana said she would like to see one erected.

‘That way it would be written into history,’ she said. ‘It’s true he only fought very briefly and wasn’t there for very long – but even still! It would have made him happy.’ She visits Mikhail’s grave every few months, but it’s 90 minutes in the car to the cemetery, and she can’t drive. She doesn’t take the children.

Svetlana seemed to have few plans for her future. She said she had not thought about remarrying. Apart from dreaming of a holiday at a Turkish resort or taking a cruise, there was nothing she wanted. With the two children, she existed from one day to the next, avoiding decisions that might disturb their routine. ‘Time flies,’ she said, speaking, not for the first time, as if her life was already drawing to a close. If you didn’t know Svetlana was only 30 years old, listening to her would make you think she was twice that age.

Even for Dariya and Yevdokiya, Svetlana’s hopes were rudimentary. ‘I would like them to grow up to be decent people, who don’t drink themselves into an early grave, get involved with bad company, or go to prison,’ she said. ‘I don’t know why, but in my head I’m already giving them away to be married.’

(Names have been changed in this account. Relatives of soldiers killed or wounded in the war who have talked to the press have been arrested and harassed)