By Charlotte Hall

For weeks, over a hundred cargo ships have been lining the waters and ports around the Panama Canal. After the driest two years in Panama’s 143 year record, the canal’s water levels are at a historic low point and the amount of vessels making the passage from one side of the Americas to the other has slowed to a trickle.

The long delays have propelled the region into the spotlight and as the world takes a sharp look at Panama’s changing weather patterns, it raises the question: is this the beginning of the end for the Panama Canal?

What is the Panama Canal and why does it matter?

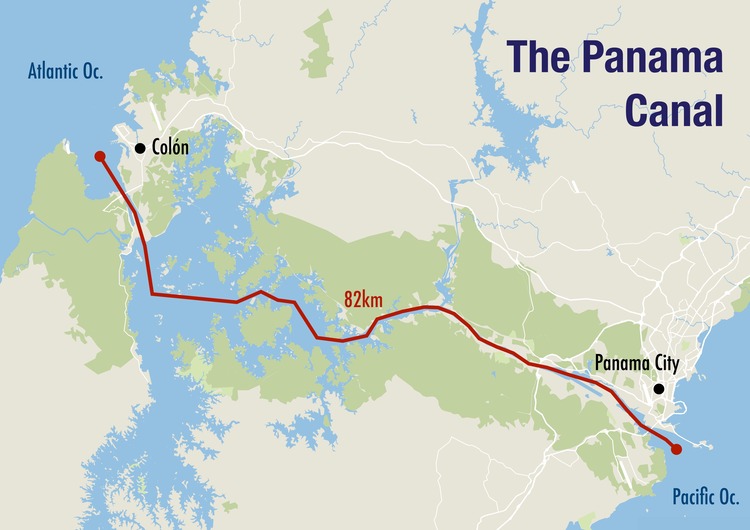

The Panama Canal is an artificial waterway that allows cargo ships to travel quickly between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean through a narrow strip of land called the Isthmus of Panama.

Without the 48 mile-long canal, the journey would take around two months, covering 9,200 miles of travel around the furthest point of South America, Cape Horn.

Six percent of global trade passes through Panama. It is an especially crucial thoroughfare for transport between the US and East Asia, on top of connecting the east and west coasts of the Americas and Europe with Australia.

Britannica goes so far as to describe the canal as “a barometer of world trade, rising in times of world economic prosperity and declining in times of recession.”

Serving more than 144 maritime routes, connecting 160 countries across 1,700 ports, according to the International Trade Administration, it is fair to say it plays a significant role in enabling globalised markets. Major products like grains, motor vehicles, coal and petroleum rely on the canal for efficient transit.

The history of the Panama Canal

The idea to create a gateway through the Panama isthmus started in the 16th century, when Nasco Nuñez de Balbao, explorer for the Spanish Empire, realised it would connect the two oceans. But at the time it was nothing more than a dream. The impossible terrain across the land, which encompassed landslide-prone mountains, tropical forests and unnavigable rivers, made even land crossings difficult.

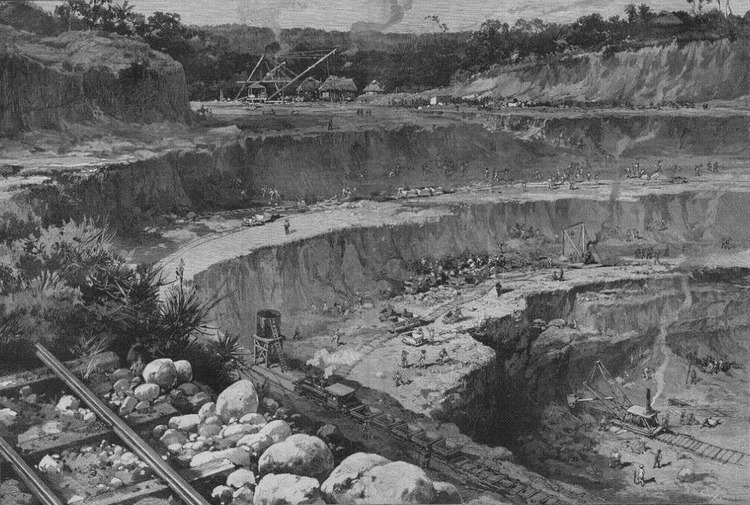

It was no surprise, then, that the first attempt to build the canal in 1881 failed. Undertaken by Ferdinand de Lesseps after his success with the Suez Canal, the first design suggested ploughing a way through the land by force to create a similar sea-level canal to the one in Egypt. After eight years of tragedy, in which landslides, malaria and yellow fever claimed the lives of over 20,000 French workers, the funding for the project was pulled and the construction abandoned.

Then in 1902, US president Teddy Roosevelt purchased the land in the canal zone from the French for $40 million. He sought a treaty with Colombia, which Panama was then a part of, to resume construction of the canal, but negotiations failed. Backed by the US, Panama declared independence a year later, and construction of the new lock-based canal system started soon after the creation of the Panama Canal Zone in 1904.

The modern construction of the canal was not without its dangers either, however. In 10 years of building, 5,600 workers were killed by further landslides and dynamite explosions.

When the Panama Canal opened in 1914, it was initially controlled by the US, but was passed to a joint Panama-US governance in 1979, and is now completely owned and run by Panama.

How does the canal work?

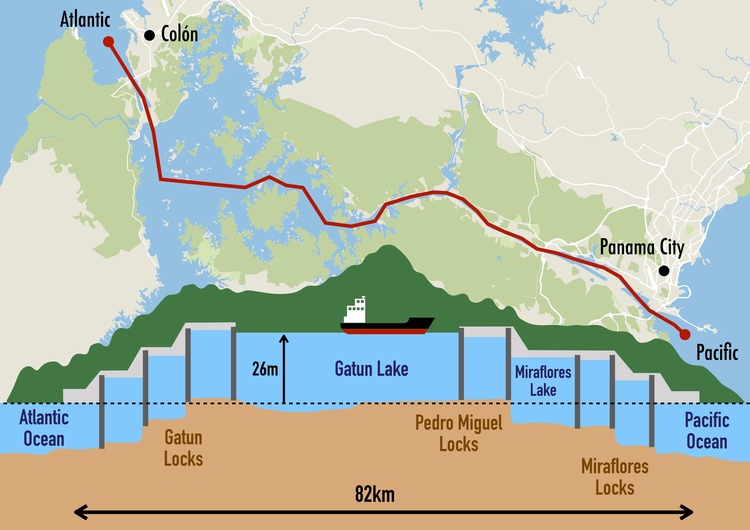

Panama Canal is unusual in that it works almost like a “water bridge”. Ships are hoisted 85 feet (26 metres) above sea-level using a series of locks and cross the land via Gatún Lake and a man-made river called the Culebra Cut.

Up until an expansion project in 2016, the canal had only two lanes and two sets of locks to transport shipping vessels. A third lane was then built to accommodate larger cargo ships.

The locks work using the power of the gravity flow of water between Gatún and two further reservoir lakes, Alajuela and Miraflores. The three locks across the canal each use four sets of gates, operated electrically, to raise or lower water levels to match the level of the next stage.

Ships have to be towed by electric locomotives and the whole journey from one side of the canal to the other takes around 10 hours.

Related links:

However, the mechanics are incredibly resource-intensive. Each crossing requires 200 million litres of water, enough to fill around 80 olympic swimming pools, according to the RTI. Most of the water is irretrievably lost in the process.

So far, this has rarely been a problem for Panama, which relies on the reservoir Lake Alajuela and freshwater top-ups from heavy rainfall during the wet season from May to December.

But for the past two years, Panama has experienced 30-50 percent less rainfall because of an El Niño weather pattern.

Thanks to the recent drought, Panama’s worst on record, water levels have dropped in both the canal and the reservoir. The canal authorities have had to introduce restrictions on the weight and size of vessels crossing through the canal, which are likely to continue for the next ten months.

Does Climate Change have anything to do with it?

El Niño is a naturally occurring weather oscillation. However, recent research by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation points to a strong link between the frequency of El Niño events and human-caused climate change.

At the same time, as global temperatures increase, extreme weather events like droughts are likely to become more prevalent in the region, with dry seasons starting unseasonably early and bringing record high temperatures.

Hot weather comes with the added risk of evaporation, aggravating low water levels.

Panama, and in particular the Canal, are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. That is despite contributing only 0.045% of global greenhouse gases, according to the Climate & Clean Air Coalition.

Since the canal is dependent on a freshwater supply, climate change could have a catastrophic impact on its future.

What would happen if the Panama Canal stopped working completely?

It is unlikely that the Panama Canal will cease operations entirely anytime soon. However, the drought has shown that necessary restrictions and limitations on cargo weight can cause significant – and costly – delays.

This can have knock-on effects on supply lines. The vulnerability of the globalised economic system was highlighted during the pandemic, when reduced international air travel resulted in shortages and shortfalls in some materials and products. But since over 80 percent of goods are carried by sea, according to a UN body, climate disruptions to maritime trade could be far more disruptive.

Especially for the US, who see roughly $270 billion worth of their cargo flow through the canal, finding alternative routes would present a huge cost in money and time.

For Panama, the result would be disastrous. The majority of the country’s economy is contingent on the canal, which feeds its booming services sector.

In addition to economic impacts, finding new routes to bypass the canal would likely result in longer, more carbon-intensive routes, adding further fuel to the fire.

Can the Panama Canal adapt?

One solution to that bleak prognosis is adaptation. In May 2023, Panama announced it was strengthening its efforts to design a Climate Change Adaptation plan. The plan will include suggestions for sustainable water management.

When the new lock was built for the 2016 canal expansion, Panama trialled a water recycling system that saves around 60 percent of the water used for raising and lowering the ships. The project was a success.

Yet the two older locks still lose the majority of the water used for their operation. It would require a tremendous overhaul in order to fix the older locks.