What appears on the Ordnance Survey as a blank square kilometre of land is in fact a landscape rich with life, memory and meaning, Doug Specht reveals

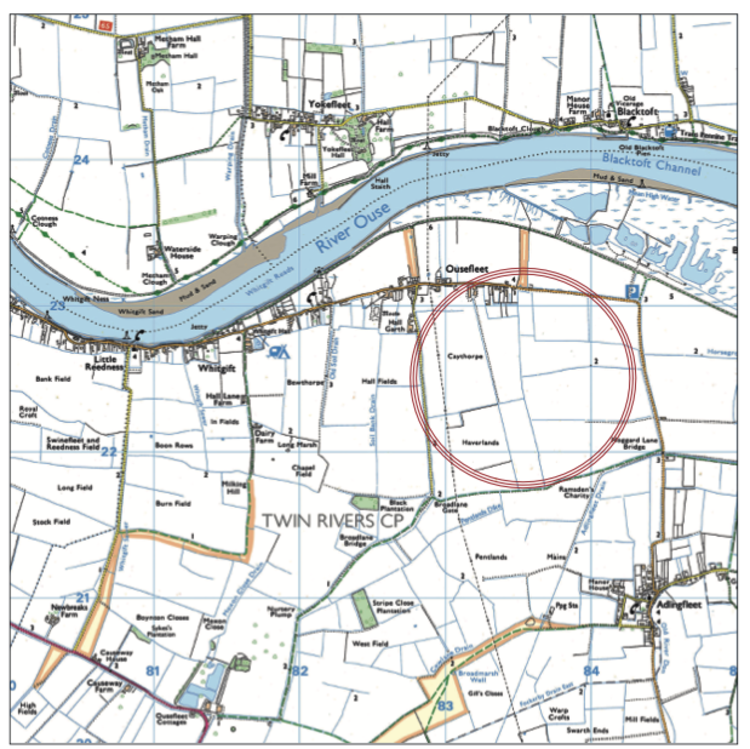

Look closely at an Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale map of the East Riding of Yorkshire and you’ll find something unusual east of Goole in grid square SE 8430 220 – almost nothing. No church symbols, no marked footpaths, no named buildings or prominent landmarks.

A handful of minor roads skirt past the square and the River Ouse threads along its northern edge, but otherwise the cartographers have left it nearly blank.

This is reportedly the least-detailed grid square in Great Britain, a one-kilometre-square expanse of flat, low-lying farmland where, according to the map, very little exists at all. In reality, the ground tells a different story.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

The village of Ousefleet sits just outside the northwest boundary of this grid. Its handful of houses, a church and the Millennium Green bench lie beyond the square’s edge, marked, albeit modestly, on adjacent sections of the map.

But the fields within SE 8430 220, which stretch from the river towards the settlements of Garthorpe and Luddington, are ones left blank. No footpaths are marked across these fields. Farm tracks exist, but they’re unmarked. Even the scatter of isolated farm buildings that dot the landscape nearby fail to appear on the map in detail.

The dykes critical to managing the landscape are only visible at larger scale. The OS map acknowledges land’s existence, but offers almost no guidance to what lies within. So what does exist in this ‘featureless’ square?

Open arable fields, primarily growing barley, wheat and sugar beet. Drainage channels maintained for centuries to keep the land workable. Hedgerows and field margins rich with wildflowers and insects. A surprising abundance of birdlife. And, crucially, the accumulated memory and labour of generations who have worked, walked and lived at the edges of this so-called emptiness.

RSPB Blacktoft Sands, one of England’s premier birdwatching sites, sits to the northeast of the grid square’s boundary, bounded by the confluence of the Ouse and Trent. It isn’t within SE 830 220, but its ecological influence radiates across the river and into the fields that are. The reedbeds, wetlands and marshes

of Blacktoft form part of the same hydrological and ecological system that makes SE 830 220 what it is: flat, fertile and deceptively full of life.

The blankness of the map belies the richness underfoot. Stand in the middle of SE 830 220 on a March morning and the supposed void hums with presence. Lapwings tumble and cry above ploughed fields.

Skylarks rise, invisible against the pale sky, their song stitching earth to air. In the ditches, those unmarked drainage channels, kingcups bloom yellow and dragonflies patrol in summer. Hares, which the map can’t record, lope across the stubble at dusk. Much of this abundance spills over from Blacktoft Sands and the wider fenland ecology.

Marsh harriers, which breed in the reed beds south of the Ouse, regularly hunt across the fields of SE 830 220, their low, leisurely flight a common sight for anyone working the land. Bitterns, rare elsewhere, can occasionally be heard booming from the wetland edges. In winter, flocks of golden plovers and lapwings descend onto the fields, joined by whooper swans and pink-footed geese that use the area as a staging post on their long migrations.

Barn owls and kestrels work the field margins, relying on the very hedgerows and dyke banks that go unrecorded on the OS sheet.

Tree sparrows, once ubiquitous, now in sharp decline across Britain, thrive here in the scrubby edges. The ‘featureless’ square is, in fact, a critical node in a landscape-scale web of life, supporting species that depend on the mosaic of open field, water and marginal habitat.

None of this appears on the map. The bitterns are absent. The harriers are absent. The thousand lapwings, the barn owl ghosting along a ditch at twilight; none of it makes the cut. Cartography records infrastructure and toponymy, but it struggles with life itself.

For the people who farm SE 830 220, the grid square is anything but blank. Every field has a name, known locally if not recorded nationally. Labels, passed down and adapted across generations, never standardised, never mapped.

The dykes and ditches that structure the entire landscape are the result of centuries of labour. Drainage here is not a convenience but a necessity. The land, once marshland prone to flooding, has been won from water through slow, patient engineering. Every channel represents a collective act of survival and ambition, a negotiation between human need and the Ouse’s tidal moods.

The 1947 floods, still remembered locally, swept field gates off their hinges and turned pasture into temporary lakes. ‘The gates floated off toward Reedness,’ one resident recalls, ‘and cattle huddled by the road.’ That memory shapes how the land is managed today: cautiously, pragmatically, with respect for what water can do.

Yet none of this history appears on the OS map. The ditches, the memory of flood, the careful maintenance of sluices and pumps – all are invisible. The map suggests a static, empty geometry; the reality is a dynamic, lived relationship between people, water and soil.

History, too, is layered into this landscape, though the map offers few clues. The family names that echo through local memory – Usflete, Thompson, Wall – are not marked in SE 830 220. These are the surnames of those who held land, worked it, or left their trace in the stories passed down in pubs and parish records.

The Usflete family, medieval lords whose manor once stood near the village, have long since vanished, but their name persists in local knowledge. Their moated manor site is near the village proper, and while it appears in historical records, the OS map offers no acknowledgement.

What does it mean for a place to be ‘featureless’? The OS map makes choices about what counts as significant: roads, buildings, named topography. But a map is not a landscape. It’s a tool, optimised for navigation and legibility, not for understanding. The blankness of SE 830 220 isn’t a failure of the land, but a reminder of the limits of representation.

John Muir, the great champion of wild places, once wrote: ‘When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.’ SE 830 220 is hitched to the Ouse, to Blacktoft Sands, to the centuries of drainage and cultivation, to the migratory routes of birds, to the stories of families and floods. The map can’t capture that web of connection; it can only hint at geometry.

To stand in the middle of SE 830 220, unmarked, unacknowledged, nearly invisible to the passing cartographer, is to experience a kind of radical openness. The absence of labels invites attention. The lack of marked paths requires you to find your own way. The blankness becomes, paradoxically, an invitation to see more clearly.

On a late autumn evening, with the light slanting low across the ploughed fields and the first frosts silvering the stubble, SE 830 220 transforms. The sky, unobstructed and vast, fills with the slow, ragged skeins of geese heading south.

The air carries the distant call of curlew and the soft rustle of reeds bending in the wind. You can stand here and see for miles, not because the land is empty, but because it is open.

This is abundance of a kind the map cannot plot: the abundance of space, of quiet, of possibility. The fields lie fallow, or they are sown, or they are harvested, but they are always, in some sense, waiting – waiting for the next season, the next generation, the next witness.

The least-detailed square in Britain is, for those who pay attention, full. It is full of memories, full of dykes and ditches, full of labour and loss, full of stories layered like sediment. It is full of what cannot easily be named or fixed or reduced to a symbol on a map. And perhaps that is its greatest gift: it is a reminder that not everything worth knowing can be recorded. Some things must simply be walked, witnessed and remembered.

Its essence, it turns out, cannot be marked on any map. It is a field, a sky and the quiet abundance of a place left, by the cartographers at least, blank.