The remarkable story of Cairo’s Zabbaleen, who turn the city’s rubbish into valuable resources in a stunning example of sustainability

Words and photographs by Claire Thomas

In the shadow of Cairo’s bustling streets, where the noise of honking horns and the smell of street food fill the air, a different rhythm pulses in the city’s underbelly. It’s a rhythm powered by waste – the discarded remnants of a metropolis of more than 20 million people.

Here, in run-down settlements scattered across the city, a group of people known as the Zabbaleen, meaning ‘garbage collectors’ in Egyptian Arabic, have turned rubbish into treasure, recycling up to 80 per cent of Cairo’s waste – a staggering feat in a world where most Western cities recycle less than a quarter of their refuse.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

The Zabbaleen are a community of predominantly Coptic Christian Egyptians who, for decades, have made a living by collecting, sorting and recycling garbage. Their story is not just one of survival but of resilience and ingenuity.

Amid the mountains of refuse that pile up across Cairo, the Zabbaleen have developed an informal yet highly efficient waste management system. Where many see only decay, they see opportunity.

With a population of between 50,000 and 70,000, the seven settlements where the Zabbaleen live are a patchwork of overcrowded neighbourhoods scattered across the Greater Cairo Urban Region, each serving as a sorting and recycling hub. The largest is Mokattam Village, the heart of the Zabbaleen community, nestled at the base of the Mokattam Plateau in the suburb of Manshiyat Nasser.

Nicknamed Garbage City due to the massive volumes of trash that fill its narrow streets, Mokattam is not only a place where waste is sorted but also where nothing goes to waste.

The Zabbaleen’s waste management system is a finely tuned collaboration shaped by necessity and tradition. At dawn, the men set out into Cairo’s streets, navigating the sprawling city with an array of vehicles: large, modern garbage trucks in affluent neighbourhoods and simpler pickup trucks or donkey-pulled carts in less privileged areas.

Their task is to collect the city’s refuse – an essential first step in a process that sustains their community. Back in the labyrinthine alleys of the Zabbaleen’s settlements, the women and children take over. In small, dimly lit homes or outside in the street, they undertake the painstaking task of sorting the waste.

Paper, metal, glass and plastic are carefully separated, with every salvageable item earmarked for recycling. The work is relentless, conducted amid the pungent smell of rotting food and the ceaseless mechanical drone of grinding machines. These heavy- duty machines, tucked into cramped spaces, transform discarded plastic into raw materials, ready to be sold and reintroduced into the manufacturing cycle.

One of the most striking elements of the Zabbaleen’s waste management system is their reliance on an unlikely ally: pigs. As one of the few groups in Egypt permitted to raise pigs, the Zabbaleen’s predominantly Christian identity plays a crucial role in shaping their waste recycling methods. In a country where the majority-Muslim population forbids the keeping of pigs due to cultural and religious norms, these animals are both a symbol of ingenuity and a linchpin of efficiency.

Pigs perform a vital function in the Zabbaleen’s operations by consuming food scraps, transforming organic waste into a resource rather than a burden. Their manure is also used as fertiliser, creating a circular system that maximises resource utilisation while minimising landfill waste.

‘Life here is very difficult for us,’ says Hanaa, a mother of five who lives in one of the Zabbaleen’s settlements. Hanaa’s apartment is a microcosm of the Zabbaleen’s resourceful yet arduous lifestyle: one floor serves as her family’s living space, while others are dedicated to sorting and processing garbage. On the rooftop, pigs are housed in makeshift pens alongside goats, creating an ecosystem where every scrap finds a purpose.

‘The pigs help us live,’ Hanaa explains. ‘They provide food and an income when we sell them.’

However, the practice of raising pigs is not without its challenges. For many Egyptians, the proximity of pigs to human homes is a contentious issue. This tension reached boiling point during the 2009 swine flu outbreak, when the Egyptian government ordered the mass culling of pigs nationwide. While the measure was framed as a public health precaution, it disproportionately affected the Zabbaleen, stripping them of a cornerstone of their waste management system and livelihood. The policy was never fully implemented, and despite such setbacks, the community persevered, rebuilding its pig population to sustain its essential work.

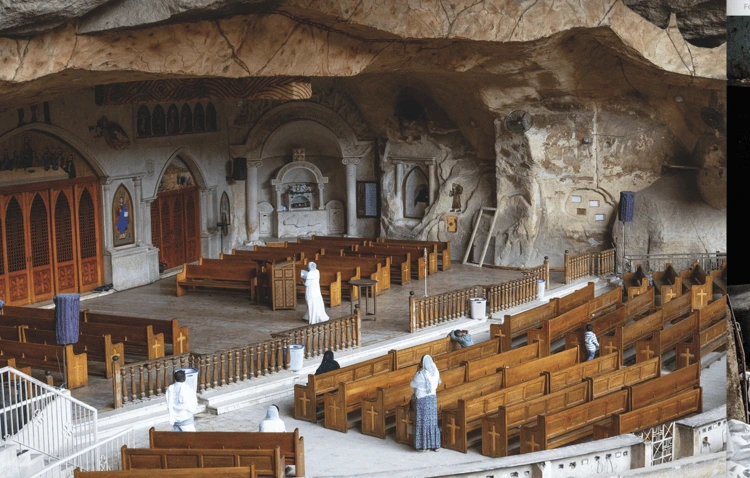

Mokattam Village is not only a hub for sorting garbage but a vibrant community. At the heart of the village lies the Monastery of St Simon the Tanner, an extraordinarily sanctuary carved into the rocky cliffs of Mokattam Mountain.

This awe-inspiring site is among the largest churches in the Middle East, capable of hosting thousands of worshippers in its vast, echoing interior. It’s immaculately clean and well maintained, in stark contrast to its nearby surroundings.

The caves of Mokattam are home to seven distinct cave churches, each intricately carved into the mountain and imbued with spiritual significance. These sacred spaces are adorned with detailed carvings, religious iconography and scripture, standing as a beacon of the Zabbaleen community’s deep Coptic identity. Here, amid the rugged surroundings, faith isn’t merely practised – it’s etched into the landscape, a source of solace and strength for the community.

Despite the success of their recycling efforts, the Zabbaleen aren’t without their challenges. They’ve faced repeated pressure from the Egyptian government, which has sought to formalise the waste management sector by introducing large corporate contractors and modern waste disposal methods. In 2003, for example, the government began working with private companies to take over waste collection from the Zabbaleen, pushing many out of the business.

However, the Zabbaleen’s established network, remarkably cost-effective methods and efficient operations proved too difficult for the corporations to compete with. The Zabbaleen prevailed and endured.

Their informal system – built on community and knowledge passed down through generations – remains unmatched in its ability to recycle so much waste with so little infrastructure. In a city where the garbage often overflows into the streets, their system offers a rare model of sustainability – one that’s rooted in the ingenuity of the people rather than in large-scale machinery.

The future of the Zabbaleen is uncertain. As Cairo expands and modernises, their once-reliable niche as the city’s primary waste collectors may erode. But in Mokattam and the surrounding settlements, their efforts continue to have a profound impact – not only on the city’s waste management practices but also on the larger conversation about sustainability and the environment.

While the world looks to global summits such as COP 29 for answers on climate change and waste reduction, the Zabbaleen’s approach offers a reminder that sustainability often starts at the grassroots level. These men, women and children may work in the shadows, but their efforts shine a light on what’s possible when a community takes ownership of its environment and when nothing – not even trash – is considered to be beyond redemption.

As the world continues to grapple with its growing waste crisis, the Zabbaleen remain a testament to the possibility of turning waste into a valuable resource. For the Zabbaleen, there’s no such thing as garbage – only raw material waiting to be re-purposed.