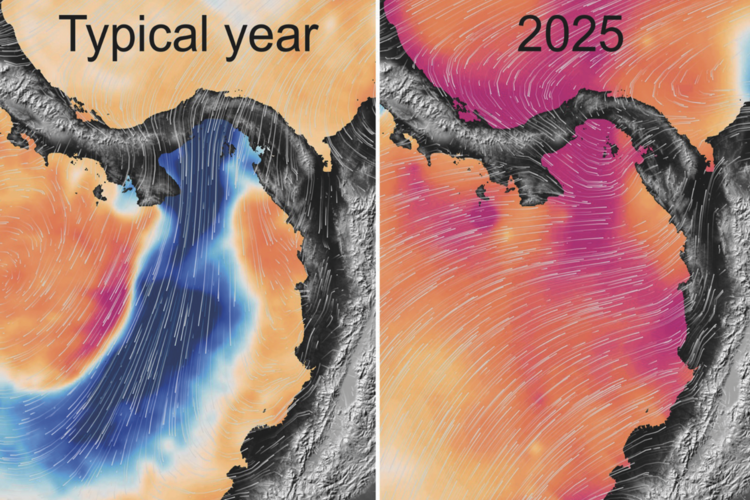

For the first time on record, the cold, nutrient- rich waters that sustain an entire ecosystem failed to surface in the Gulf of Panama

Every year, a plume of cold water rises to the surface in the Gulf of Panama, bringing with it a colossal surge of life – from phytoplankton to migratory sharks and whales.

Except that this year, it didn’t. When Aaron O’Dea, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, reported his team’s findings earlier this year, media headlines announced that Panama’s ocean upwelling had failed for the first time in 40 years. ‘What we actually said was that we only have 40 years’ worth of high-quality data and that, within those 40 years, we’ve never seen this happen,’ says O’Dea.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

In reality, scientists don’t know whether anything like this has happened before, or whether it will happen again. ‘We did go back and change the press release,’ O’Dea adds, ‘but by then it was too late.’

Ocean upwelling is a process where deeper, colder and nutrient- rich water rises to replace warmer, nutrient-depleted and less dense surface water that has been pushed away by prevailing winds. In the Gulf of Panama, it has been a remarkably predictable phenomenon – at least for the last 40 years that scientists have been monitoring it – always beginning by 20 January, lasting around 66 days, and dropping the surface temperature to 19°C or above.

O’Dea explains that this predictability is a direct result of the Earth’s orbital tilt, which causes an annual shift in the planet’s most intensely heated zone (the area where the sun shines most directly), creating the wandering band of low pressure known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). As hot air rises within the ITCZ, it generates a massive, dependable system of atmospheric circulation – the Hadley Cells – which in turn powers the trade winds that have been essential to global navigation since the age of sail, and which reliably drives the ocean upwelling in the Gulf of Panama.

We also know that this process has occurred in one form or another, for a very long time. The ecosystems that rely on this surge of available food have existed for hundreds of thousands of years. Scientists who have analysed

the isotopic compositions (chemical signatures that reflect temperature and salinity changes in the water) of two- to three-million-year-old shells from the Gulf of Panama have also found that they contain clear seasonal patterns, much like shells today.

‘In the tropics, where year-round temperatures are usually stable [unlike the strong seasonality at high latitudes], such seasonal cycles are only caused by upwelling,’ says O’Dea. ‘It’s unequivocal evidence going back about three million years.’

This year, temperatures in the Gulf of Panama didn’t start to change until 4 March. The drop, which only reached 23.3°C, lasted just 12 days.

O’Dea and his colleagues are fairly confident that less frequent (they reported a 74 per cent decrease) and shorter-lasting northerly winds caused the upwelling to fail, and suspect that these winds were the result of La Niña conditions. Without further research into both past and future events, they won’t be able to know whether this was an isolated incident or the start of a new trend. So far, anecdotal evidence suggests that this year’s conditions in the Gulf of Panama have had an impact on small pelagic fish – such as anchovy and herring, which are food for larger fish such as tuna – whose populations are strongly correlated to the strength of the upwelling.

‘These are fish that reproduce very quickly, grow very quickly and die very young,’ says O’Dea. ‘The turnover is really fast, so you see the effect immediately. And we’re hearing that the catch for this year has already dropped quite significantly.’

O’Dea hopes to extend existing records of Panama’s ocean upwelling beyond the last 40 years by looking at lower-quality (less reliable) older data and new climate models that can help reconstruct the past. He also plans to begin monitoring again in January, when the 2026 upwelling is due to start – a task that, due to the lack of researchers and funding in the region, could prove even more difficult.