A 35-year study of deep-sea vents has uncovered temperature clues that may warn of future eruptions

By

The East Pacific Rise (EPR) is a massive mid-ocean ridge that runs more than 16,000 kilometres from near the Gulf of California into the southeastern Pacific Ocean.

It’s the fastest-spreading ridge system on Earth, pulling apart at rates reaching 150 millimetres per year and lifting the seafloor 1,800 metres above the abyssal plains in the process.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

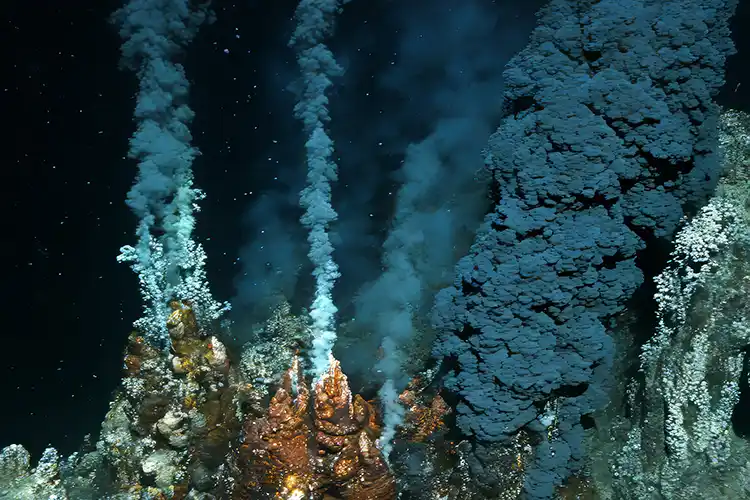

All this rapid tectonic activity makes the EPR a very volcanically active place, and it’s home to some of the world’s best- studied hydrothermal vents – or ‘black smokers’, as they’re often called – which release a continuous stream of chemical- rich water that can reach temperatures above 350°C.

‘Mid-ocean ridges are where much of Earth’s internal thermal energy is transferred to the ocean,’ says Dan Fornari, a marine geologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the USA. ‘Until now, we lacked a direct way to link what we can measure at the seafloor to what’s happening deep below, where magma accumulates and drives eruptions.’ A new study shows that the two are closely connected.

The research team, led by Thibaut Barreyre, a marine geophysicist at the French National Centre for Scientific

Research, set to work assembling data collected from the vents over the last 35 years to see what it might reveal about the magmatic and tectonic processes that occur miles beneath the seafloor.

They found that vent temperatures at the EPR rose steadily from around 350°C to nearly 390°C in the years preceding two known eruptions – one that lasted from 1991 to 1992 and another from 2005 to 2006. Following the second event, temperatures dropped back to about 350°C but have been climbing ever since – likely driven by rising pressure in the oceanic crust, itself caused by the gradual increase of magma located roughly 1.5 kilometres beneath the seafloor. It’s a clear signal, the researchers say, that could help

us anticipate eruptions before they occur – which could prove beneficial for mitigating hazards to underwater infrastructure such as fibre-optic cables.

The team confirmed an eruption took place this year, one they had previously forecast based on hydrothermal data collected from the vents. ‘This is an extraordinary step forward in submarine geophysics,’ says Fornari. ‘Hydrothermal vents are not just biological oases – they are windows into the dynamic processes that shape our planet.’