MiCO tool gives conservationists and governments a powerful new resource to protect ocean wildlife

By

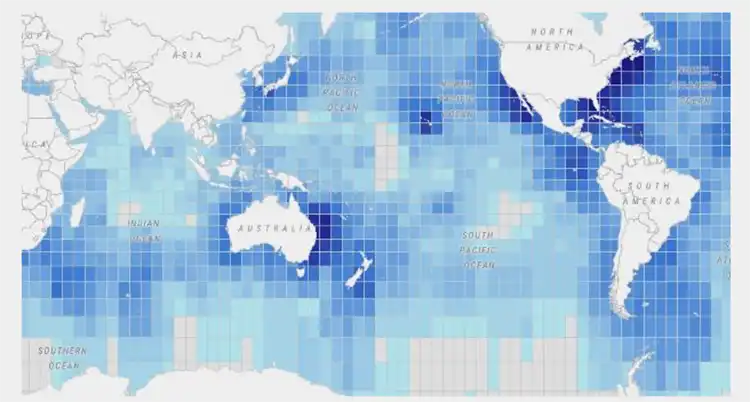

A groundbreaking interactive map has been launched to chart the migratory movements of more than 100 marine species — offering a vital new tool to help safeguard ocean biodiversity.

Developed by scientists at The University of Queensland (UQ) and Duke University, the Migratory Connectivity in the Ocean (MiCO) database bridges key information gaps for conservationists and policymakers.

Each grid square on the MiCO map contains species-specific data, giving researchers, governments, and international organisations unprecedented access to how animals move through ocean regions.

‘Covering 109 species including birds, mammals, turtles and fish, MiCO brings together thousands of records from more than 1,300 sources to map how marine animals traverse the world’s oceans,’ said Dr Lily Bentley from UQ’s Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science.

The tool highlights nearly 2,000 crucial habitats and underscores the importance of cross-border collaboration.

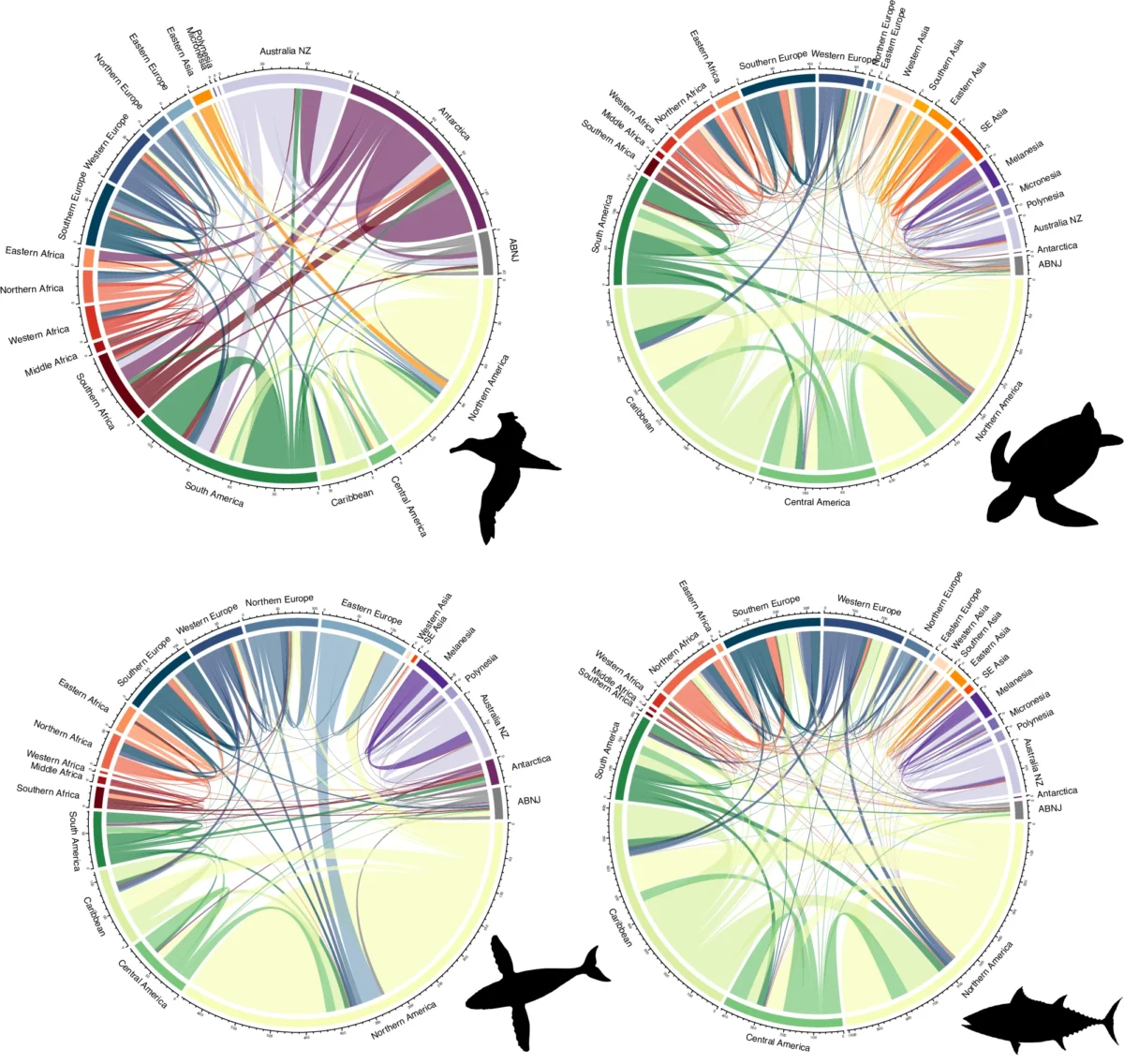

‘Our models show that no country can fully protect migratory species on its own,’ Dr Bentley explained. ‘To safeguard these species effectively, nations must work together.’

Centre director Associate Professor Daniel Dunn added that MiCO supports international efforts like the recent High Seas Treaty, aimed at protecting biodiversity beyond national waters.

‘MiCO’s freely available models have already been identified as a key asset to inform this treaty, helping policymakers understand how their countries and the biodiversity they are responsible for are connected to the high seas,’ Dr Dunn said.

The MiCO system also contributes to the Convention on Migratory Species’ global atlas of animal migration — a major step forward in the conservation world.

With over two-thirds of marine migratory species still unassessed, the team plans future expansions. ‘Our goal is to provide the most comprehensive global baseline of connectivity generated by marine migratory species possible, so conservation strategies are based on robust data,’ Dr Dunn said.

The MiCO database covers some of the ocean’s most iconic and wide-ranging travellers, providing conservationists with crucial data on their epic journeys. Among the best-known species mapped are the green sea turtle and loggerhead sea turtle, both famed for their remarkable migrations between tropical nesting beaches and distant feeding grounds. The leatherback sea turtle, the largest of all sea turtles, is also included, crossing entire ocean basins during its life cycle.

Several charismatic marine mammals feature prominently, including humpback whales, renowned for their acrobatic breaches and seasonal migrations between polar feeding grounds and tropical breeding sites, and blue whales, the largest animals ever to have lived on Earth. Sperm whales, known for their deep diving and social units, also make the list, adding to the breadth of species tracked.

Bird species like the Arctic tern, which completes the longest known annual migration from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back, and the striking northern gannet, famed for its plunge-diving prowess, highlight the remarkable aerial journeys mapped in the database. Key fish species such as the Atlantic bluefin tuna, a powerhouse of the ocean and a species under intense conservation focus, and the formidable great white shark, one of the ocean’s top predators, round out the impressive line-up.

Together, these species illustrate the extraordinary scale and diversity of marine migrations, underscoring why cross-border cooperation is essential to their survival. By visualising their movements, MiCO provides a foundation for stronger international conservation efforts.