Despite the increasing risk of flooding, an increasing proportion of the world’s population lives on floodplains

By

The proportion of the world’s population that lives on floodplains is growing. In a study published in August 2021, researchers used NASA satellite data to map 913 large flood events which they compared with local population data. They found that the number of people in areas at risk of flooding had increased by 58-86 million between 2000 and 2015 – ten times what had previously been estimated.

Living on land that’s prone to flooding is nothing new; the earliest civilisations were built on floodplains. Cities flourished along the banks of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia (the name means ‘between rivers’), a region covering what is now Syria, Iraq and Kuwait. Crops were sown by Ancient Egyptians following the annual flooding of the Nile during the May-August monsoons, and China’s first dynasties emerged from the valley surrounding the Yellow River, considered the birthplace of Chinese culture and society.

The benefits of building on floodplains

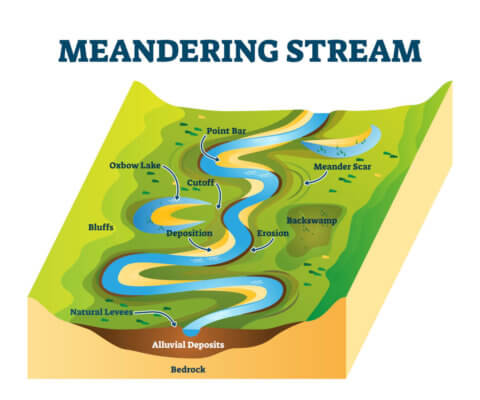

Floodplains are formed by the movement of rivers. As they flow and meander they erode the earth around them, over time creating a wide, flat valley on either side of their banks. When rivers burst their banks, they flow into this surrounding land.

Fluvial (river) flooding is caused by heavy rainfall or snowmelt, and changes in a river’s capacity. River waters carry materials such as clay, silt, sand and organic matter downstream; the Yellow River gets its name from the silt carried in its waters, giving it its yellowish-brown colour. These materials are then deposited as sediment along slower moving stretches – at bends or along the bottom of the river itself, decreasing its size and the amount of rainwater the river can accommodate, which increases the chance of flooding.

When rivers do flood, this sediment is spread across the floodplains. Nutrient-rich sediment creates fertile soils and, because they flood regularly, floodplains are naturally highly fertile. Flat and easy to farm, with a regular freshwater source, they make excellent agricultural land. The slow-flowing rivers also provide natural transportation networks, while roads and other infrastructure can be constructed across the level, surrounding area. This has historically made floodplains ideal sites for human settlement.

Irrigation and adaptation

Worldwide, population density in inland floodplains is now three times more than the global average. In the UK, a government flood risk assessment found that approximately a million people (in 542,000 properties) live in the floodplains of Greater London alone.

However, 84 per cent of those properties are in areas with a low risk of flooding. This is largely due to the construction of flood defenses, including the 520 metre-wide Thames Barrier, which spans the river estuary. It stands as high as a 5-storey building when its gates are closed, protecting the city from flooding caused by tidal surges during storms.

As better technology and techniques have developed, we have adapted to living in locations that flood. Ancient societies in Egypt and China dug irrigation canals into the floodplains to cultivate their crops. Villages and towns on land that flooded regularly, such as the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, built houses on stilts, floating houses or lived in house boats. When populations increased, cities erected barriers and dredged rivers to protect them and, with the intensification of agriculture, farmers have built and maintained levees to keep floods away altogether.

But intensive farming and, to a lesser extent, urbanisation have been cited as the key reasons for worsening flooding. In a 2017 report called the Changing Face of Floodplains, researchers at Salford University warned that 90 per cent of England’s floodplains no longer work as they should. Development and drainage have destroyed the ability of floodplains to act as natural flood barriers and store excess water. Instead, artificially smooth, uniform landscapes with little wetland or woodland result in towns and villages flooding more quickly.

Similarly, concrete and tarmac surfaces prevent rainwater from being absorbed by the ground. This causes water runoff that can overwhelm stormwater management systems, especially when local rivers are already full, leading to pluvial flooding.

Climate change

Climate change is already increasing the frequency and severity of floods as extreme weather events result in longer and more intense rainfall. In the Mekong Delta, elevated houses that have been adapted for seasonal flooding are no longer coping with new, higher water levels. In low-lying countries like Bangladesh, where 80 per cent of its territory lies on floodplains, sea level rise is causing more flooding and increasing the salinity of the rivers and groundwater, killing farmers’ crops.

In northern Europe, if high emissions remain unchecked and no further adaptations are made, damage from river flooding could triple by 2100. Despite this growing problem, demand for housing in some countries is driving development in areas where floods are a known threat. Since 2013, one in 10 of all new homes in England have been built on land at the greatest risk of flooding.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!