For years, conflicts have plagued nations bordering the Sahara Desert. But what exactly are the causes of the Sahel’s struggles?

By

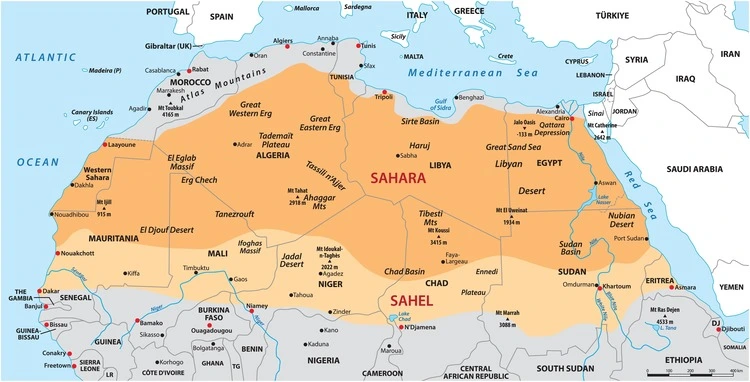

Twenty-four million. That’s the number of people that require assistance of some kind in the Sahel, the semi-arid region that borders the vast plains of the Sahara Desert. Spanning from Senegal to Eritrea, the Sahel has long been the location of numerous conflicts, humanitarian crises and security issues.

With more than 4.9 million of these people officially displaced, and 870,000 refugees, it is clear the region’s tumultuous present and past cast devastating effects upon those who live there.

As we look toward the conflicts that mar the Sahel today, it is clear that complex and interwoven factors contribute to all their causes, making it increasingly difficult to curb them and their effects.

Extremism in the Sahel

One of the major crises to hit the Sahel in modern history is that of violent extremism, and the subsequent conflicts it causes. So significant is its impact upon the region that the Sahel accounts for almost half of all global deaths by terrorism.

With the collapse of counterterrorism support and weakening regional leadership, violent extremism is able to take hold in the vacuum that remains in the Sahel, by groups including Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Islamic State in the West African Province (ISWAP).

Attacks on hotels in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Ivory Coast in 2015 and 2016 – as well as other major attacks on cities including Markoye in Burkina Faso – highlight the threat of terrorism in the the region. In recent times, JNIM has gained control over territory in northern and central Mali, whereas ISGS carry out operations in northern Burkina Faso due to clashes with JNIM from 2020.

Such a widespread expansion of violent extremism cannot be pinpointed to one cause. A web of factors, from weak governance due to corruption, to human rights violations and frequent transfers of power all combine to create conditions hospitable for violent extremism to grow.

Rural northern regions in the Sahel tend to remain underdeveloped compared to their southern counterparts, again making it likely for extremism to proliferate.

The very landscape of the Sahel also makes it vulnerable to violent extremism. Its wide expanse of ungoverned spaces – particularly forested areas – inadvertently allow criminal gangs to hide and carry out illegal activities. For example, in Nigeria, the Sambisa, Falgore, and Ajjah forests have been used by Boko Haram to plan and launch attacks. National parks, such as the W Park in West Africa, have long been abandoned by governments and are instead used by terrorist organisations as a base.

Trafficking and smuggling networks in the Sahara-Sahel region

Drug trafficking in the Sahel is a common occurrence, with illegal substances, including cocaine, cannabis and opioids, transported by criminal networks more easily than ever, according to a 2024 UN report.

Seizures of cocaine in the Sahel rocketed from an average of 13kg per year between 2015 and 2020 to 1,466kg in 2022, highlighting the exponential growth of illegal trade in the region.

The location of the Sahel makes it an ideal stopping point on trafficking routes from South America to Europe but it threatens the stability of the region’s economy and security while also impacting public health.

Read more on the Sahara-Sahel region…

- Will Africa’s Great Green Wall ever be finished?

- Sahel heatwave impossible without human-caused climate change

- Geo explainer: Will the Sahara flood again?

Unsurprisingly, drug trafficking and terrorism in the region are inextricably linked. The money earned via illegal operations like drug trafficking ends up with armed groups in the region –including Plateforme des mouvements du 14 juin 2014 d’Alger (Plateforme) in Algeria and Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) in Mali. This money is then used to purchase weapons and finance any further operations, further perpetuating an unceasing cycle of violence and drug trafficking.

As a result of a plethora of factors, from economic uncertainty to violence and conflicts in the region, human smuggling is also another issue that the Sahel faces. Due to increased surveillance of previously-used smuggling routes, counter-smuggling efforts have diversified across often unsafe routes to evade being caught.

Many of those who embark on migration journeys through the central Sahel are, therefore, exposed to greater danger, such as trafficking and gender-based violence. In some cases, deadly disasters can occur when migrants flee in smuggling activities, such as the shipwreck of the coast of Greece which killed at least 79 men, women and children.

The disputed Western Sahara territory

One of the most long-standing conflicts in the Sahel region is over the territory of the Western Sahara. Since 1975, the region has been disputed between Morocco and the Indigenous Sahrawi people, led by the Polisario Front. After a 16-year guerrilla war between both parties, a ceasefire led to 20 per cent of the territory being controlled by the Polisario and the rest by Morocco.

In 2020, this ceasefire collapsed, with the Trump administration then officially recognising Moroccan sovereignty over the territory.

Discover more about the Western Sahara conflict:

The United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established in 1991 to monitor the post-conflict situation and to help a referendum on the matter. This process has been underway since and an agreement over the territory has yet to be made. Since 2003, Morocco has refused to take part in any referendum which includes an option for Western Sahara to be independent.

Sudan Civil War

In the Sahel lies another conflict, also considered the world’s worst displacement crisis: the Sudan Civil War. Beginning in April 2023 due to fighting between rival factions of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), more than 8.2 million people have since been displaced and at least 15,000 people killed. The war continues as both parties fight for control of the state and its resources.

More on Sudan:

- Refugees from Sudan’s bitter civil war are stretching the aid agencies to breaking point

- Surviving the floods of South Sudan

As those displaced move into nearby countries such as Chad, Niger and Eritrea which are also unstable, the situation becomes even more concerning. Although the UN Security Council passed a resolution calling to cease conflict in March 2024, there has been no ceasefire in the region, exposing more civilians to danger.

The intensity of violence has made it difficult for humanitarian aid to reach the areas it needs to – particularly the South of Sudan – with looting of businesses, humanitarian aid warehouses and markets only further exacerbating food shortages in the country.

Even before the war, Sudan was facing a humanitarian crisis due to extreme weather shocks, as well as social and political unrest.

Mali Civil War

Insurgencies in both north and central Mali have occurred since 2012, and this year, fighting resumed between the Malian army and a coalition of armed groups who had previously signed a peace agreement back in 2015.

The human rights of civilians in Mali have significantly deteriorated in recent years due to attacks by Islamist armed groups linked to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS).

Further monitoring of human rights has also been marred by the government’s request to the UN’s Security Council to withdraw a peacekeeping mission to Mali. The absence of such a mission may now expose civilians in northern and central Mali to further unrest and violence.

Other countries have stepped into the conflict in Mali. The G5 Sahel – a regional partnership between Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger – have contributed a force of 5,000 troops, along with a pledge from the African Union to deploy several thousand more.

France, too, ran a counterterrorism operation in Mali – known as Operation Barkhane – comprising almost 5,000 French troops and costing more than $1 billion each year. In 2022, the troops were withdrawn by France, and Mali’s government has strengthened its ties with Moscow.

In the same year, mercenaries from the Wagner group were deployed in Mali, a decision that has been condemned by the United States and other European countries.

What is being done to help the Sahel?

Several organisations are providing support to those in need within the Sahel. The EU is one of the largest donors of humanitarian aid to the region. In 2024 so far, it has donated €144 million, which is used to provide shelter, treatment for malnourished children and emergency food assistance among other protection.

Another key support is the UN Refugee Agency, which, along with providing emergency shelter and relief items to civilians, is also giving psychological support to victims of sexual and gender-based violence in the Sahel. The organisation is also working with the governments of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger to create the Bamako Process, a platform between governments that seeks to strengthen security of vulnerable populations in the region.

A wider plan adopted by the UN is also underway – the UN Support Plan for the Sahel – in order to accelerate peace and ensure economic growth. With 64.5 per cent of the region’s population under the age of 25, the Sahel has one of the world’s youngest regions.

Coupled with this, its location on top of the largest aquifers on the continent – as well as being a prime candidate for solar energy production – means there is vast opportunity to grow its natural resources sector with the support of the UN’s plan.