Global shipping still relies on polluting fuels and many fear that its promises to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 are little more than hot air

By

Most people, if you quizzed them, probably wouldn’t know how much of all global trade is done by sea,’ says Tim Smyth. It’s one of several reasons, he believes, that the pollution and carbon emissions from shipping garner much less attention than those from road transport and other industries. ‘It’s over the horizon, out of sight and out of mind.’

In recent years, various attempts have been made to clean up the sector, including the introduction (in 2020) of fuel regulations to reduce air pollution. Prior to this, says Smyth, who is head of science for marine biogeochemistry and observations at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, ships could burn ‘pretty much what they liked’ for fuel. But despite the new rules, shipping remains a dirty business. It’s responsible for a significant portion of the world’s nitrogen oxide pollution (estimated at between 18 and 30 per cent) and accounts for three per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions, a figure that could rise to 17 per cent by 2050 if left unchecked.

In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) announced its commitment to reducing carbon emissions from all ships by 40 per cent by 2030, a goal seen by many to be entirely incompatible with global efforts to hit net zero by 2050. Several environmental organisations have since criticised the IMO for stalling on urgent climate action. Moreover, in April this year, management consultancy firm McKinsey & Company produced a report revealing that more than a third of sea freight companies have yet to take any significant action regarding a switch to greener fuels. Nor did they know what kind of fuel their fleet might run on in the future.

Today, the international shipping industry is the main mode of transport for around 90 per cent of world trade. It’s powered almost entirely by fossil fuels. Studies show that alternative technologies and zero-emission fuels – including electrofuels such as hydrogen, ammonia and methanol – have the potential to significantly reduce the industry’s carbon footprint and thus require urgent implementation. There’s just one catch: they don’t exist yet.

‘There are some really promising proofs-of-concept, such as electric trucks for logistics, and there are some hybrid electric vessels,’ says Piotr Konopka, senior manager for energy and decarbonisation programmes at DP World. ‘But they are nowhere near being commercially available off-the-shelf.’

Konopka, who is also involved in the work of the Maersk McKinney Center for Zero Carbon Shipping, a not-for-profit looking for solutions to decarbonising the world’s 100,000 commercial vessels, is all too aware of the challenges ahead. ‘It is a hard-to-abate sector,’ he says, ‘and a lot of the sectors that work within the shipping industry, such as trucking, also consume a lot of fuel and use a lot of incumbent technology that doesn’t necessarily have any alternatives.’

Even if the technology were available, it would only represent one piece of the puzzle. ‘The infrastructure for that technology or fuel is going to take time to develop. And an even bigger challenge is going to be whether that methanol or ammonia fuel is green, which touches on other industries such as renewable electricity. Do we even have enough renewable electricity in the world to be able to generate these fuels? It’s a complex supply chain that requires collaboration across the industry. It’s not something that one company can solve by itself.’

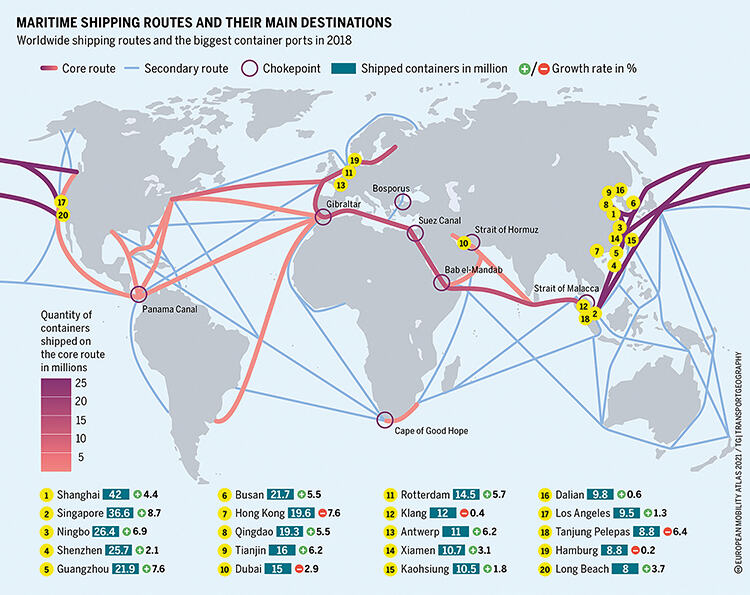

One way that the industry is hoping to accelerate decarbonisation is through the implementation of green shipping corridors – specific trade routes between major port hubs where zero-emission solutions are supported with the necessary infrastructure and logistics. Currently, plans are in development for some of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, including one corridor between Los Angeles and Shanghai (the trans-Pacific shipping lane moves more than 20 per cent of the world’s shipping containers) and another between Rotterdam and Singapore.

Green shipping corridors have been promoted as a ‘catalyst for change on a global scale’; however, they will still require a phased transition to low, ultra-low and finally zero-emission fuels by 2030. According to Konopka, there are some simple behavioural changes that can help cut down on fuel used in the meantime, from the regular maintenance and reduced idling of port equipment to the implementation of weather routing that helps vessels avoid rougher, more fuel-intensive stretches of water. ‘Of course, efficiency is unlikely to ever reduce emissions by more than five or ten per cent, but it’s definitely a low-hanging fruit,’ he says.

According to McKinsey & Company, 80 per cent of shipping companies think that regulatory change is needed to accelerate the transition to greener fuels. ‘Regulation is 100 per cent the key driver for us,’ agrees Konopka. In July, the IMO’s environment committee met to discuss whether more ambitious emissions targets were needed – an event dubbed the most important climate meeting of the year. ‘This is the last moment for the IMO to act decisively to eliminate shipping emissions as the pace of climate change and its catastrophic impacts continues to accelerate, says Delaine McCullough, shipping emissions policy manager at environmental NGO Ocean Conservancy. ‘We need countries to demand that the IMO sets strong emission-reduction goals of 50 per cent by 2030 and 100 per cent by 2040 and to take action at home if the IMO fails to do the right thing.’