Stairwells and elevator banks have become the front line of immigration enforcement, where compliance offers no guarantee of protection

Photographs by Nicolò Fillippo Rosso

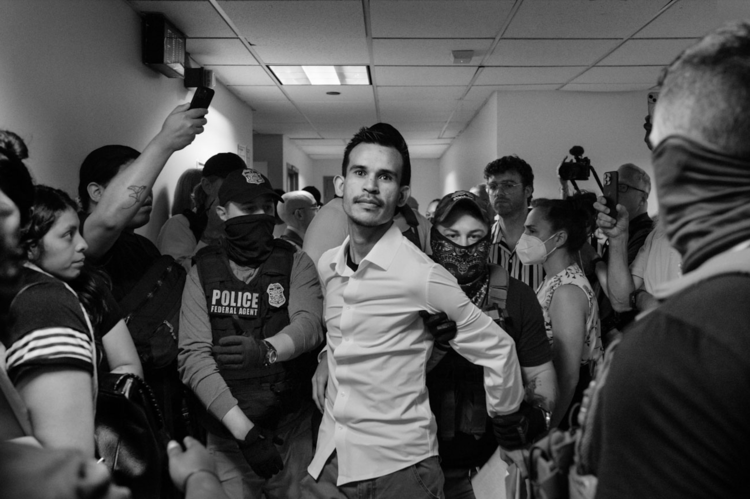

At an immigration court in central Manhattan, armed and masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents wait in the corridors and near the elevator banks, detaining people immediately after their hearings, regardless of whether a judge has granted them leave to stay while their cases are being heard.

Many of those taken into custody had complied fully with the legal process, attending hearings and filing paperwork, and have no criminal record.

The scenes inside 26 Federal Plaza court reveal the strain on families navigating the system. Parents stand in long queues with young children, clutching documents as they wait to learn whether they will be allowed to remain in the country. Clergy and community advocates accompany migrants through the process, often staying with families who fear leaving the courtroom after their hearings.

TURBULENT TIMES…click below to read all the stories

• Trump 2.0

• USAID Cuts

• Courtroom Drama

• Scientists Reeling

Read our full coverage of The Year That Changed The World here

In August 2025, the immigration-court backlog stood at around 3.4 million cases, nearly 2.3 million of them asylum applications. As of 21 September 2025, ICE was holing 59,762 people, with more than 70 per cent having no criminal records. Many detainees are transferred within hours to remote facilities in Louisiana, Texas or the Midwest.

The events around the courthouse also show the wider consequences of such enforcement. In one incident, a journalist was injured after being pushed from an escalator by federal officers while documenting an arrest, prompting concern from press-freedom groups.

Families from Venezuela, Ecuador, El Salvador and other countries describe the uncertainty of daily life: partners detained without explanation, children left without carers, and legal cases that can stretch for years. Attending court offers no guarantee of safety. Judges’ rulings are ignored. Asylum seekers are detained in an arbitrary manner and sent to far-off camps with no legal representation, often without their families knowing their whereabouts.

At 26 Federal Plaza, federal agents wait by the elevator bank – the only exit asylum seekers are allowed to use after a hearing. Compliance with the legal process doesn’t prevent arrest at the courthouse doors.

Respondents wait in line outside a Manhattan courtroom. Entire families queue for hours, often unsure how long the process will take. As of August 2025, the national immigration- court backlog stood at about 3.4 million cases, with more than 260,000 pending in New York.

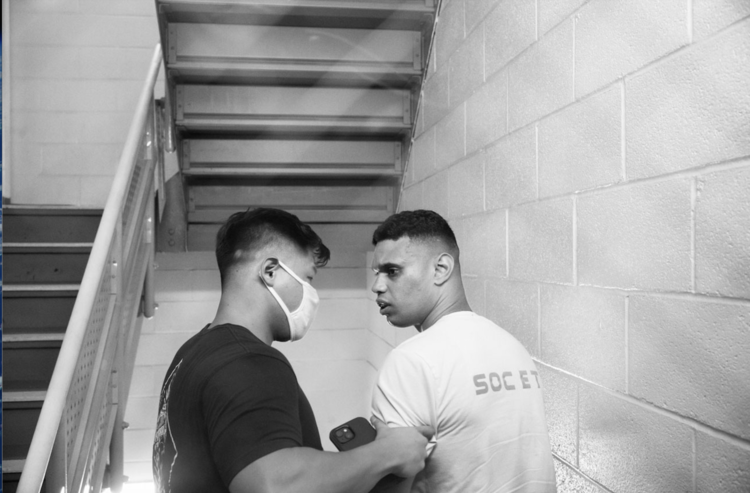

Father Fabian Arias accompanies migrants to their hearings each week. On 22 July 2025, Johnny P, an Ecuadorian migrant, was detained after a hearing but released minutes later.

A man is detained by ICE officers after leaving a courtroom hearing at 26 Federal Plaza. Detainees are frequently transferred to facilities in New Jersey, upstate New York or hundreds of miles away in the South and Midwest.

A transgender woman is detained outside a courtroom. In February 2025, ICE stopped publishing data on transgender detainees, despite a reporting requirement. Advocates warn that this increases vulnerability to abuse inside detention.

A doctor treats a journalist injured while documenting an arrest inside 26 Federal Plaza. Officers had pushed reporters over an escalator.

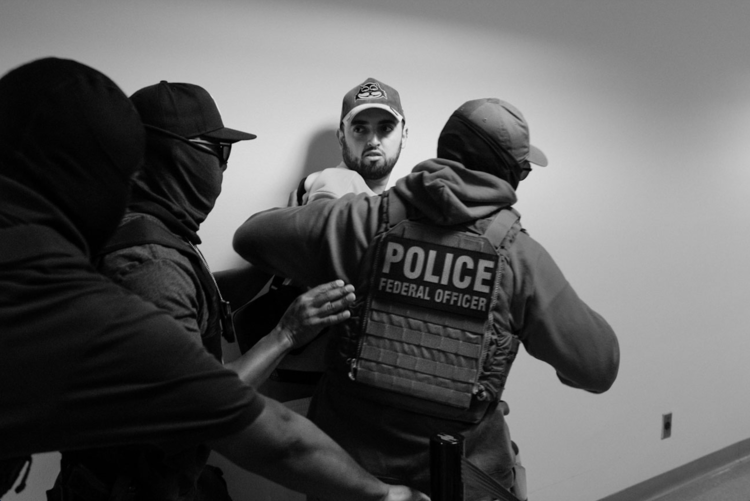

After his hearing, a man is escorted through a stairwell inside 26 Federal Plaza. Leaked footage from mid-2025 showed detainees held on the building’s 10th floor in a makeshift centre, sleeping beside unscreened toilets. A federal judge ordered conditions to be improved following public outcry.

A young man is detained after his hearing. In 2025, fewer than 40 per cent of immigrants in removal proceedings had legal representation; this fell below 20 per cent once detainees were transferred to remote facilities.

John, a cello player and music teacher, sings We Shall Overcome as he is arrested during a protest in Manhattan. Artists and citizens have held weekly actions in response to courthouse arrests.

Children from a Salvadoran family look at photos of their mother, who has been detained for more than four months. Their grandfather tells them she is ‘in jail because we are migrants’. By request of their lawyer, no identifying details are published.

Indira pauses during a meeting with her lawyer at St Peter’s Church. While her husband’s asylum case progressed, she and their daughters received deportation orders.

Franyelis Milagro Parra Olivares speaks on the phone outside 26 Federal Plaza after her husband was detained at his hearing. More than 400,000 Venezuelan asylum cases were pending nationwide in 2025.

Scarleth, 10, practices the butterfly technique during a remote therapy session, while her mother, Ana Lucía Guaman Buri, listens beside her in their Brooklyn apartment. The method, widely used in trauma therapy, asks the child to cross her arms over her chest and gently tap her shoulders in alternating rhythm, like the wings of a butterfly. Each tap helps ground her body, ease anxiety and create distance from overwhelming memories.

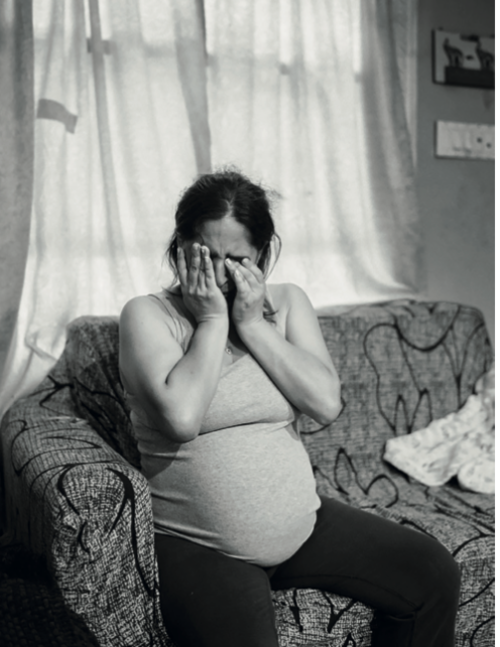

Jessica Maribel Supliguicha Espinoza attends a prenatal check-up in Queens. Weeks before her due date, her husband Jorge was detained after his hearing and deported to Ecuador.

In Queens, Jessica awaits the birth of her child after her husband’s deportation. Dylan, her autistic nine-year-old son, receives support in New York that would be difficult to access in Ecuador. Families in similar situations face the choice between safety and separation. For many respondents, information about why they are taken into custody is withheld from their families and even their lawyers until they are moved into the detention system.