Photographer Peter Caton has been in the region in recent months, documenting conditions and the stories of those arriving

At the Renk transit centre in South Sudan, aid agencies are working flat out in impossible conditions. High numbers of refugees from Sudan are arriving – the highest numbers since the Sudanese conflict began last April. Many have travelled for days on foot without enough food and water, and with only the belongings they can carry. ‘The humanitarian situation is spiralling out of control,’ says Mark Atterton, regional director at international non-profit Relief International. ‘We are imploring the international community to take action.’

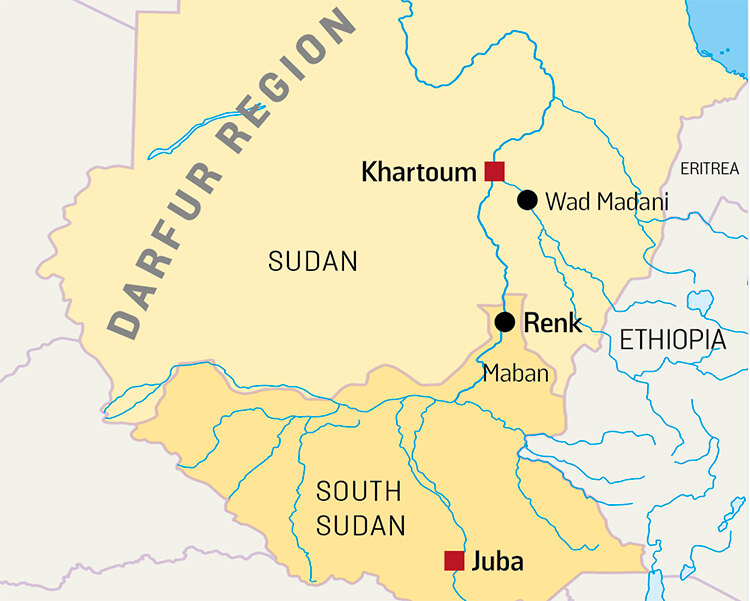

Fought principally between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the brutal Sudanese civil war has been raging for a year, during which there has been direct fighting in the capital Khartoum, in Darfur and in other parts of the country. The RSF has been accused of atrocities against civilians, including killing, rape and pillaging, while SAF aircraft have bombed civilian targets and critical infrastructure.

More than 80 per cent of arrivals in South Sudan are returnees: people who fled South Sudan and its long history of conflict, only to face doing it all over again in the other direction. From the UN-run Renk transit centre, these refugees make the nine- to ten-hour journey to Maban in Upper Nile State, where there are four refugee camps. More than 20,000 people have arrived in Maban to date and the number has been increasing since late November.

The conflict in Sudan began a year ago. Now, the number of people arriving in South Sudan is surging and aid is running perilously low. The arrivals are putting further strain on an already overburdened health system. There’s an estimated ratio of one physician for every 65,574 people in the country and 9.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection.

Both Relief International and independent development and humanitarian organisation Plan International are on the scene. Tragically, however, humanitarian organisations are now having to downsize projects or end them altogether due to a lack of funding. The UN’s Regional Refugee Response Plan was only 35 per cent funded in 2023 and the UN has just launched its 2024 response plan appealing for more support.

The number of people fleeing to South Sudan peaked at nearly 72,000 in December and almost 68,000 in January. Most returnees and refugees are arriving in South Sudan via the Joda border crossing. Many have travelled for days on foot without enough to eat or drink. According to the World Food Programme, 90 per cent of families say they are going multiple days without eating.

Renk Transit Centre is under immense strain. Originally intended to host up to 4,000 people, there are now more than 23,000 sheltering there. Relief International workers are treating infections, providing vaccines and supporting people who are severely malnourished. In December, eight children were confirmed to have contracted schistosomiasis, an infection caused by a parasitic worm found in water. Relief International is working with the WHO to facilitate the transportation of Praziquantel tablets to treat the infection.

Plan International operates a child-friendly space in Renk. The organisation is particularly concerned about the situation for single women, adolescent girls, unaccompanied children and single-female-headed households. It says that multiple deaths have been recorded due to a lack of adequate health services, specifically for women in cases of gender-based violence and pregnancy. Meanwhile, Relief International midwives are supporting the delivery of babies at the transit centre.

Refugees arrive in Renk from the Sudan border on trucks loaded with whatever possessions they could gather before fleeing the violence. The transit centre is overcrowded and the current user-to-latrine ratio is 200:1, ten times the recommended ratio of 20:1. Due to this severe overcrowding and inadequate sanitation, the risk of a cholera outbreak is high.

Relief International staff are kept busy conducting around 250 consultations every day at the health clinic at the transit centre. Plan International is providing child protection and psycho-social support to children who’ve experienced trauma as a result of the conflict.

South Sudanese returnees are packed onto a boat to begin the long journey from Renk transit centre along the White Nile to Malakal. From there, many will be flown to the capital, Juba. The journey from Renk to Malakal takes between two to three days.

When Dewi Osman’s family fled, he stayed behind in Sudan to gather what little crops they had left. During his journey to rejoin his family, Dewi could not light fires to cook for fear of drawing attention to himself. He became so weak that he was unable to carry the crops and was forced to leave them on the roadside. This photograph was taken on the day on which he was reunited with his two children at Maban’s Doro Camp.

VITAL SEED BANK AT RISK

Bryony Cottam reports

In December, the RSF, the key belligerent against the Sudanese government armed forces in the war, seized the city of Wad Madani, 150 kilometres south of Khartoum, forcing hundreds of thousands to flee. Amid the chaos, homes and businesses were ransacked by looters. Mohammed Elsafy, a Sudanese plant geneticist working at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, began to hear reports from the national seed gene bank on the outskirts of the city, where Sudan’s seed collection is housed. ‘They told me that the freezers used to store the seeds had been stolen,’ he says.

Since 1982, researchers at the Agricultural Plant Genetic Resources Conservation and Research Centre in Wad Madani have amassed an estimated 17,000 accessions (seeds, tissue and DNA sequences) from wild plant species and crops grown all over Sudan. It’s one of an estimated 1,500 seed banks around the world, where material is stored to preserve the genetic diversity of plants. ‘Sudan is a centre of origin for many crops, including sorghum, sesame, millet and several species of melon,’ says Elsafy, ‘so this is an important seed bank for Africa.’

Only 17 per cent of Sudan’s seeds have been safely duplicated in foreign seeds banks, leaving more than 80 per cent of the collection at risk of being lost. When he first heard that the freezers had been looted, Elsafy tried to contact the RSF leader, ‘just to explain to them that this is not about the conflict, this is something we need to take care of for all Sudanese people’. While the seeds remain sealed in their aluminium bags, they should survive for several more months, but Elsafy doesn’t know the conditions inside the facility and fears the worst.

Typically, seeds and other genetic material are stored at -20°C; at this temperature the seeds can remain viable for hundreds or even thousands of years. However, Elsafy says that even for short-term storage, samples should be kept below -5°C. ‘At the moment, without the freezers, the temperature in Sudan is almost 45°C.’

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization secured a building in Port Sudan (670 kilometres east of Khartoum) to temporarily house the seeds, but talks have broken down between the organisation and the Sudanese government on how to get the seeds to safety.