The multi-billion-pound shadow industry threatening marine life and exploiting human labour. But a new wave of surveillance is turning the tide…

By

Estimated to be worth anywhere from £7.8 billion to £18.5 billion, according to organised crime experts, illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing threatens the sustainability of fish populations, ecosystems and the livelihoods of legitimate fishers. Campaigners argue that without tackling IUU, there is little hope of securing sustainable long-term management of fish stocks.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

WWF International warns that seafood moves through a complex global supply chain that is weakly regulated and poorly enforced. This allows illegally caught fish to enter the market – and once mixed in, these products are difficult to trace.

Not only is IUU a key driver of global overfishing, says WWF, it’s ‘a threat to marine ecosystems, a risk to food security and regional stability, and an enabler of major human rights violations, including reports of bonded labour and slavery on larger vessels.’

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) describes slave labour in the fishing sector as ‘a severe problem’ and has reported illness, injury and psychological and sexual abuse. Bonded crew are vulnerable to mistreatment aboard vessels in remote areas of the sea, often for months or years at a time.

They are forced to work long hours for low pay in intense, hazardous conditions. The ILO says capture fisheries have one of the highest occupational fatality rates in the world and has called for greater efforts by flag states to ensure vessels under their registry comply with international and national labour laws.

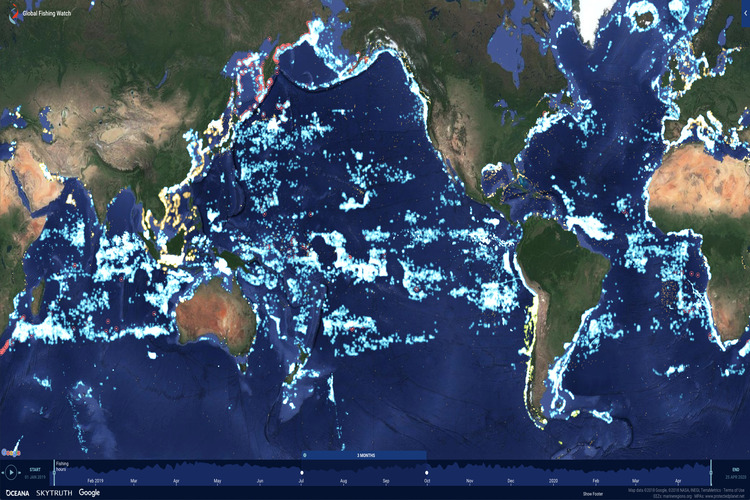

Global Fishing Watch believes technology is key to combating IUU. Tools such as automatic identification systems and vessel-monitoring systems have revolutionised enforcement efforts and given NGOs unprecedented visibility of what is happening at sea. ‘Transparency is the foundation of stewardship,’ says Tony Long, chief executive of Global Fishing Watch. ‘We believe a visible ocean is a protected one.’

Over the past decade, there have been major gains. ‘In 2012, barely a sliver of the global fleet shared its position via public channels. Today, nearly 140,000 vessels

– roughly one-third of the world’s large fishing fleet – transmit their movements through vessel monitoring systems,’ says Long.

Global Fishing Watch says its platforms now track 40 million square kilometres of ocean and, in the first quarter of 2025, triggered action against more than 600 vessels – including some operating in previously inaccessible parts of the ocean. ‘Our tools are being used consistently by over 400 government agencies, 260 research institutions, nearly 200 NGOs and dozens of media outlets,’ he adds.

These developments offer hope that, with sustained investment and cooperation, fish stocks can be managed sustainably. ‘I am cautious – but I am optimistic,’

Long says. Governments, researchers, civil society and journalists are increasingly able to map fishing activity with unprecedented accuracy.

‘Regional fisheries management organisations are using this data to inform better policy,’ says Long, ‘but must commit to using these tools at scale.’