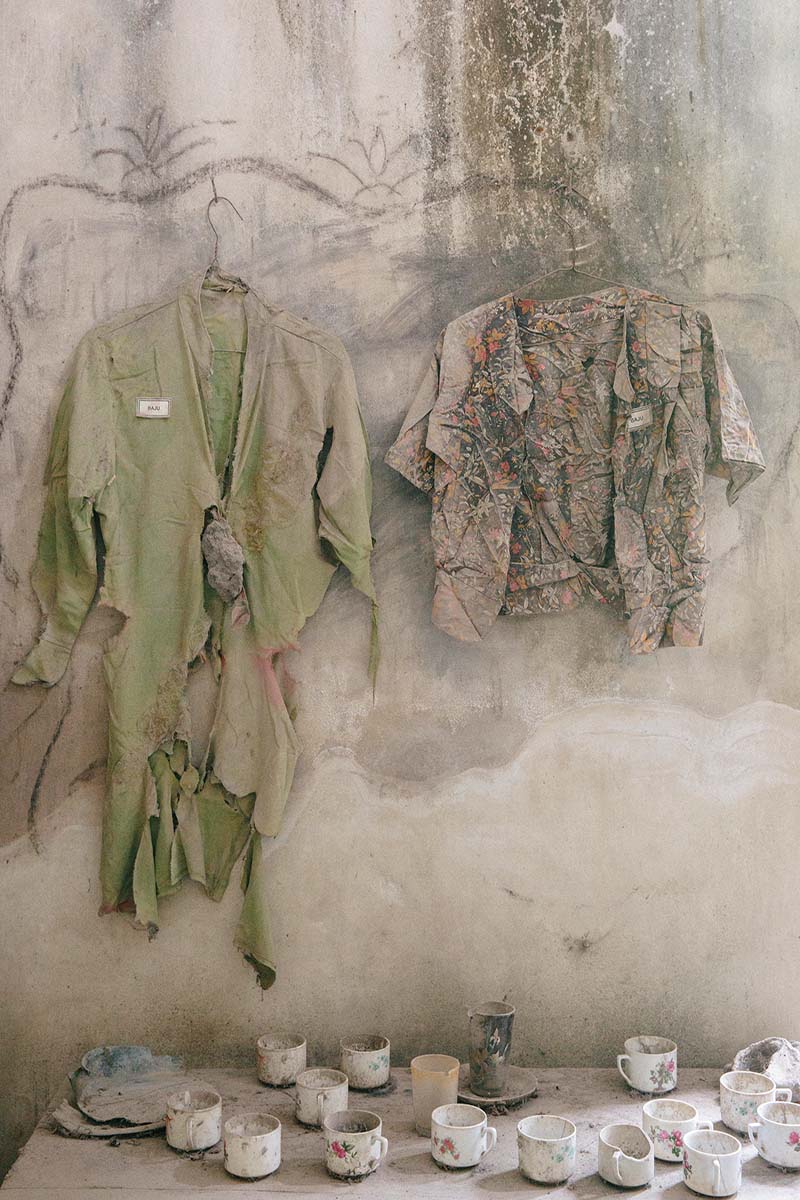

In Indonesia, more than five million people live close to active volcanos. Photographer Putu Sayoga set out to document the lives of those who live so near to potential danger

Words by Katie Burton, images by Putu Sayoga

All of a sudden, the day turned into night, chickens returned to their coops, and there was a thunderous sound coming from Mount Agung. From a distance, a continuous burst of fire appeared from the top of the mountain, followed by the falling ash rain.

‘That was what my grandfather told me about the Mount Agung eruption in 1963, which is still ringing in my mind,’ says photographer Putu Sayoga. He never forgot the story and never forgot the people who live so close to Indonesia’s ticking time bombs.

‘In 2017, the biggest volcano on my home island erupted again, so I went there to cover the story,’ he explains. ‘Gladly, the eruption was not that big, but I was curious about the people who live around it. They looked so calm and relaxed, even though black smoke spewed from the volcano. The relationship between the volcano and the people is what drove me to start this project.’

From Mount Agung in Bali, Sayoga began to expand his project to cover other volcanoes across the archipelago – on the islands of Bali, Java and Sumatra, and the North Moluccas – and to document the lives of the people who live so close to danger.

Just like the men and women near Mount Agung, who seemed so calm even as the volcano erupted, again and again Sayoga met people living in surprising peace with their sometimes violent neighbours. Acutely aware of the danger close by, many had developed rituals and practices to help them come to terms with it, and even to celebrate the volcanoes. They knew the risks but faced them calmly. It’s something that researchers in Indonesia have also documented and sought to understand.

The phenomenon may exist because, for many people in Indonesia, rumbling, lethal mountains are an unavoidable part of life. There are at least 130 active volcanoes in the country, with many located near densely populated areas. The country’s National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) recorded at least 156 volcanic eruptions across Indonesia during 2010–20 – an average of 15 eruptions a year.

Researchers use the Volcano Population Index (VPI) to measure how many people live within a certain distance of a volcano. The USA, with around 169 active volcanoes, has a VPI10 (the number of people living within ten kilometres of a volcano) of only a few thousand because most volcanoes are situated in isolated locations such as Alaska. But in Indonesia, the VPI10 is five to ten million people.

Visiting in 2016, shortly before Mount Sinabung in Sumatra erupted, an event that killed seven people, researchers Gavin Sullivan from the University of Coventry and Saut Sagala from the Institut Teknologi Bandung noted in an article that while their team was ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice in the face of pre-eruptions that ‘sent huge plumes of superheated gas into the sky as well as down the slopes of the mountain towards inhabited villages… this contrasted with the calm and – sometimes – complete indifference of locals.’

These were people living and working near or within the ‘red zone’ – the restricted area within three kilometres of the summit. Among them were many who would have seen the volcano erupt before. In 2010, after a 400-year hiatus, Sinabung roared into life and the volcano has been continuously active since September 2013.

For those of us who live far away from most natural disasters, moving away from an active volcano would certainly seem preferable. But in Indonesia, many people stay put. Often, this is because there’s little choice and, for agricultural communities in particular, volcanoes offer a valuable reward.

The World Disasters Report 2014, produced by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), sought to answer why so many people around the world live in dangerous locations. It found that: ‘Most people who live in places that are exposed to serious hazards are aware of the risks they face, including earthquakes, tropical cyclones, tsunami, volcanic eruptions, floods, landslides and droughts. Yet they still live there because, to earn their living, they need to, or have no alternative. Coasts and rivers are good for fishing and farming; valley and volcanic soils are very fertile; drought alternates with good farming or herding.’

In addition, research suggests that people’s sense of risk can be tempered by religious or cultural beliefs. The IFRC report noted that: ‘Culture and beliefs, for example, in spirits or gods, or simple fatalism, enable people to live with risks and make sense of their

lives in dangerous places. Sometimes, though, unequal power relations are also part of culture, and those who have little influence must inevitably cope with threatening environments.’

This rang true for Sayoga as he undertook his photography project. He found that ‘people living close to the volcanoes usually have rituals to worship the volcano gods.’ What particularly surprised him was that in some areas, people seemed openly willing to sacrifice their safety in return for the volcanoes’ reward of fertile land. ‘In some places there are still old beliefs – like the volcano already gives you everything, so it is okay if the volcano wants to take it back. I think that’s also why they don’t have any problem living close to the volcanoes.’

In fact, despite the enormous danger volcanoes can pose, they don’t appear to be a significant factor when it comes to encouraging migration. A 2014 study by social scientists from Princeton University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that looked at migration between provinces in Indonesia found that changes in the average temperature of a region and, to a lesser extent, changes in the annual rainfall were much more significant than natural disasters when it came to the reasons people move.

The study used data from the Indonesia Family Life Survey, which follows more than 7,000 families from 13 of the most populous of Indonesia’s provinces, contacting them every few years to see how their lives have changed. The researchers found that average temperature had by far the greatest impact on the number of people moving and staying in their new homes. In contrast, the effects of natural disasters such as earthquakes and volcanoes on permanent relocation were statistically insignificant, suggesting that people who left their home provinces after disasters tended to go back as soon as conditions returned to normal.

However, none of this means there aren’t serious risks to living near active volcanoes, or that millions of lives haven’t been affected in recent years. The eruption of Mount Merapi in central Java in 2010 killed more than 250 people and saw thousands flee their homes. The volcano is the most dangerous in the country but more than one million people live within a ten-kilometre radius of the summit, putting them at constant risk. Hundreds of lives have been lost due to its eruptions since the 1990s. When Mount Kelud, a volcano on the island of Java, erupted in February 2014, nearby villages were blanketed with ash and other debris. An estimated 100,000 people fled, becoming internally displaced, at least temporarily.

To help more people in the wake of such disasters, experts are now recognising the need to take into account local attitudes when planning disaster-risk management in Indonesia. Simply recognising that people don’t want to leave, often because their entire livelihoods are dependent on the land, is important. Speaking to the New Humanitarian, Ahmad Husein, a spokesperson for the IFRC in Indonesia, noted that: ‘People are worried about their cows – who is feeding [them]. They ask: “Will you take responsibility when our cow is dead because we are in the shelter and can’t feed it?”’ Husein noted that people often sneak back to their farms while an eruption is in progress in order to feed their cattle.

Their concerns are certainly valid. During the 2010 Mount Merapi eruption, the BNPB recorded 2,800 cattle deaths, while around 12.4 per cent of the total economic loss of 4.23 trillion rupiah was due to the loss of small- and medium-sized businesses, including in the agriculture and livestock sectors. Understandably, people will sometimes risk their lives in order to safeguard their livelihoods – particularly if they have a family.

To address this issue, the Indonesian government says that it has started to incorporate the evacuation of livestock into the contingency plans of several districts. In 2022, Lieutenant General TNI Suharyanto, the head of the BNPB, noted that the government has integrated livestock evacuation as a new and important element in disaster-mitigation efforts, especially in volcanically active areas. According to the Indonesian News Agency, the Ministry of Agriculture is now working with the BNPB and local governments to prepare guidelines for handling livestock during volcanic disasters, which include arrangements for livestock evacuation and contingency plans.

In Indonesia, it’s impossible to move everyone away from danger. Risk management, early-warning systems and solid evacuation plans are therefore essential. For all of these to work, the local reality has to be taken into account and the incredible resilience of the Indonesian people better understood.