Despite some unusual data, a new study of the Earth’s magnetic field suggests that the poles are unlikely to flip for a long time

By

As satellites pass high over the South Atlantic Ocean, strange things start to happen. Instruments can malfunction, power boards can reset and detectors can record glitches in astronomical data. This all takes place in an area known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, an unusually weak point in the Earth’s magnetic field that’s rapidly growing, causing some scientists to speculate that we’re heading for a polar reversal.

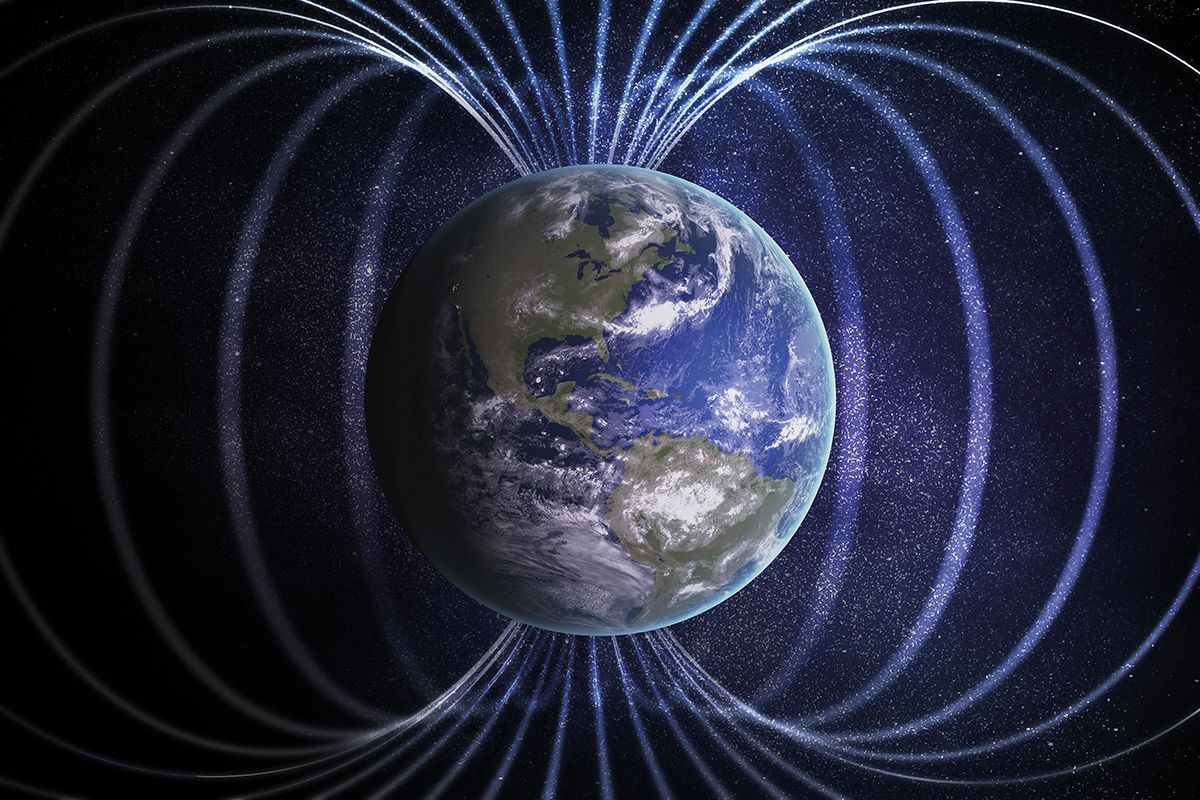

Like a bar magnet, the Earth has a dipole (two poles) magnetic field. But unlike a bar magnet, the Earth’s field is unstable. It’s generated by the movement of the flowing molten iron at our planet’s liquid outer core, changes to which cause the field to wax and wane in strength, shifting the position of the magnetic poles. From time to time – every 200,000–300,000 years or so – the poles switch places entirely.

Numerical simulations show that in the lead-up to previous polar flips, anomalies appeared in the magnetic field a bit like those being observed today, leading to speculation that we’re gearing up for another reversal. But Andreas Nilsson, a geologist at Lund University in Sweden, doesn’t think that we’re due one just yet. Nilsson’s research focuses on reconstructing the global variations of the magnetic field over the course of the past 9,000 years. Records of these variations can be found in volcanic rocks, neolithic pottery and sediment cores from lake and ocean floors. ‘The further you drill down, the further back in time you go,’ explains Nilsson. ‘As these layers of sediment are being deposited, you get magnetic grains, such as magnetite, that align themselves to the magnetic field,’ revealing the direction and strength of the field at different times and locations.

From these records, Nilsson and his colleagues at Lund University have found evidence for recurrent magnetic-field anomalies, similar to the one that exists today. ‘We can see a repeating pattern over the past 3,000 to 4,000 years,’ says Nilsson, adding that the Earth’s strongly asymmetric field around 600 BCE could be comparable to its current one. ‘If we look at that repeating pattern, it suggests that, over the next 300 years, the South Atlantic Anomaly will disappear and the dipole will stabilise again.’

At some point in the future, the poles will flip again, as they have hundreds of times before, but Nilsson estimates that it will take ‘roughly 1,000 years before we reach a reversal’. While the exact impact that this will have on life on Earth is unclear, some fear that the consequences could be devastating. Nilsson isn’t so sure. ‘There are no historical links between polar reversals and mass extinctions,’ he says. ‘Animals that use the magnetic field to navigate have survived previous reversals. It’s such a slow process that they have time to evolve and adapt.’

Often described as a flip, a polar reversal is more of a slow morph, taking anything from 3,000 to 10,000 years to complete. During this process, however, the protective shield of the magnetic field will weaken, exposing us to more solar storms and damaging electronic disruptions. Ultimately, it could be the technology we have come to depend on that could leave us most vulnerable in the future.