Victoria Heath speaks to five researchers on the fallout of political and financial upheaval following Trump 2.0

From climate science to maternal healthcare, research labs to ocean innovation, people across the world have felt the shockwaves of political and financial upheaval in the wake of Trump’s return as US president. Victoria Heath talked to five researchers whose work – and lives – have been reshaped in 2025.

Last in, first out

When Zack Labe lost his job as a climate scientist at NOAA, he was devastated yet, in part, relieved. After weeks of receiving harassing messages threatening layoffs, he and his colleagues would show up to work every day not knowing if it would be their last.

TURBULENT TIMES… click below to read all the stories

• Trump 2.0

• USAID Cuts

• Courtroom Drama

• Scientists Reeling

Read our full coverage of The Year That Changed The World

‘It just seemed like it was inevitable,’ says Labe. ‘We had this stress for weeks and weeks and weeks.’

Although now in his early thirties, Labe has been a self-professed ‘weather geek’ for as long as he can remember, keeping diaries of hourly weather conditions as a child with a homemade weather station. After studying meteorology at university, he was then motivated to continue a career exploring how climate change shapes extreme weather, especially in areas like the Arctic, where the environment is changing with particular speed.

But Labe, along with other probationary employees – those working in the US Civil Service with less than two years’ experience – were targeted in recent cuts, primarily because they have fewer job protections than other civil servants in the government. ‘We were kind of an easy target,’ says Labe.

At NOAA, Labe worked at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. His work focused on future climate projections and predicting climate extremes, using tools such as machine learning and artificial intelligence. In doing so, Labe’s research could help understand the impacts of extreme weather and its effects on communities.

In particular, one project Labe was working on before he was fired used AI to prepare for deadly heatwaves. Once completed, the research was set to identify areas across the US that would be more susceptible to extreme heat next summer, helping communities to prepare in advance. Yet such research never came to completion. Once Labe and his colleagues were let go, they lost access to their emails and the vast swathes of data they had collected for the project in a matter of hours.

‘It would have had very tangible impacts on improving societies and economies, as well as infrastructure,’ says Labe.

Labe, from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, has been fortunate enough to find another job – working as a climate scientist at Climate Central. There, his work focuses on improving predictions and understandings of future weather and climate extremes, as well as communicating this science to support decision-making.

For Labe, though, his concerns for the future lie with the next generation of scientists.

‘To me, it’s so important to continue to have the scientific pipeline for new ideas. These often come from students and early-career scientists, who are experimenting with new methods to try and improve our understanding of weather and climate.’

Time to leave the US

When Valerio Francioni left Great Britain in 2020, he was full of optimism. Having completed his PhD in neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh, he was heading to the US to begin a postdoctoral position at MIT.

His field, brain–computer interface research, is a niche area popularised by figures such as Elon Musk and his company Neuralink. Francioni’s work trains rodents to control a cursor on a screen using brain activity alone.

Such technology has enormous clinical implications, and could eventually help people who have suffered strokes or faced complete limb paralysis following spinal cord injuries, as well as treating epilepsy and certain forms of blindness. Unfortunately, Francioni’s optimism has wavered in the face of funding cuts under the Trump administration. Laboratories nationwide have needed to make more sacrifices as they grapple with limited cash.

‘If you cannot buy the best equipment, then you’re forced to do subpar experiments, which means the results you get are sub-optimal, and so are the conclusions you can draw from them,’ Francioni explains.

As well as strains on lab work, PhD programmes have also been cut at both MIT and Harvard, with rescinded offers an increasingly common occurrence. Hiring freezes are also happening more regularly in the sector, Francioni explains, making it difficult for people to navigate to new roles. Elsewhere, grants have been halted and then reinstated, causing major disruption to lab work.

Such seismic changes to the operations of the research sector are not without personal impact for Francioni.

‘On one hand, I’m in an incredibly privileged position,’ he says. ‘If it doesn’t work out in the US, I will have opportunities. I’m in a good spot – I’m qualified and have good training experience.’

‘On the other hand, I’ve invested in my career for so long. My original plan would have been to stay in the US for at least a couple of years and then apply for jobs elsewhere. That’s been my plan for the past ten years. I worked really hard for it, and then suddenly you have to change your plans.’

Because of the turbulence in the US, Francioni is now moving back to the UK to work as a biomedical engineer. ‘The US used to be the undisputed player in the research game,’ he explains, ‘because of its resources, salaries and the benefits associated with living here. But now, people are waking up to the reality that this might not be the case in the future.’

Global impacts

As the head of the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) – the world’s largest alliance working on women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health – Rajat Khosla has a unique vantage point on the state of global health. Having worked at PMNCH since May 2024, and with a career in human rights spanning years, Khosla explains he was drawn to his field of work after noticing the deep-seated patterns of inequality and discrimination that result in women being denied rights over their own lives.

Working with more than 1,500 partners across 130 countries, he has seen first-hand the impacts of financial cuts by organisations and donors, including the Trump administration.

In the last year, partner organisations in more than 20 countries across Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia have experienced a cascading impact of global disruptions, from reduced donor support to geopolitical instability, due to a range of financial cuts that include those enacted by the US government earlier in 2025.

According to a snap survey conducted by PMNCH, 89 per cent of partners faced reduced or uncertain funding in the last year. Sixty-two per cent had to downsize their programmes; 37 per cent temporarily suspended activities and 19 per cent were forced to permanently close initiatives.

As one partner explains, mobile health clinics were cut from operating across three days to just one, meaning vaccinations were interrupted and fewer pregnant women were reached. Others describe the sudden halting of programmes. One partner received notification to stop implementing their health programme with effect from 1 February, on 31 January. ‘This abrupt decision had a devastating impact,’ they say. ‘The sudden halt not only affected direct service delivery but also undermined the trust built with communities and government counterparts.’

For Khosla, statistics tell only part of the story. Each number represents a woman, child or adolescent impacted by a lack of healthcare.

‘More than 260,000 women die every year from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth,’ he says. ‘We still have more than 160 million people with an unmet need for contraception, and a high number of women who continue to experience unsafe abortions. The need hasn’t disappeared – but the support has.’

Khosla explains that a ‘cascading effect’ is occurring now, where several donors are either reducing funding dramatically or indicating that funding will cease, with money to be reprioritised elsewhere.

Amid such uncertainty, PMNCH is calling upon donors, policymakers and global leaders to protect and expand financing for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. Khosla believes that strengthening grassroots organisations and building coalitions and partnerships is a key way to safeguard the future.

‘One does worry what the next six to twelve months will look like,’ Khosla says. ‘Every delay, every funding cut, risks reversing years of progress. We need sustained investment and coordinated action to ensure that no woman, child or adolescent is left behind.’

Fears for the future

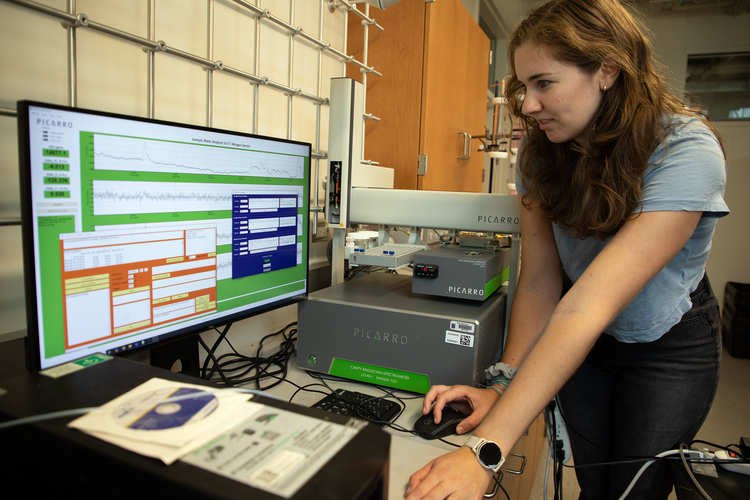

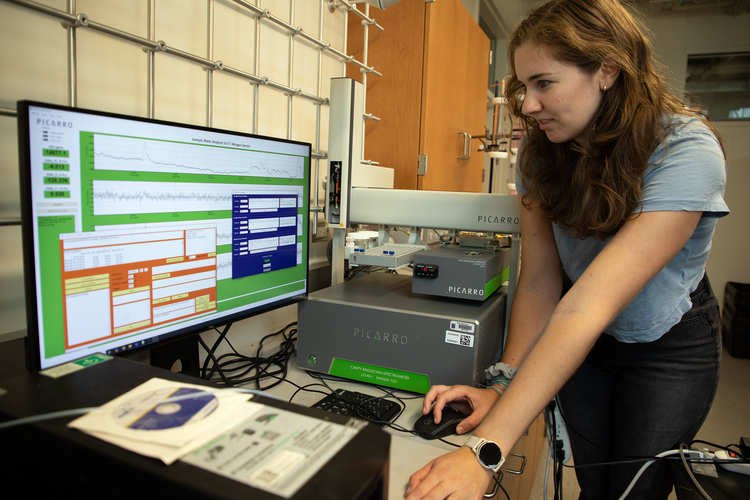

A PhD candidate at Duke University in North Carolina, Katryna Niva’s research is poised to help protect the planet. She is studying ocean alkalinity enhancement, a new climate-change remediation strategy where alkaline materials are added to the ocean. In turn, this helps to combat ocean acidification – a process that, if left untreated, can lead to weakened reefs, disrupted food webs and threats to food security for humans.

‘It’s a really cool and new topic, and a growing industry,’ says Niva. ‘It’s in its early stages, but it’s being upscaled very quickly.’

As part of her research into the effects of ocean alkalinity enhancement, Niva secured funding for a five- month internship in Newport, Oregon. There, she would be able to utilise a facility to advance her studies.

‘They have these huge, 3,200-litre tanks where you can bring seawater into them from the coast and change them in different ways, for example altering light levels or nutrients,’ says Niva.

Niva’s research would have been invaluable in understanding ocean alkalinity enhancement. ‘You’d have been able to see what safe levels of alkaline substances were, or at which point organisms would begin to be affected.’

However, after cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency, the facility in Oregon has been left on the brink of closure, leaving Niva to look for other opportunities to fill the research gap in her PhD.

‘It’s heartbreaking,’ says Niva. ‘It would have been an invaluable part of my dissertation, and it would have added a lot to the field. I was also really looking forward to working with some of the scientists. They were so passionate about what they did.’

‘It’s becoming more difficult to have a career in the US where you actually can have a positive impact on society. It seems crazy, but it’s the state we’re in, at least with the current administration.’

While Niva will still complete her PhD, she expresses concerns for those only just starting out.

‘I really feel for students trying to enter grad school right now. It’s a really tough landscape, and there’s just much less leeway for professors to have the capacity to take another student on.’

A loss of trust

It was 6pm on a Friday when Noor Johnson, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, received an email informing her one of her grants had been cut. She was not the first to receive such a notification; the Trump administration had already started terminating federal support for projects it deemed too DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) focused.

‘I think they enjoyed sending these emails out and ruining everyone’s weekend,’ says Johnson, who has been active in Arctic research for the last 18 years, working on collaborative research with communities about environmental change.

While Johnson’s research has taken her to the Canadian Arctic and Nunavut territories, as well as the vast plains of Alaska and northern Russia, her latest project would have involved heading to the Indigenous Ainu communities of northern Japan.

The project was set to work with the Ainu, using a collection of historic photographs in a workshop to look at how the environment and landscape have changed in the region across the last century.

When the grant for the project was terminated, the team were already midway through the planning stage. ‘We had already purchased half of the things we needed, so it was a big mess. It was difficult for us to have something we’d worked hard on suddenly cut.’

One PhD student involved had just been hired, having given up another opportunity to pursue the project that never came to fruition. ‘That was extremely impactful to her as an early-career researcher,’ Johnson says.

But despite the disappointment caused to herself and her colleagues, Johnson underscores how damaging such impacts can be to the communities they work with.

‘The biggest impact is on the trust of the community partners we’ve worked with.’