With more than 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic – and counting – The Great Pacific Garbage Patch has more plastic than living organisms

By

In the remote parts of the Pacific Ocean, you might expect to find waters untainted by pollution or human-related activities. But in these far-reaching corners of the planet lies concentrations of marine debris equivalent to approximately twice the size of Texas.

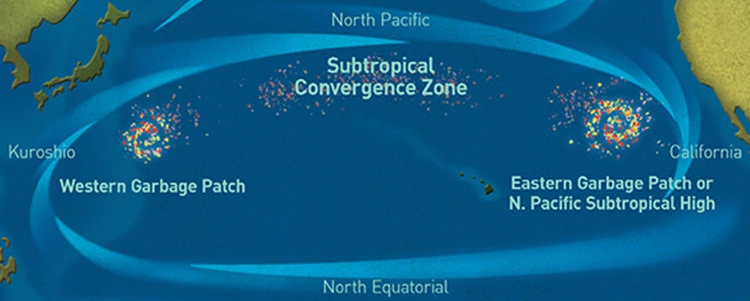

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, despite its name, is actually comprised of two areas of spinning debris, linked together by the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone and bounded by the swirling waters of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, whose circular motion draws debris into its centre to form the accumulation of debris.

New research – which examines a variety of samples from trawls, aerial surveys and cleanup extractions – has shown that the rate at which tiny plastic fragments are growing in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is much more rapid than scientists predicted.

In just seven years, plastic fragments in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch have risen from 2.9kg per sq km to 14.2kg per sq km. In addition, small debris hotspots increased in concentration from one million per sq km back in 2015 to more than ten million per sq km in 2022.

Enjoying this article? Check out our other marine reads…

So vast is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch that it is now home to a greater volume of plastic debris than living organisms – an imbalance which can have catastrophic impacts on our wildlife and planet.

What impact does the Great Pacific Garbage Patch have?

Each year, up to one million seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals are killed either via ingesting these tiny plastic fragments or becoming entangled in larger pieces.

The presence of microplastics could also impact our global carbon cycle. Zooplankton – vital for uptaking ocean carbon – can mistake very small plastic particles for food, reducing their ability to ingest carbon. Marine microplastics can also have toxic effects on these carbon storers, affecting their development and reproduction.

Another impact of the patch is what can attach itself to the floating pieces of debris – known as flotsam – that comprise it. While there has always been flotsam, like logs, lingering in ocean waters, the various qualities of plastic – high buoyancy, slow degradation – as well as its vast quantities, mean its debris can disperse further than traditional flotsam.

This allows ‘animal hitchhikers’ to inadvertently attach themselves to floating pieces of plastic and enter other fragile ecosystems, competing with native open-ocean species for limited resources – and in some cases, feeding on these open-ocean species.

Although more research is needed to understand how coastal species entering the high seas can impact native species, history shows that introducing invasive species can significantly impact endemic ecosystems, according to environmental scientists at Ocean Cleanup Matthias Egger.

Why is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch getting bigger?

Despite countries across the world remaining busy tackling plastic pollution entering the oceans, this may not be the full story of why plastic is growing so quickly in the Great Pacific Ocean Patch.

Instead, the scientists behind the new research emphasise the importance of intercepting and removing already-present plastics in the world’s oceans.

They hypothesise that garbage patches like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch are growing at such an unprecedented rate due to the accumulation of decades-old plastics breaking down into smaller fragments, rather than the new plastics entering the waters.

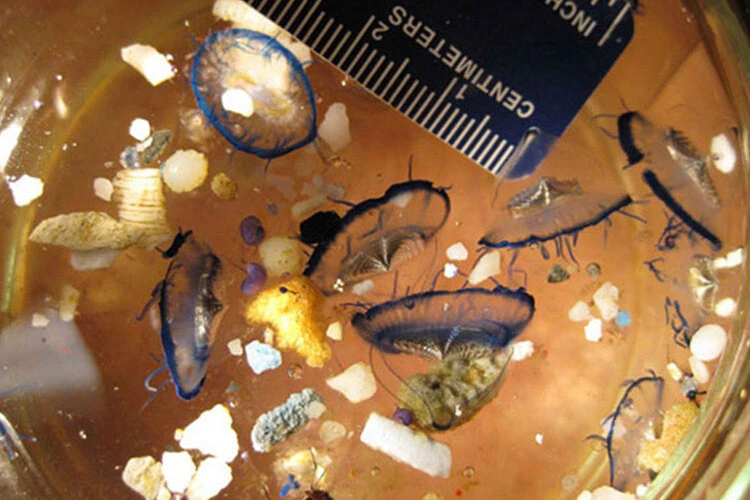

Scientists are also eager to point out that the accumulation of these plastics in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not akin to an ‘island’ of trash easily visible to the naked eye. Instead, much of this trash lies insidiously within the ocean waters, dispersed over vast surface areas that may be difficult to spot even if one were to sail directly through the garbage patch.

Ultimately, even if it isn’t obviously visible, marine pollution still poses a real threat to ecosystems and the future of many marine species alike.

‘Our findings should serve as an urgent call to action for lawmakers engaged in negotiating a global treaty to end plastic pollution,’ said lead author of the research Laurent Lebreton. ‘Now, more than ever, decisive and unified global intervention is essential.’