Iceland is a sparsely populated country with one of the most geologically and volcanically active landscapes in the world, perfect for capturing some of the most striking landscape images on Earth

By Keith Wilson

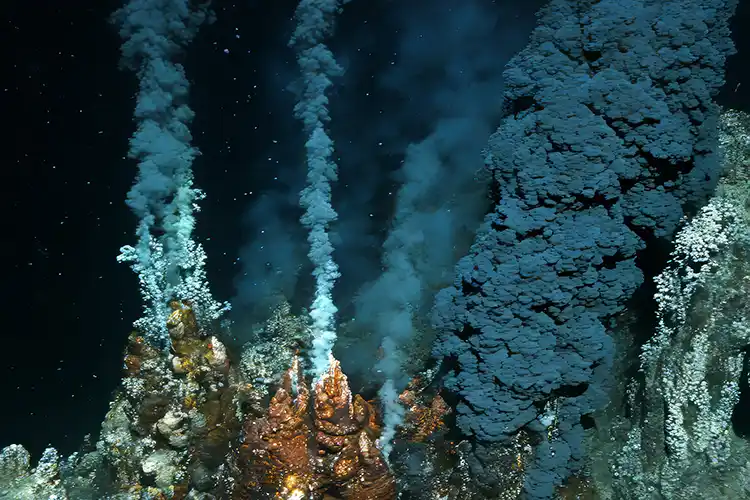

Sitting just below the Arctic Circle and above the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that marks the junction of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, Iceland is home to active volcanoes, spouting geysers, thermal springs and frequent earthquakes. Geologically speaking, this is a young land, undergoing constant reshaping by Earth’s subterranean forces. Above ground, the landscape is further altered by the shifting ice of Europe’s largest glaciers, torrential waterfalls and a climate that is almost impossible to forecast. It’s this turbulent, volcanic landscape that makes Iceland a such popular destination for photography.

Although it is a remote island with a small population and little impact on global politics and economics, Iceland nevertheless grabs the world’s attention whenever there is a major eruption from one of its 30 active volcanoes. This seismic landscape is a major draw for visitors from overseas, captivated by the thunderous waterfalls, vast inland glaciers, towering sea cliffs and iceberg-strewn beaches that feature prominently in any excursion from the modern comforts of affluent Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital city. Since 2000, tourist numbers have increased eight-fold to around two million every year. Many are keen landscape photographers, travelling together on specialist photo tours to focus their cameras on the country’s natural wonders.

You may also like

Nearly all such trips begin from Reykjavik, and most stick to the southwest corner of the island, before heading east along the south coast. Major viewpoints include the waterfalls of Skógafoss, Gullfoss and Seljalandsfoss, the black sand beach at Reynisfjara and the Jökulsárlón glacier lagoon. These landmarks are particularly popular between May and September when visitors take advantage of the long summer days and warmer average temperatures. Other southern Iceland photography highlights include Dyrhólaey, a coastal rock arch reminiscent of Dorset’s Durdle Door, and Geysir, the original spouting hot spring after which all the world’s geysers are named.

Steamy eruptions

Geysir’s known existence dates back to the late 13th century when it was first mentioned in Icelandic literature following a series of major earthquakes and the eruption of the nearby Mount Hekla. It may have the history, but it is the nearby Strokkur geyser that has the reliability. Situated just a hundred metres away, Strokkur may be smaller, but it is the preferred choice of many photographers as it erupts every ten minutes or so. Timing is important when photographing any geyser, and one that erupts as frequently as Strokkur makes planning and preparation a lot easier. For the first-time visitor, it makes sense to simply let the first eruption or two pass without taking a picture, and instead observe how long the eruption lasts and the height of the spout. Make note of the direction and strength of any wind as this will influence where you should stand. Geysers are scolding hot after all!

The height and general size of the geyser will also determine your choice of lens. Also note the sun’s position: is it behind you or to the side or even behind the geyser, backlighting the plume of steam and spray? The background sky also plays an important part in any composition – preferably a blue sky, even partially cloudy, is preferable to a grey overcast day as geysers aren’t naturally colourful. So, a blue sky background, clear sun adding highlights to the edge or behind the spouting spray, and a slight breeze are the ideal conditions for the photographer. A frequently erupting geyser like Strokkur also provides opportunities to experiment with shutter speeds to get a variety of effects, from the smooth cotton-like plume of a long exposure to the intricate detail of every airborne droplet, revealed by a high-speed shutter release.

Waterfall wonders

The hot water dramas of Iceland’s geysers are more than matched by the cold water wonders of its abundant waterfalls. As any visitor will tell you, Iceland’s waterfalls are spectacularly different. Gullfoss is probably Iceland’s most visited and is known as the ‘golden waterfall’. It has an unusual two-tiered, 32 metre drop that may be modest compared to others, but its setting within a narrow 70 metre deep, 2.5 kilometre long canyon is without compare.

Along the south coast Seljalandsfoss plummets 40 metres down a cliff face on the Seljalandsá River. As well as affording visitors a great view of a classically shaped waterfall, Seljalandsfoss is also popular for the unique curved shape of the cliff which allows people to walk behind the curtain of water at the foot of the falls. Care has to be taken walking along the path and despite the constant spray, it is impossible not to stop and take a picture from behind the fall. Further east along the coast road lies an even bigger waterfall, the mighty Skógafoss, with a 60 metre cascade of water finishing its descent from the Eyjafjöll mountain range, home to the notorious Eyjafjallajökull volcano. The huge amount of spray produced by this massive fall means rainbows from the falls are a common sight on sunny days.

Each of these waterfalls is impressive in scale and volume, but one of the most picturesque is Svartifoss, fed by the meltwater of the Svinafellsjökull glacier. Located within Skaftafell National Park, Svartifoss means ‘black falls’ in Icelandic and gets its name from the black basalt columns of the cliff face behind its 20 metre drop. These impressive hexagonal columns were formed inside a slow-cooling lava flow and similar formations can be found on the Hebridean island of Staffa and at the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

Water with ice

The basic photographic technique is the same for all waterfalls, with framing a vital consideration for conveying the height and scale of the fall in relation to the background and surroundings. A tripod is vital for this purpose, but even more so for making a variety of exposures that cannot be executed by handholding the camera alone. For instance, do you wish to depict the falling water as a soft blur or with high speed clarity, where individual water drops appear suspended in space?

Shutter speed selection is the key to achieving the desired effect and with your camera on a tripod it is possible to create remarkably different images from the exact same position, and without changing lens focal lengths. Basically, the longer the shutter is kept open the more the waterfall will blur. An exposure of around two seconds will capture the falls as a white rush of frothing water, while longer exposure times, as much as 30 seconds or longer, will render the waterfall as a soft, fine white smudge. By running through the full range of shutter speeds and studying the effects on the camera monitor, it becomes easy enough to find your preferred image and the shutter speed that realized the result. Simply, your preferred shutter speed will be down to personal taste, but it could vary from one waterfall to the next.

Glaciers and lagoons

Of course, this is a land that owes its name to the vast quantities of ice to be found here, most notably in the form of the 13 major glaciers that cover over 11 per cent of the country’s surface. The largest is Vatnajökull, found within the national park of the same name. This is Europe’s biggest glacier, covering an area of more than 8,000 square kilometres, including many active volcanoes. The glacier rises to more than 2,000 metres at its highest point and is the location of many eruptions, most notably Grimsvötn, Iceland’s most active volcano of recent years.

The Vatnajökull glacier has a powerful influence on much of Iceland’s landscape, shaping the course and force of many rivers due to the movement of glacial ice and frequent volcanic activity. For example, the famous Jökulsárlón glacier lagoon is renowned for the icebergs which dot the still blue waters. It is undergoing constant change due to the glacier’s rapid retreat from the ocean – glacial melt has resulted in the size of the lagoon increasing fourfold in the past 40 years. As the water reaches the sea, large chunks of old glacial ice are left stranded on the black sand beach, making it another popular subject with photographers. The one drawback to Iceland’s ever-increasing popularity is that many photographers take up position side by side, tripod next to tripod, and end up taking the same pictures as everyone else. By all means, gain inspiration from this amazing landscape, but stand apart from the crowd and try not to recreate the images of those who stood before you.

Iceland photography tips:

Do

- Use a tripod. When photographing Iceland’s erupting geysers or tumbling waterfalls, a tripod gives more exposure options, particularly at slower shutter speeds. It is also essential when making multiple exposures.

- Check the date, time and direction of the next full Moon. During the winter months, a full Moon rises soon after sunset and will have a higher trajectory across the night sky. With a clear, dry night you’ll have perfect conditions to photograph not only the Moon, but also other subjects in the landscape that are visible under moonlight.

- Wear waterproof clothing and boots. Iceland’s changeable weather is notorious and even when the sun is out, the air is damp with mist or spray, and the ground wet or icy underfoot.

Don’t

- Immediately take a picture the first time you see a geyser erupt. Note the time between eruptions, its height, the background and position of the sun, then decide where is the best place to take your picture.

- Stray off the path or across marked boundaries. Iceland is spectacular but this is a wild and volatile landscape of high cliffs, slippery ice and powerful waterfalls.

- Attempt to recreate images that you have already seen. Some locations in Iceland are among the most photographed places on Earth, so experiment and try to create a picture you haven’t already seen.

Equipment selections

ACCESSORY: Carbon fibre tripod

Tripods come in all weights and sizes, but it is important not to compromise on strength or stability. Carbon fibre is as light as aluminium, yet far stronger. The Manfrotto MT055CX PRO3 (£350) features four-section carbon fibre legs that use clip-locks for height adjustment. There is a 90° pivot system for the centre column that is ideal for use with wide-angle lenses. Fully extended shooting height is 1.83m and maximum load bearing weight for the head is 8kg – more than enough for most camera/lens combinations.

www.manfrotto.co.uk

OUTDOOR GEAR: Camera backpack

The unique and varied terrain of Iceland means your camera kit is best balanced and carried on your back. While many camera backpacks have side openings for better accessibility, the Paxis Mt Pickett 20 (£220) allows the separate bottom section of the pack to swing round on a hinged arm to face you for effortless access to your camera and lenses. This so-called ‘shuttle pod’ is compactly designed and the entire backpack weighs just 2.5kg.

www.paxispax.com

CAMERA: Weather-sealed DSLR

Airborne spray from the sea, waterfalls and geysers is commonplace in Iceland so you need to be confident in the build quality of your camera. The Nikon D500 (£1,700 body only) is a rugged, weather-sealed, crop-sensor DSLR, aimed at the semi-pro market with a build and specification to match the latest full frame cameras. It’s a cropped sensor version of Nikon’s new D5 flagship model, but a lot more affordable!

www.nikon.co.uk

Recommended reading

Iceland: Above and Below by Hans Strand; Triplekite; £36.99

Iceland: Nature of the North by Jurgen Wettke; teNeues publishing; £65

Iceland by Ulrike Crespo; Kehrer Verlag; £40