Jules Stewart reviews Geographical’s book of the month, Our Bodies, Our Planet, by Marcus Hall – available to buy now

By

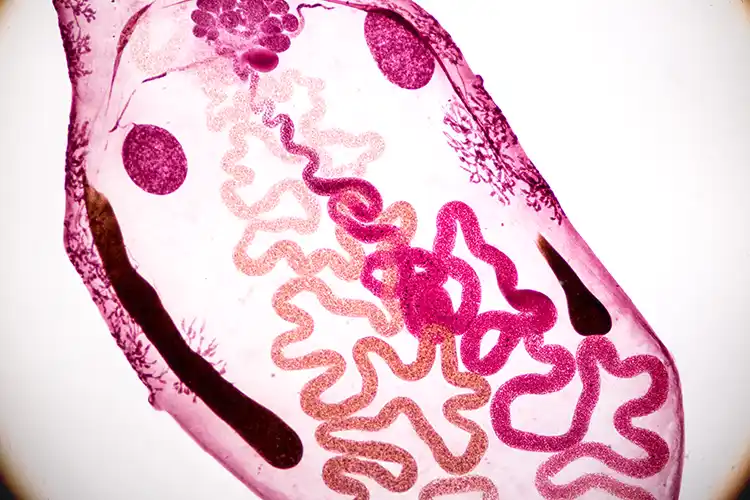

The science of parasitology has demonstrated its relevance to human health, agricultural production, wildlife management and almost every other field linked to the life sciences. In our fundamental activities of breathing and sleeping, eating and digesting, reproducing and ageing, our bodily creatures are interacting with us and with each other.

Marcus Hall argues that parasites and parasitic relationships are fundamental and vital to life on Earth. The author maintains that, unlike harmful pathogens, parasites may cause no ill effects and may even improve our well-being and the lives of the creatures around us. ‘Our understanding of a parasite can be elusive,’ Hall says.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Some parasitologists assume that parasites are simply creatures that take more than they receive and so damage their host. Others counter that many parasites are maligned and misunderstood, and if they cause damage or disease, such activities are merely temporary distractions in a parasite’s march towards becoming a cooperative and healthy partner with its host.

Malaria therapy is an example of how a microbe can counteract the negative effects of another microbe or even provide curative benefits. Humans, intentionally or accidentally, ingest or absorb a range of organisms that can offer health benefits beyond inducing fever.

A physician may prescribe capsules of ‘probiotics’ or even faecal transplants to a patient who has undergone repeated treatments of antibiotics to help replenish that patient’s intestinal biodiversity. There is also evidence for the advantages of so-called cross-immunities, whereby exposure to one pathogen confers partial or full resistance to another.

One of the central mysteries of the deadly and misnamed Spanish flu epidemic of 1918–20 is that young adults in their 20s and 30s were especially susceptible to the disease; the elderly are typically much more vulnerable to such viruses. Instead of pointing the finger at the Spanish flu’s unusual pathogenesis, epidemiologists have uncovered evidence of similar, though milder, strains of this virus that swept the world two generations earlier, thereby conferring immunity protection on those born before 1880. Since people born after this date weren’t exposed to these strains, they missed out on acquiring the crucial immunities.

Can our microbial symbionts provide some of us with the advantages of ‘herd immunity’, which protects a minority of individuals if a majority of hosts have already been infected? Hall quotes the cautionary tale of those who contracted polio as young adults because improvements in sanitation meant that they weren’t exposed as infants to the polio virus, which could have been neutralised with maternal antibodies. Much like Spanish flu victims, those polio victims who waited to confront a dangerous virus later in life would eventually suffer even more severe consequences.

All these examples illustrate how factors such as the timing of parasite exposure, the size and distribution of the host population, and the degree of genetic relatedness between parasites can be crucial in determining how far one can benefit from one’s parasites. One must remember that it’s in the parasite’s best interest to make sure that its host ultimately survives, thrives and goes forth to multiply.

Parasitism is a phenomenon of partnership, and the association of parasite and host has had far-ranging cultural, biological and possibly geophysical consequences. Most of us are instinctively repulsed by these little freeloaders, but Hall highlights the collateral effects they have on our lifestyles and imaginations.

Do we disregard our parasites at our peril, the author asks? Instead of viewing these intimate creatures simply as pathogens that produce disease, he concludes that many parasites can be re-envisioned as cooperators and symbionts. Humans and their army of parasites march together down life’s path, often to the benefit of each other.