El Niño is a term used to describe one of the biggest climate fluctuations on Earth, an event that can contribute to cyclones, disease and famine

By Susanna Gough

What is El Niño?

Formally known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), El Niño is an agent of chaos in the Pacific Ocean weather cycle. It is a regularly occurring phenomenon, typically lasting nine to twelve months, in which air pressures change, causing the trade winds that traverse westwards across the Pacific Ocean to slow down or reverse. This meekly named ‘Little Boy’ is a formidable driver of climate variation, dictating weather patterns across the globe with consistently catastrophic consequences for ecosystems, agriculture, and the global economy.

How Does El Niño Happen?

Under neutral conditions, trade winds carry warm surface waters over the Pacific to southeast Asia and Indonesia, where moist air rises and causes high rainfall. Meanwhile, cold water rises from Antarctic waters, in a process known as ‘upwelling’. This circuit produces cooler, drier conditions on the South American seaboard.

Under El Niño conditions, however, surface waters remain warm on the South American side, causing higher precipitation. Warmer temperatures reduce upwelling of cold water, perpetuating a cycle of warming. This concurrently causes hot, dry conditions on the Asian side.

Related stories – articles

Atmospheric air currents are also altered. In the Hadley circulation, warm air rises near the equator and descends at the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. In an El Niño event, however, the circulation is strengthened, affecting jet streams which, as the US National Weather Service puts it, ‘steer storms around the world’.

What can we expect this time?

So, what can we expect this time? In western South America, northeast Africa, and the southern US, rainfall and flooding are likely to increase. In Brazil, Australia, India, and the western US, dryer, hotter conditions are expected. The subtropical jet stream that gives northern Europe mild, wet winters will be pushed south, relaying those moist conditions to southern Europe, and threatening a dry, cold winter for the northern nations. The incidence of tropical cyclones in the western Pacific is also forecasted to increase, alongside bushfires in dryer regions.

This is only speculation. El Niño is a fickle and volatile force and wreaks havoc in different ways every time.

How is an El Niño event declared?

An El Niño is declared when surface temperatures in the western Pacific remain 0.5°C above the thirty-year average for three months or more. Meteorologists predict ENSO events through a variety of monitoring techniques. Satellites are used to monitor wind and rainfall patterns, buoys to measure sea surface temperatures, and radio technology to measure air temperature, humidity, and pressure.

El Niño was documented long before this sophisticated weather technology was invented. South American fishermen in the seventeenth century coined the term. These proto-meteorologists noticed higher sea temperatures and rainfall in certain winter seasons, and thus named the phenomenon ‘El Niño de Navidad’, or ‘Christ’s Child’ in English.

What happened in previous El Niño years?

The most recent, large El Niño events occurred in 2015-16, and in 1997-8.

Natural disasters and famine

In 2016, sixteen tropical cyclones were recorded in the central Pacific basin, an almost fourfold increase from the average rate. There was also severe drought in ten Caribbean nations, with emergency water rationing being necessary in St Lucia and Puerto Rico. In Ethiopia, eight million people required food aid as drought caused widespread crop failure.

Disease

El Niño routinely causes higher incidence of disease.

In Indonesia in 2015-6, low rainfall encouraged mosquitoes to move to cities where they could find water sources that they require for breeding. As a result, more people contracted dengue fever from mosquito bites. In the southern US, increased rainfall caused more vegetation to grow, giving rodents more food to eat. This increased the number of rodents carrying hantavirus and plague, increasing their incidence among humans. In Tanzania, cholera levels increased because high rainfall flooded sewage systems, contaminating drinking water sources.

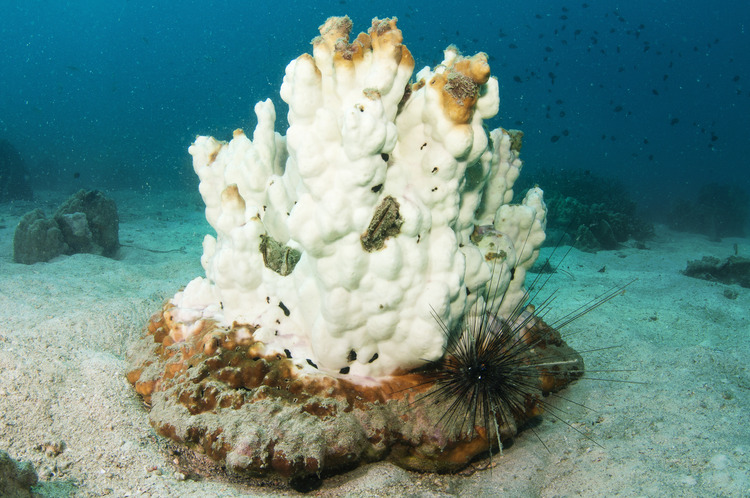

Coral bleaching

Coral bleaching occurs when high temperatures expel colourful zooxanthellae algae from their coral dwellings. This algae produces vital nutrients, and when it is absent for long periods, the coral cannot survive. The Reef Resilience network found that after the 1997-8 El Niño, between seventy and eighty per cent of corals in Indo-pacific reefs had been bleached. When studying a 1,000km stretch of 524 coral reefs off the coast of Australia in 2016, the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies found that only four had not been bleached. Read more about threats to coral reefs, and how we can help, here.

Economic Effects

The 1997-8 El Niño event is estimated by the World Bank to have cost governments $45 billion. Another study in the academic journal Science found that the same event led to $5.7 trillion in income losses worldwide. Furthermore, these events affect countries in the global south disproportionately. Researchers at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire found that while the US GDP was three per cent lower five years after both the 1982-3 and 1997-8 El Niño events, the GDP of coastal tropical countries suffered a consistent 10 per cent drop.

Countries are already making financial preparations for the coming El Niño. India is delaying sugar exports until next season. In the Philippines, a special government taskforce has been created to handle the effects of El Niño, and in Peru, $1.06 billion has already been set aside to deal with the impact.