Marco Magrini warns that we shouldn’t assume that dramatic change can’t suddenly happen

Off the charts’ is the appropriate phrase. The scale of climate anomalies recorded during the first half of the Northern Hemisphere’s summer is staggering, to say the least. The ever-rising average air temperature, the intensity of the heat waves, the sea-surface temperatures and the narrowing extent of sea ice around Antarctica – where it’s now winter – are undoubtedly off the charts. July 2023 has already been billed as the hottest month in 120,000 years.

Climatologists and other professionals who track the planet’s energy imbalance confess they’re scared, as the current anomalies are too much and, well, too anomalous. The scientists’ concern is that the whole system – while heating at an unpredicted pace – may reach a tipping point sooner than predicted. Events such as an accelerated melting of Greenland’s ice cap or an abrupt thaw of methane-rich Arctic permafrost would be irreversible. A new study by the University of Copenhagen even warns that the Gulf Stream, the oceanic current that brings hot water and weather to northwestern Europe, may collapse sooner than once feared.

Even if those spooky climate charts aren’t displayed during daily newscasts, the general public may have had good reason for being equally frightened. Up to 1 August, 121,000 square kilometres of Canada’s boreal forests – an area bigger than half of Great Britain – went up in smoke. And the smoke headed southwards, choking New York, Chicago and Philadelphia for days. Meanwhile Phoenix, in Arizona, experienced 31 consecutive days without the temperature ever going below 32.2°C. In the Chilean Andes, again in wintertime, a temperature of 37°C was recorded.

Elsewhere, on every continent, a host of climate-supercharged local events have disrupted livelihoods with spectacular intensity. A list of every drought and flood, blizzard and wildfire, cyclone and hurricane that occurred during the first three-quarters of the year would require this entire page (Wikipedia is keeping an inventory under its ‘Weather of 2023’ entry). However, the general public still appears to be less worried than the climate cohort. Human beings tend to favour an observation of reality from their local standpoint. That’s why you may hear people say: ‘Weather extremes always happened.’ They did, but never at this scale.

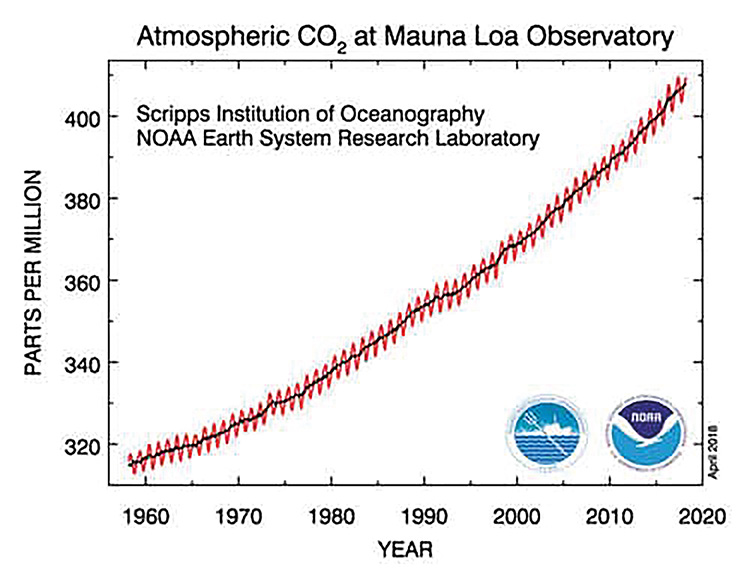

In 1958, climate scientist Charles Keeling started keeping track of atmospheric CO2 levels at the unpolluted Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. The first reading was 317 parts per million (ppm), or 317 CO2 molecules for every million molecules in the air. The Keeling Curve has been charting our common journey towards climatic uncertainty ever since, with its typical zigzagged course the result of the huge CO2 uptake by northern forests during spring and its natural release in autumn. The curve has kept on heading upwards, inexorably. Last month, on 3 August, carbon dioxide concentrations were at 422 ppm.

Even though CO2 isn’t the only greenhouse gas out there, the relationship between the Keeling Curve and the mean global temperature has been roughly proportional, with each ten ppm increase leading to a temperature increase of about 0.1°C. The course of the CO2 graph isn’t exactly linear – human-made emissions have been increasing – yet our long-term perception confirms that sense of linearity: extreme weather and heat have gone hand in hand with our growing addiction to fossil fuels.

However, in 1987 another foresighted scientist, the paleo-climatologist Wallace Smith Broecker, wrote a commentary in Nature professing a terrible doubt: that changes in the Earth’s climate may be sudden rather than gradual.

More Climatewatch columns from Marco Magrini…

‘We play Russian roulette with the climate, hoping that the future will hold no unpleasant surprises,’ he warned us 36 years ago.

The truth, as opposed to our deluded perception, is that the Earth’s climate is non-linear. Its dynamics are extremely complex and the relationships among its many factors are too intricate. The current off-the-charts data from the oceans and other equally scary climate anomalies tell us that something unsettling is going on. We shouldn’t take linearity – nor luck – for granted.