From supporting the return of sea turtles to oceans, to witchhunts in West Africa, discover the world in our latest issue of Geographical

In our February 2026 issue, we look at how new technology is enabling injured sea turtles to regrow severely injured tissue and safely return to the ocean.

Also in our issue: head to Britain’s hedgerows where Stuart Butler discovers how this valuable network shapes wildlife, farming and the countryside today. Claire Thomas reveals how centuries-old superstitions continue to condemn women accused of witchcraft to exile in West Africa, while Tristan Kennedy unpacks the sleepy mountain village of Livigno that’s gearing up to host the Winter Olympics. Boštjan Videmšek reports on the ground at Cox’s Bazar, where more than a million Rohingya refugees remain trapped.

Our columnists bring an array of topics to the forefront to help you stay on top of the world: Tim Marshall discusses the Iranian crisis; Andrew Brooks reflects on class and care in Britain today; while Marco Magrini explores how artificial intelligence may be weakening our brains’ hard-worn capacity to learn and think.

Our digital edition is out now too, giving you access to all the stories in our latest issue, as well as our full archive dating back to 1935, with hundreds of magazines to explore. Digital access is available through the Geographical app, and you can now enable notifications to be alerted the moment the latest issue is live. And if you want to enjoy our beautifully designed and produced print magazine, we can post the next edition to you anywhere in the world. Join us and stay on top of the world!

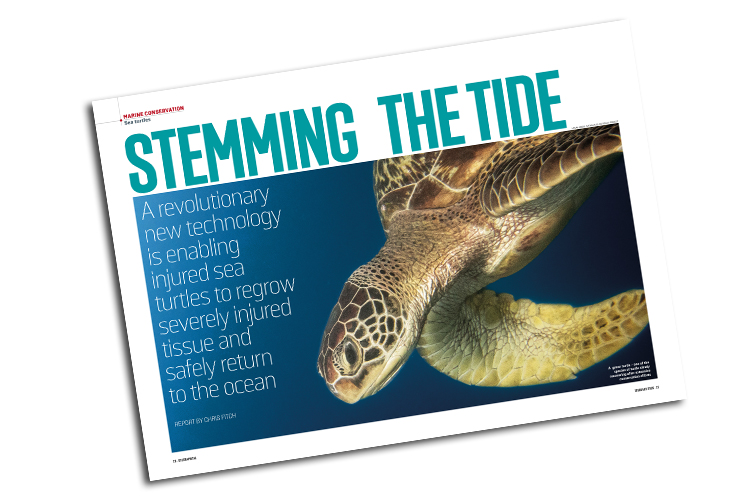

Stemming the tide

In the Maldives, where turquoise waters hide a growing crisis, discarded fishing nets drift in from across the Indian Ocean, ensnaring turtles in deadly traps. One of them was Nooru, an olive ridley rescued after becoming entangled in a ‘ghost net’. Despite surgery and months of care, severe lung injuries left her unable to dive, gas trapped inside her body slowly sealing her fate. Her story is heartbreakingly common in an archipelago that may have one of the world’s highest rates of turtle entanglement.

At the Marine Turtle Rescue Centre in the Baa Atoll, veterinary surgeon Michelle Chepng’eno Rop and her team fight daily to save turtles brought in with torn lungs, deep rope wounds and missing flippers. Some survive against the odds. Others, like Nooru, do not. Yet hope is growing. The Olive Ridley Project is pioneering cutting-edge treatments, including stem-cell therapy, allowing turtles to regenerate damaged tissue and, in some cases, avoid amputation altogether.

Now, with the opening of a purpose-built Sea Turtle Health Institute in the Maldives, conservationists believe they finally have the tools to transform survival rates. It will not solve the global crisis of abandoned fishing gear, but for the turtles drifting into Maldivian waters, a powerful new ally has arrived.

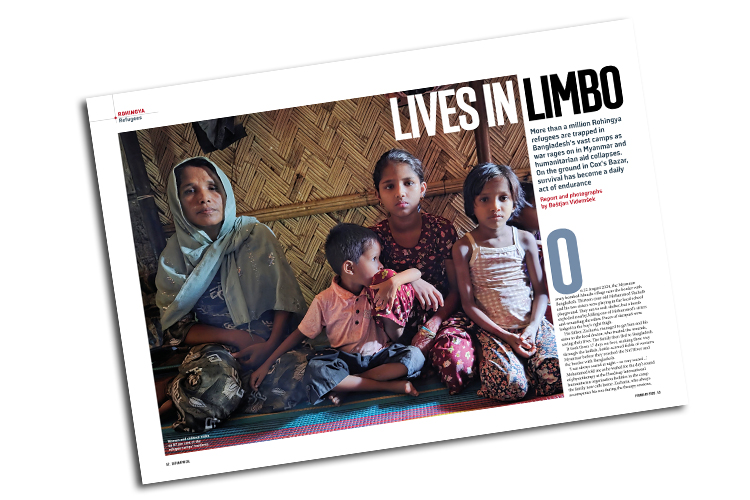

Lives in limbo

In Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar, the Rohingya crisis has hardened into a daily emergency. More than 1.2 million people now live in 33 packed camps, their lives shaped by persecution in Myanmar and the reality that, in Bangladesh, they still lack formal refugee status and the right to work. New arrivals keep coming as fighting intensifies in Rakhine state, while the camps themselves feel less like shelter than an open-air prison, ringed by barbed wire and watched by sentries.

Life here is a grind of heat, hunger and fear. Families crowd into bamboo-and-plastic huts where privacy, sanitation and safety barely exist. Cyclones and monsoon rains shred shelters; drought brings fires. Children make up the majority of residents, and malnutrition is rising as international budgets shrink and food rations face further cuts. Clinics measure fragile limbs and distribute therapeutic nutrition, trying to pull infants back from the brink.

As aid retreats, danger rushes in. Education centres close, gangs tighten their grip, and kidnappings and sexual violence spread through the alleys. Yet even in this bleakness, people cling to small lifelines — a functioning classroom, a community’s solidarity, a boy who smiles through trauma because school, for a few hours, feels safe.

Exercising our brains

Artificial intelligence promises extraordinary gains, from medical breakthroughs to cleaner energy. But beneath the excitement lies a quieter, more troubling risk. The human brain, uniquely shaped by years of effortful learning, develops through use. From infancy to adolescence, neural connections are strengthened by struggle and repetition, while unused pathways are pruned away. Intelligence, in other words, is built through hard work.

Generative AI threatens to short-circuit that process. As chatbots spread rapidly through schools and universities, students are increasingly outsourcing mental effort itself. History offers warnings: calculators dulled numeracy, GPS weakened spatial skills. AI could go further, undermining reasoning, memory and learning during the brain’s most vulnerable developmental stages.

Educators are already scrambling, abandoning written exams in favour of oral testing. Meanwhile, AI’s soaring energy demands raise further concerns. The greatest danger, however, is human. If a generation stops exercising its minds, we may inherit powerful tools — and too few people capable of truly understanding or using them.

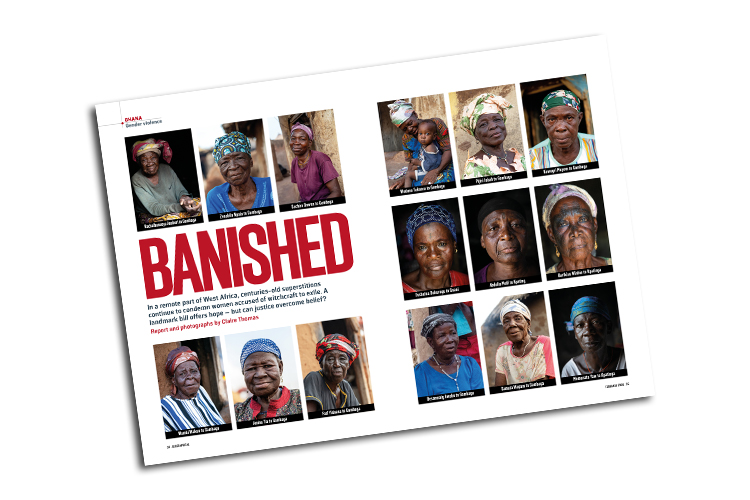

Banished from communities

In northern Ghana, belief in witchcraft is not a relic of folklore but a living force, one that continues to exile, silence and endanger women. Accusations — often sparked by illness, jealousy or grief — fall overwhelmingly on older, poor and widowed women, forcing many into isolated ‘witch camps’ where survival depends on charity and resilience. These settlements offer protection from mob violence, but little dignity or freedom.

Life in the camps is harsh: hunger, stigma and exploitation are common, while children who follow their mothers into exile inherit the label — and the punishment. Yet amid suffering, solidarity persists, sustained by churches, activists and women’s rights groups working quietly to support and reintegrate the accused.

Now, Ghana stands at a crossroads. A long-delayed Anti-Witchcraft Bill promises to criminalise accusations and dismantle the system that sustains exile. Whether it passes — and is enforced — will determine if superstition continues to dictate women’s lives, or if justice finally begins to catch up.

Britain’s ancient hedgerows

Britain’s hedgerows are so familiar we barely notice them — yet some are older than the Pyramids. On Dartmoor, Stuart Butler stumbled across the ‘reaves’: faint, ruler-straight ridges laid out by Bronze Age farmers 4,500 years ago, among the world’s oldest surviving hedges. And they’re not just archaeological curiosities. In parts of Cornwall, hedges more than 5,000 years old are still functioning as boundaries today.

Modern hedgerows are also lifelines for wildlife. In Devon alone there are about 53,000 kilometres, many centuries old, acting as homes, larders and highways for everything from hedgehogs and dormice to bats, beetles and butterflies. One 85-metre hedge surveyed by expert Robert Wolton held more than 2,000 visible species — with the true total likely far higher.

But these living ecosystems are under pressure. Post-war farming wiped out huge stretches, and today the threat is neglect or over-trimming. The solution is surprisingly physical: traditional hedge laying, a skilled craft now in short supply. If we want hedgerows to keep stitching together Britain’s wildlife — and its landscapes — we’ll need to relearn how to care for them.