Andrew Brooks asks whether the lessons learned from a mass 1930s trespass should be applied to today’s environmental protests

In the summer, I had two memorable holidays. The first was to the Peak District and the other to Cologne. As a child, I often visited Derbyshire, but it had been more than two decades since I had spent time in Britain’s oldest national park.

The landscape has changed. Beneath my feet, there was the same course of sandstone; around me, familiar watercourses such as the River Derwent and Padley Gorge. Stands of ancient forest, fringed with thick bracken, still populated the valleys’ sides. Where the geology meets the horizon, the environment maintained its most iconic features: the Dark Peak escarpments of Froggatt and Curbar Edge.

The physical geography was as I had remembered it. In the built environment, there were changes – more holiday homes, tea shops and outdoor clothing stores – but the real shift was in the people; the cultural landscape was transformed.

Visitor numbers were greater, and the crowds were more diverse. Walking up from Grindleford Station through the woods, I passed hikers heading in the opposite direction, who, in their ages and varied backgrounds, truly reflected a cross-section of the UK’s population.

Out into the open, there were multi-generational Asian families picnicking; groups of young climbers making their way to the rock faces, as diverse as the students of nearby Sheffield; and same-sex couples hand-in-hand. That this population was representative of modern Britain doesn’t seem remarkable today, but the visibility of all of society in this national park contrasts with my memories of a space that I thought of in the late 20th century as socially conservative, primarily white and very middle class.

This increasing democratisation of the Peak District is entirely in keeping with the fight to found one of the world’s first national parks that began a century ago.

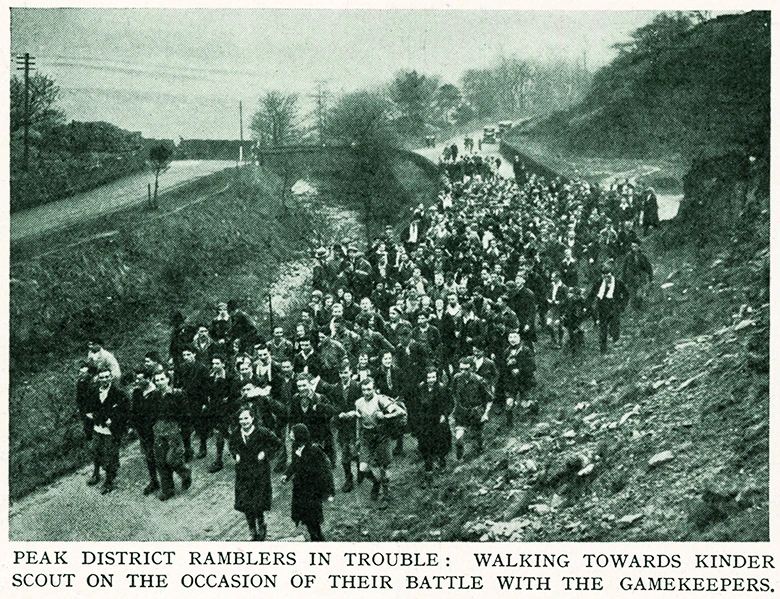

The Peak District was formerly a private rather than a public space. In 1932, there was a mass trespass of 400 people of the Kinder Scout plateau. Converging from Manchester in the west and Sheffield in the east, they wanted to temporarily escape their cities, the brick terraces and smokestacks, fill their lungs with fresh air and open their eyes to awe-inspiring hills and greenery.

As Benny Rothman, who at 20 years old was one of the leaders of the rebellion, later recalled that it was a colourful moment: ‘There were hundreds of young men and women, lads and girls, in their picturesque rambling gear: shorts of every length and colour, flannels and breeches, even overalls, vivid colours and drab khaki… multi- coloured sweaters and pullovers, army packs and rucksacks of every size and shape.’

More from Andrew Brookes…

Alongside Rothman, four other participants were found guilty of riot and received punishments of between two and six months in prison. While they may have lost the day, they helped shift attitudes towards the natural environment and their brave actions are now widely celebrated for catalysing the establishment of the Peak District. It became the UK’s first national park on 17 April 1951.

Turning to my second holiday, as I was preparing for my trip to Germany, I was alarmed to read that young protesters had glued themselves to the runway at Cologne-Bonn Airport.

They were five members of the Last Generation activist group, part of coordinated action across Europe, including comrades in Finland, Norway, Spain and Switzerland, that called on governments ‘to stop extracting and burning oil, gas and coal by 2030 as well as supporting and financing poorer countries to make a fast, fair, and just transition’.

The disruption only lasted a day and my flight went ahead as planned. I had a great holiday in the Rhineland – an underrated tourist destination – but at the time, I’d been frustrated that I would have to cancel my trip. Was I now the conservative reactionary?

In the UK, similar protests have blocked motorways and runways and led to protesters receiving custodial sentences of up to four years. When I stop and consider this turn of events, my own view is that while I wouldn’t participate in these acts myself, I vehemently believe the harsh punishments handed down to protesters who are motivated to preserve the environment are completely disproportionate.

How different is what they are doing today to Benny Rothman’s and his pals’ actions last century?

One of my summer holidays was enabled by environmental activism long ago and the other was almost blocked by a contemporary movement. By placing these two protests beside one another, this long view might help us reconsider why passionate people in Generation Z are at the vanguard of trying to make the world a better place.

Rather than locking them up, we need to involve them in discussing how we can democratise the environment.

Next summer, if my travel plans are disrupted, perhaps I will make a trip to another one of Britain’s national parks and be thankful for the bravery of previous generations of protesters, and try to listen to the arguments of today’s environmental activists.