A journey through crushing sea ice, polar research stations and wildlife encounters reveals the Arctic in all its stark wonder

By

The first undisputed trip to the North Pole, by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, Italian airship engineer Umberto Nobile, and American Lincoln Ellsworth took place in 1926. On Norge, a semi-rigid airship, the trio flew from Spitsbergen in Norway across the North Pole and into Alaska.

Almost 100 years on from Amundsen’s expedition, I’m standing on the North Pole, more than 1,100 kilometres from the nearest land. Fewer than 1,000 people make it here each year. It’s an adventure made possible by Le Commandant Charcot – a polar icebreaker vessel making its 17th voyage to the pole since it first began carrying passengers here back in 2021.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

Dozens of us have disembarked the ship for this moment, all donning orange parkas to protect from the biting cold. With wind chill factored in, it’s –15°C outside. Other than these specks of orange flecking the horizon as people explore the pack ice, everything around us is pure white.

The horizon stretches infinitely – the same flat expanse and whiteness everywhere you look means there is little distinction between what is ice or sky. Turn left, and you’ll see white. Stare straight ahead, and it’ll be the same. If it weren’t for the ship’s presence orienting us back to where we’ve walked from, it would be all too easy to get lost. There are no rocks, no landmarks or distinctive patterns in the snow to discern where you’ve walked from or where you’re heading to. It’s disorientating, and a little unsettling – but it’s a sure-fire way to feel like an explorer.

Out on the pack ice, my snow boots and walking sticks crunch through the thick, untouched snow we’re permitted to explore – at times reaching halfway up my calves. Beneath this snow is an ice floe metres thick, composed of a mixture of multi-year ice and ice just a year old. This vast expanse of frozen water grows in the winter – by around 50 per cent – then shrinks in the summer. Beneath the thick ice we’re standing on lies water more than 3,900 metres deep. It’s a fact I try to forget about as we venture further and further into the snow, away from the gangway of the ship that we used to disembark onto the pack ice.

It’s a quiet, still day, with quite literally nothing around us. Except, of course, for the ship – whose navy-blue body juts out of the landscape as we look back at

it. In any other landscape, it would look formidable – here, it seems dwarfed by the sheer amount of whiteness all around. We continue onwards, my calves aching from the sheer force it takes to lift my feet up and out of the dense snow.

I quickly realise there’s another option: snowshoes. These distribute my weight onto a wider surface area, allowing me to ‘float’ on the surface rather than sink in – a handy addition that gives my calves a welcome break. Eventually, we reach a beautiful vantage point: the ship, in its entirety, framed in a sea of whiteness. It looks like a postcard, or one of those impossibly picturesque screensavers on a laptop.

To get here, Le Commandant Charcot – one of the most powerful icebreakers in the world – has churned through hundreds of kilometres of ice in the Arctic Ocean. It’s the only passenger ship able to sail through such remote regions. Using a strengthened hull and powerful propellers – weighing 300 tonnes each – it spins through thick ice like a blender, navigating through ice up to 2.5 metres in thickness. On board, the boat occasionally shakes and judders as this ice passes through its propellers, splintering off in huge chunks.

There are no physical attributes around to say we’ve made it to the North Pole – no ‘you are here’ post stuck into the ground (although the crew have placed a temporary sign outside to mark the occasion). Yet somehow, despite its yawning expanse of nothingness, this location has fascinated explorers for centuries; it has been the reason for countless expeditions and failed voyages by submarine, airship, aircraft and boat.

In fact, these waters have been the playground of inquisitive explorers for more than 500 years, hailing back to John Cabot’s first attempt to find the Northwest Passage in 1497. By the 19th century, the reasons to come so far north had become far more territorial, to achieve the act of being the ‘first’ to reach the pole. In 1845, these waters were the famed location of Sir John Franklin’s lost expedition, with two ships – HMS Erebus and HMS Terror – ending up trapped in the ice, leading to the deaths of all 129 crew members.

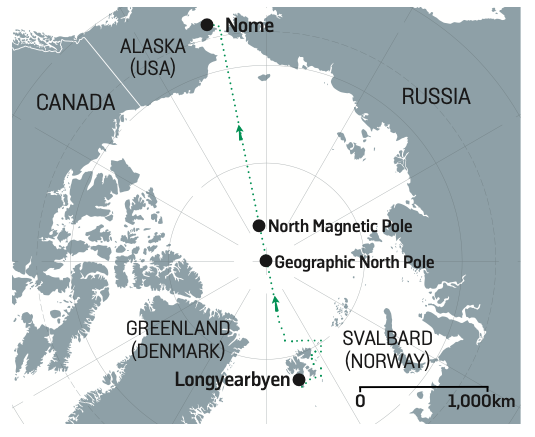

While reaching the North Pole has been the goal for many expeditions, our journey continues forward. I and 189 other passengers are undertaking a 20-day trip that has seen us set sail from Longyearbyen in Svalbard on our way to Nome, Alaska.

Because of climate change and the resultant melting ice, the once treacherous Northwest Passage and the regions around the North Pole are – as we’re experiencing first-hand – becoming more navigable journeys to make. This is a reality that invites major players on the global stage (think China, Russia, and the USA) to vie for geopolitical power in the Arctic. Access to such routes would enable shorter shipping journeys between the Atlantic and the Pacific, making it easier to avoid congested canals and potentially leading to huge reductions in cost. It’s a relatively new territory to explore, but one that many nations are eager to venture into.

Most modern-day expeditions to the North Pole are now driven more by the name of science than by any lingering sense of territorial ambition. It’s a collaborative endeavour, with dozens of research vessels making the journey each year to gather data and deepen our understanding of one of the most remote places on Earth.

Le Commandant Charcot adds another reason for journeying to these remote regions: tourism. Few ships make this journey, and fewer still offer the chance for paying passengers to stand at the top of the world. It’s an exclusive experience – expensive, yes, but also the trip of a lifetime. The ship straddles both worlds – being a research vessel with fully equipped laboratories below deck and a luxury passenger ship above. Onboard, polar researchers and experts travel alongside us passengers, leading lectures, workshops and field observations in the gaps between explorations on pack ice or heading out in Zodiac boats.

Throughout the lectures – whether they be on geoengineering, hunting in the Arctic or polar bears – one key point crops up time and time again: climate change is wreaking havoc upon the Arctic. Scientists on board are collecting data that, in various ways, will add to the body of research proving this. A team of researchers from Hamburg’s University of Technology drill deep into the ice throughout our trip, extracting a total of 40 ice cores across the three weeks. Together, these ice cores will help researchers investigate the strength of various types of sea ice and paint a clearer picture of sea ice drift.

Such research is vital, considering that Arctic sea ice is now shrinking at a rate of 12.2 per cent per decade. The region is warming four times faster than the global average, and as global warming intensifies, this trend is only expected to continue. Other scientists, such as Nicolas Cassar, are collecting water samples to aid understanding of the water cycle in polar regions. These findings will allow researchers back at his laboratory to glean new insights – into everything from moisture transport to the microphysics of clouds – helping to create more accurate climate models. On one bitingly cold morning, Cassar and I take samples of water that a piece of underwater equipment has collected from a depth of 1,000 metres.

As we funnel ice-cold water into bottles, Cassar tells me these samples will travel with him back to his laboratory at Duke University in North Carolina, around 6,000 kilometres away.

We also get up close and personal with research in Ny-Ålesund, the world’s most northerly permanent settlement and research base. Located on the island of Spitsbergen in the Svalbard archipelago, it hosts programmes from more than 12 countries for a variety of monitoring services, including those looking at Arctic foxes, polar bears and reindeer.

While we might be thousands of kilometres from the epicentres of greenhouse gas emissions – think major cities and conglomerate corporations – Ny-Ålesund has already begun to reel from the impacts of climate change. Back in February of this year, a team of scientists arrived at the typically snow-covered landscape to find melted ice and snow in its place. For half of February, Ny-Ålesund experienced air temperatures above freezing.

Vast, temporary lakes formed alongside large areas of snow-free tundra, and green plants were already beginning to grow. It’s a reminder of how far-reaching the impacts of climate change can be, a reality scientists have unfortunately become increasingly familiar with.

We further explore Ny-Ålesund with a guided walk outside the main village. At all times, the guide has a firm grip on their rifle – a precaution in case

of contact with a polar bear. Guides assured us that shooting a bear would be the last resort. Instead, they prefer to use flares that would scare off a polar bear without injuring it.

Encountering a polar bear in the wild seems like a far-flung dream. But, as I come to learn in the next few days, it’s not an impossibility. On several occasions, we spot polar bears from the ship as they slink around on the sea ice. There’s an encounter that requires me to use the high-zoom telescopes on the deck, and for a few seconds I glimpse a polar bear walking by on a rocky shore. In another instance, a polar bear comes so close to the ship we don’t need binoculars or a telescope. We watch for around ten minutes as it plods between floating pieces of sea ice, occasionally swimming between them.

It’s a sight, I come to learn, that is likely to become less and less common in the coming decades. In nearby Greenland, polar bears have already learned how to hunt without sea ice, instead relying upon glaciers and the resulting chunks of freshwater ice breaking off them. It may be a temporary solution; experts caution that glacial habitats are unlikely to be able to support huge numbers of polar bears. These marine mammals are expected to experience a marked decline across the Arctic under climate change.

Polar bears aren’t the only species we encounter, and are certainly not the last to be threatened by the impacts of a warming planet. At Torellneset, a sandy point on the northeastern coast of Svalbard, we spot a group of about 100 walruses lying around on a rocky outcrop. These large gatherings are known as ‘haulouts’, congregations often formed due to rising temperatures and a lack of sea ice to lie on. Such gatherings can lead to deadly stampedes in which young calves are trampled, and they also leave adults far from food sources.

Throughout our time at sea, we spot Arctic terns, the species that holds the title for the longest migrations. They travel between the Arctic and Antarctica in a 90,000-kilometre stint each year. This seabird is reeling from a warming climate – breeding numbers are decreasing at key sites as migration winds and habitats begin to alter.

Landscapes, too, are changing. In Monacobreen, we spend a morning near a towering turquoise glacier. Suddenly, there’s a boom, like a gunshot shattering the silence. A few seconds later, huge chunks of ice calve away from the glacier and fall into the water. A gaping hole is left in the glacier’s front. It’s not the first calving we witness: the guides tell us how unusually active the glacier is, as more ice continually breaks away, leaving lapping waves in the water as they fall down. While calving is a natural process, the rate and scale of it has increased at unprecedented levels thanks to climate change.

The Arctic may be one of the most remote regions on the planet, yet it remains one of the most intensely observed. It has captivated explorers hailing back more than 500 years to present-day researchers eager to extract scientific data from its landscapes. Tourism, as Le Commandant Charcot shows, is emerging as another reason to head to these regions.

From its glaciers to its flora and the plethora of wildlife that inhabits its barren landscapes, there is one resounding conclusion that such scientific research makes: the Arctic is changing faster than anywhere else on the planet. By the 2030s, this could translate to an ice-free Arctic Ocean in the summer; by 2100, temperatures in the Arctic could rise by up to 15°C if no measures are implemented to protect it.

Planet-polluting activities and industries continue to wreak havoc on a region thousands of kilometres away, a region whose future balances precariously on the climate actions – or inactions – of nations and corporations worldwide. Of course, there’s no debate – the Arctic is certain to look and behave differently from its present-day self. How quickly that happens, though, depends on how the rest of us respond to a region that is as unique as it is fragile.

Victoria travelled as a guest of Ponant on board their luxury icebreaker Le Commandant Charcot’s transarctic journey to the poles. Discover more about Ponant’s unique Arctic expeditions and other unforgettable voyages.