From the cascading devastation inflicted by Trump aid cuts, to a North Pole expedition, stay on top of the world with the latest issue of Geographical

In our January 2026 issue, we unpack Trump 2.0 in our special report, revealing the stark impacts that his administration has had on the world in the last twelve months. From aid cuts to vital health work in Lesotho to imposed tariffs, fleeing talent and allies snubbed, Geographical delves into the year the world changed.

Also in our issue: head to the Atacama, where Shafiq Meghji journeys through Chile’s far north to reveal how the ‘lifeless’ desert shaped global agriculture, redrew borders and left a political legacy that continues to resonate. Doug Specht surveys a blank square kilometre of farmland on the Ordnance Survey to find a landscape rich with life, memory and meaning, while Tristan Kennedy gives his top tips for wildlife spotting in winter.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

Our columnists bring an array of topics to the forefront to help you stay on top of the world: Tim Marshall discusses the shift away from liberal internationalism; Andrew Brooks talks about the importance of Geography as a degree; while Marco Magrini explores how technology is pushing us toward peak emissions faster than politics ever could.

Our digital edition is out now too, giving you access to all the stories in our latest issue, as well as our full archive dating back to 1935, with hundreds of magazines to explore. Digital access is available through the Geographical app, and you can now enable notifications to be alerted the moment the latest issue is live. And if you want to enjoy our beautifully designed and produced print magazine, we can post the next edition to you anywhere in the world. Join us and stay on top of the world!

The year that changed the world

A year ago, many expected a second Trump presidency to echo the first: loud, chaotic and ultimately constrained. Instead, the opening year of Trump 2.0 has redrawn the map of US power with startling speed. This has been a year of acceleration — of institutions hollowed out, alliances loosened and long-standing safeguards pushed aside.

Across Washington, the machinery of science and regulation has been stripped back. Agencies that track storms, heat, disease and pollution have lost thousands of staff, while research budgets have been slashed and rules dismantled. Supporters hail a war on bureaucracy. Critics see something more profound: the deliberate unpicking of systems designed to protect people, places and public health.

The retreat has not stopped at America’s borders. The US has stepped away from global climate commitments, withdrawn from the World Health Organization and helped sink efforts to curb emissions from shipping — leaving international cooperation weaker at a moment of rising planetary risk.

From deadly floods to record heat, the consequences are already visible. Scientists warn that what has been lost cannot simply be rebuilt. As expertise drains away, the question now is not whether this year has changed the world, but how long its effects will last — and who will pay the price.

The cuts that cost lives

When the United States froze all foreign aid, the consequences in Lesotho were not gradual or abstract. They were immediate. In mountain villages where healthcare already arrives on horseback, HIV support networks collapsed almost overnight, leaving clinics silent and patients suddenly alone.

This story unfolds far from Washington, in a country where nearly one in five adults lives with HIV and decades of progress have depended on fragile webs of community care. Health workers who once tracked patients across valleys and ridges were sent home. Outreach programmes stalled, then vanished. Those who missed appointments were no longer followed. Some were never found again.

Lesotho had been edging closer to the UN’s 95-95-95 targets, a rare success story built slowly, village by village. The aid freeze reversed that momentum with brutal speed. In the highlands, where road access is rare and poverty widespread, patients now travel hours for medication — if they travel at all. Others default, arrive too late, or disappear from the system entirely.

Beyond the clinics, the shock rippled outward. Feeding schemes closed. Support groups disbanded. Communities that had learned to live with HIV were pushed back towards fear and uncertainty.

This is not a story about policy in principle. It is about what happens when a lifeline is cut — and how quickly hard-won gains can unravel.

Courthouse drama

Across the United States, immigration courts have become front lines. What were once procedural spaces are now sites of sudden enforcement, where the boundary between due process and detention has all but disappeared.

In federal courthouses from Manhattan to the Midwest, armed immigration officers wait in corridors and by elevators, detaining people immediately after their hearings — even when judges have granted them permission to remain while cases continue. Many of those taken away have followed every rule, attended every appointment and carry no criminal record.

Beyond the walls, the consequences ripple outward. Journalists documenting arrests have been injured. Press-freedom groups have raised alarms. Families from Venezuela, Ecuador and El Salvador describe partners vanishing into detention without warning, children left without carers, and legal cases stretched across years.

Court, once a place of protection, now offers no guarantee of safety — only another threshold of uncertainty.

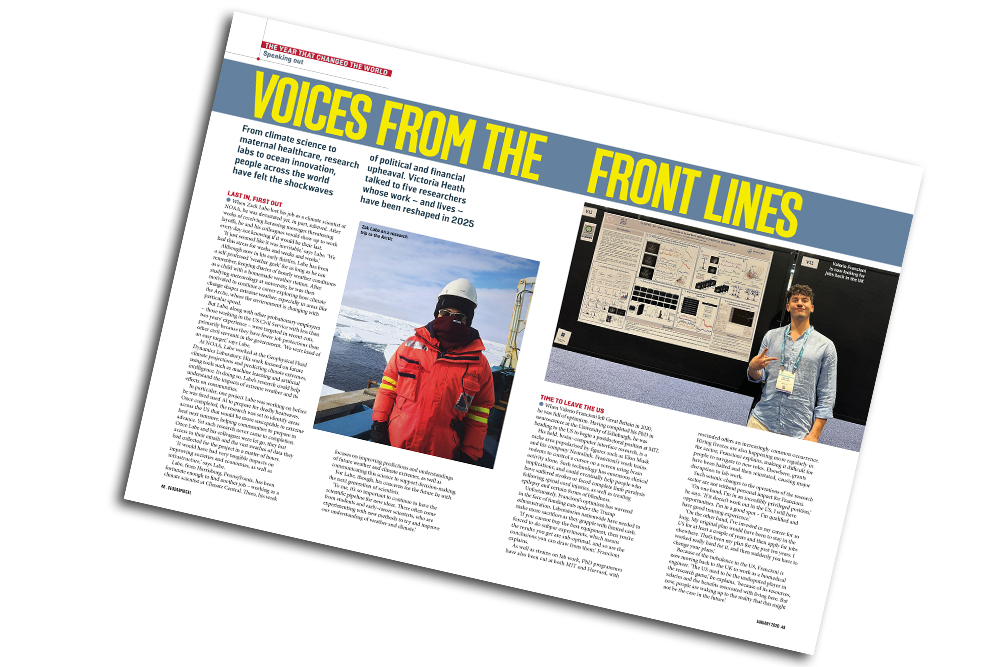

Voices from the front lines

From climate science to maternal health, from Arctic fieldwork to ocean innovation, the shockwaves of 2025 have travelled far beyond Washington. This has been a year when research careers were abruptly derailed, long-term projects abandoned and global progress put on pause.

In the United States, early-career scientists were often the first to go. At NOAA, climate researchers working on extreme heat, Arctic change and future weather risk lost their jobs with little warning, severed overnight from the data and tools they had spent years building. Elsewhere, funding cuts rippled through universities and laboratories, forcing hiring freezes, rescinded PhD offers and stalled experiments. For some, the upheaval has prompted a reassessment of whether the US remains a viable place to build a scientific career at all.

On top of the world

Almost a century after the first undisputed journey to the North Pole, it remains a place that feels both unreachable and irresistible. In September 2025, Geographical’s Digital Editor, Victoria Heath, stood there herself — more than 1,100 kilometres from the nearest land, surrounded by nothing but ice, sky and silence.

Her journey, aboard the polar icebreaker Le Commandant Charcot, took her to one of the least-visited places on Earth. Fewer than 1,000 people reach the North Pole each year, and fewer still do so with the chance to step out onto the drifting pack ice. Wrapped in orange parkas, passengers disembarked into a landscape so featureless it was almost disorientating — a horizon of pure white, where ice and sky merge and direction quickly loses meaning.

Yet this was not simply a moment of polar wonder. Heath was visiting a region undergoing profound transformation. The Arctic is warming four times faster than the global average, its sea ice shrinking by more than 12 per cent each decade. Scientists travelling alongside passengers were drilling ice cores, sampling deep ocean water and documenting changes unfolding in real time.

From historic exploration to modern science — and now tourism — the Arctic has long drawn people northwards. What Heath witnessed was a place still capable of awe, but increasingly shaped by forces far beyond its frozen horizon.

Moving into a new era

New eras rarely arrive with a single, decisive break. More often, they emerge through gradual shifts in power, priorities and assumptions. The post-Cold War world — dominated by a confident, unchallenged United States — has been fading for years. Donald Trump’s return to the White House has accelerated its end.

For decades after the Second World War, the US pursued strategic restraint, building alliances and promoting shared values as the foundation of global stability. That approach helped sustain a long period without direct conflict between major powers. Today, it is being abandoned. Trump 2.0 rejects the idea that American prosperity depends on cooperation, favouring tariffs, military strength and transactional relationships instead.

Alliances are being recalibrated, human rights sidelined and climate commitments discarded. The language of shared values has given way to spheres of influence and hard power.

There are echoes of earlier American isolationism, but this is not a return to the past. As power shifts towards the Indo-Pacific and climate and technology reshape the world, this marks the opening of a new, uncertain era.

An abundance of space

At first glance, SE 830 220 barely exists. On an Ordnance Survey map of the East Riding of Yorkshire, this one-kilometre grid square is almost blank — no footpaths, no buildings, no landmarks to guide the eye. It is, on paper, one of the least-detailed places in Britain.

On the ground, it tells a very different story. These low-lying fields beside the River Ouse are shaped by centuries of labour: drainage dykes cut to hold back water, hedgerows alive with birds, soils worked and reworked by generations who know every field by name. Wildlife spills across the landscape — lapwings, marsh harriers, hares and wintering geese — part of a wider ecological system linked to the wetlands of nearby Blacktoft Sands.

What the map records is geometry. What it misses is memory, effort and life itself. SE 830 220 reminds us that landscapes are not defined by what is labelled, but by what is lived, tended and remembered — and that some of the fullest places remain, deliberately or not, blank.