As governments from the Gulf to Beijing quietly buy up farmland around the world, a silent shift in global power is underway – one that few have noticed, but all will feel

By James Rose

When people think of wealthy Middle Eastern countries investing abroad, they often picture ownership of prestigious football clubs or luxury real estate in London’s most exclusive neighbourhoods. But in recent years, these nations have been quietly channelling billions into a far less glamorous – and far more strategic – sector: agriculture.

From Serbia to Brazil, and Australia to India, Middle Eastern governments have been acquiring farms and food-processing operations around the globe.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

Consider Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, SALIC, which says it manages about US$7billion in agricultural assets across seven countries on five continents – part of a total portfolio worth around US$8billion. These are not just financial ventures; they sit at the intersection of commerce, national security and geopolitics. In a world where food security is increasingly seen as a critical vulnerability, controlling food production has become a strategic priority.

This shift reflects a broader global trend – one that economist and writer Gillian Tett has described as ‘the new age of geoeconomics’. After decades of globalisation and free trade, nations are beginning to view commerce not merely as a path to prosperity, but as both a national security concern and a tool of statecraft.

From securing access to essential raw materials to reshoring the production of critical components, countries are adjusting to a new geopolitical reality. For many emerging powers – particularly those in the Middle East – the rationale for agricultural investment is clear. In an increasingly unstable world, dependence on volatile global supply chains and commodity markets carries significant risk.

The Covid-19 pandemic underscored the fragility of these supply chains. When goods are scarce, they go to the highest bidder – if they’re available at all. For heavily import-dependent nations such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which import roughly 80 per cent and more than 90 per cent of their food, respectively, supply disruptions pose not just logistical problems but existential threats. The strategic logic becomes obvious: why rely on buying food grown on foreign farms when you can simply buy the farms directly?

Few countries have pursued this strategy more energetically than the United Arab Emirates. After the 2007–08 food crisis, the UAE began allocating substantial resources to securing its food supply. In 2019, it launched the National Food Security Strategy 2051, which set out a plan ‘to make the UAE the world’s best in the Global Food Security Index by 2051’. This was to be achieved through a multi-pronged approach – investing in technology to boost domestic production and reduce waste, and – just as importantly – investing directly in foreign food production to ‘diversify food sources’.

The UAE has employed a variety of methods to implement this strategy. In 2022, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund ADQ acquired a majority stake in Unifrutti, a global fruit company managing more than 14,000 hectares of farmland – mostly in Latin America – and producing around 600,000– 700,000 tonnes of fruit annually. Under its new Emirati owners, Unifrutti has expanded further, consolidating control over Latin American fruit production.

At the same time, the Emirates-based conglomerate Al Dahra – also partly owned by ADQ – has become heavily involved. In 2018, it took over the Brăila Island concession in Romania under a long-term lease running to 2032, which it describes as Europe’s largest consolidated farm (around 55,000–56,000 hectares).

At roughly the size of the Isle of Man, the farm is a powerful symbol of Emirati agricultural ambition. Al Dahra also controls 18,000 hectares in Serbia and another 10,000 in Spain, along with other holdings. The company says it operates 30-plus processing plants worldwide and runs Etihad Mills in Fujairah, where silos can store up to 300,000 tonnes of grain.

The full scope of the UAE’s agricultural investments is difficult to measure. Many transactions receive little media coverage, and the often-opaque ties between state entities and nominally private firms blur the lines between commerce and strategy. Still, according to the Spanish non-profit GRAIN, by 2024 ‘the Emirates have amassed some 960,000 hectares of farms overseas’. If accurate, that would exceed the size of Cyprus.

The strategy extends beyond farmland. UAE-linked companies are investing heavily in the infrastructure required to process, store and transport food. Hundreds of millions of dollars have gone into building silos, logistics hubs and ports. DP World, the Dubai-based shipping giant, now operates more than 60 ports globally and has committed more than €130 million to upgrade several in Romania, including Constanța – a key hub for grain exports.

This infrastructure creates a seamless, vertically integrated supply chain – one that ensures food can be efficiently exported from the farms directly back to the UAE, bypassing the unpredictability of global markets.

Other Gulf states have also adopted similar investment strategies. In 2008, Qatar established Hassad Food, a subsidiary of its sovereign wealth fund, to diversify its food sources. Today, the company maintains agricultural investments in multiple countries across Asia, Africa and Europe.

China, too, has been expanding its agricultural reach. With the growth of its middle class, demand for food – particularly meat – has risen sharply, increasing the need for feed crops such as soybeans and maize. To ensure a stable supply for its domestic livestock sector, China is turning to new producers and diversifying away from the USA and Brazil.

Much of this has been incorporated into the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s sweeping global infrastructure programme. The goal is not just trade – it’s influence. In Africa, China has targeted countries such as Benin, Tanzania and Ethiopia as future soybean hubs, investing heavily in local production. The transformation has been striking. In 2019 Tanzania exported just US$7.5million worth of soybeans; by 2023, that figure had grown to US$92.7million, with China the largest buyer.

A more contentious example came in 2013, when reports claimed that China had agreed a long-term lease of up to three million hectares of farmland in Ukraine – equivalent to about ten per cent of the country’s total arable land.

However, the Ukrainian partner company KSG Agro later denied that such a deal had been finalised, and no evidence suggests it was ever implemented. Even so, the story reflected Beijing’s growing appetite for agricultural self-sufficiency. Saudi Arabia’s SALIC has also leased nearly 200,000 hectares in Ukraine, underlining the region’s enduring appeal as the world’s breadbasket.

It’s important to note that Western companies, too, have been acquiring farmland and agricultural firms around the world. What sets these Middle Eastern and Chinese efforts apart is the degree of strategic coordination behind them. The transactions are not merely motivated by profit – they form part of coherent national strategies.

Where media coverage exists, it often frames such moves as examples of ‘land grabbing’ or even neo-colonialism. These criticisms are not always unfounded – but nor are they entirely fair. Many acquisitions have brought in capital and technology, improving yields and creating jobs.

To understand what’s driving these investments, one must look at the growing vulnerabilities of the global food system. In the 1960s and 1970s, the world underwent a ‘Green Revolution’. Innovations such as dwarf wheat led to huge increases in yields, preventing widespread famine. So transformative were these developments that Norman Borlaug, one of the key figures behind them, was awarded the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize.

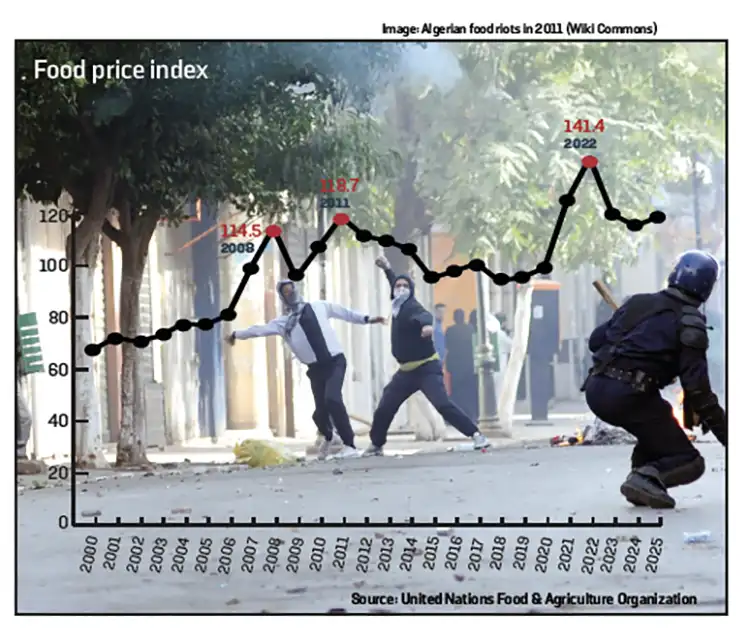

The result was a global food surplus, and from the 1970s through the early 2000s, food prices remained relatively low and stable. But by the mid-2000s, this began to change. Droughts, rising oil prices (which raise fertiliser and transport costs) and shrinking reserves triggered steep price increases. Financial speculation by hedge funds and traders added fuel to the fire. Between January 2006 and March 2008, wheat prices tripled – from US$167 to US$481 per tonne.

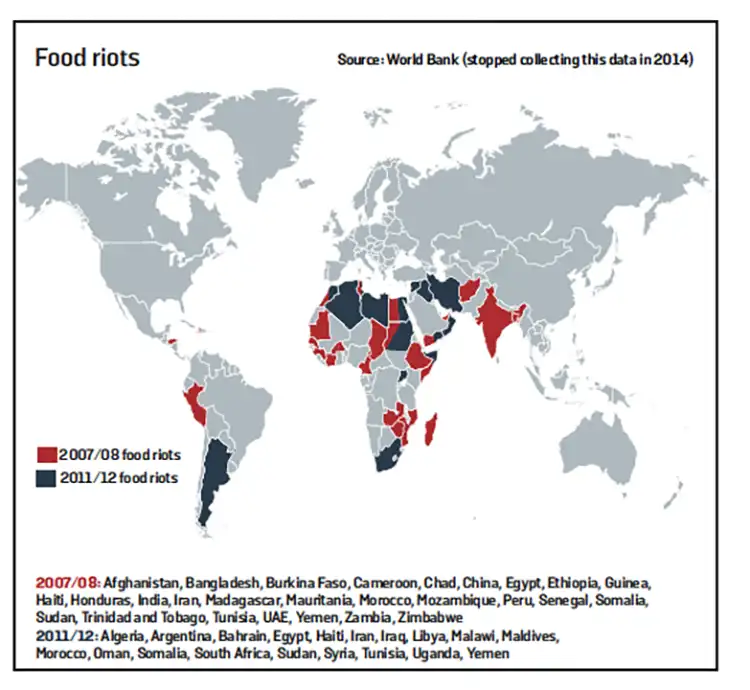

The consequences were severe. Millions were pushed into poverty, and food riots erupted around the world. In Yemen, bread prices doubled in four months, sparking protests that left at least a dozen dead. In Cameroon, unrest led to 24 deaths and more than 1,500 arrests. According to World Bank data, at least 25 countries experienced major food-related unrest in 2008 alone – and some experts believe the true number was higher.

Since then, the world has endured two more food crises. In 2010, droughts and high oil prices once again sent food prices soaring. By 2012, a scorching summer in Europe and the USA pushed corn and soybean prices to record highs. These spikes again plunged millions into poverty. Food prices also played

a key role in the Arab Spring, which brought down governments in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. For many who witnessed these crises, the conclusion was obvious: if you want to survive, keep your population fed.

Then, in 2022, came another shock – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war disrupted grain exports from both countries. Combined with lingering supply-chain issues from Covid-19 and extreme weather events the previous year, global food prices hit record highs. Again, governments drew the same lesson: global supply chains are volatile, and it’s better to have your own.

Worryingly, several long-term trends suggest that future crises may become more frequent and severe. As the world grows wealthier and more urbanised, meat consumption rises. China’s poultry consumption per capita has tripled over the past 30 years, while pork consumption has risen by more than 60 per cent, according to the OECD. Since producing one kilogram of meat requires several kilograms of grain or soy, this puts immense pressure on feed markets.

At the same time, climate change is already disrupting agriculture, with extreme weather – droughts, floods and heatwaves – occurring more often. While some colder regions, such as Russia and Canada, may benefit in the medium term, others – such as the American Midwest – could face devastating crop losses.

A study published in Nature found that every 1°C rise in global temperature could reduce average food availability by about 120 calories per person per day. As Stanford economist Solomon Hsiang put it: ‘If the climate warms by three degrees, that’s basically like everyone on the planet giving up breakfast.’

Meanwhile, the global population continues to grow. According to the UN’s 2024 World Population Prospects, it now exceeds eight billion and is projected to reach 9.6–9.7 billion by 2050. Much of this growth will occur in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia such as Pakistan – areas especially vulnerable to climate impacts. This could trap hundreds of millions in a cycle of poverty and hunger.

These new global food supply chains are not merely economic; they are reshaping the geopolitical landscape. Once a country has invested heavily in additional 162,000 hectares in the northeast of the country.

Since the outbreak of violence, reports suggest that the UAE has covertly supported the Rapid Support Forces, the Sudanese paramilitary. As Middle East Eye reported, ‘This support is closely linked to Abu Dhabi’s interest in the African country’s vast agricultural and mineral resources.’

In early 2025, Sudan brought a case against the UAE at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), accusing it of complicity in the conflict. The UAE dismissed the accusations as a ‘cynical publicity stunt’. On 5 May 2025, the ICJ dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction, citing the UAE’s reservation under the Genocide Convention. Serbia later filed a declaration of intervention in support of the UAE.

The influence runs both ways. For many developing nations, these investments represent major economic source of leverage. Countries that have secured their supplies may not only be more stable domestically – they may also be able to extract political concessions from others. The UAE’s ambition to become a global food-trading hub may prove central to this strategy.

But in the ruthless world of international politics, one country’s security can be another’s vulnerability. While securing food supplies might initially have been driven by a desire for domestic stability, it could in future be weaponised against others.

China’s dominance over rare-earth metals offers a cautionary tale. These materials are essential to modern electronics, and in recent years China has used access to them as a diplomatic tool – punishing rivals and rewarding allies. The fear among policymakers is that access to food could one day be wielded in the same way.