Doug Specht and Sarah Capes examine how Indigenous voices have struggled to be heard at COPs – until now

The organisation of COP30 has posed extraordinary challenges from the outset. Belém, tucked deep in the Amazon, ill-equipped for the arrival of tens of thousands of global delegates.

Basic infrastructure struggled to keep pace: accommodation, transportation, catering, and even sanitation all proved to be harder to get ready than anticipated.

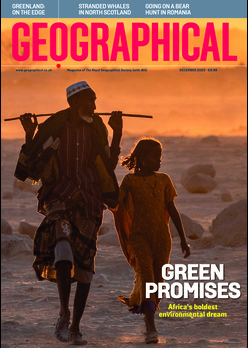

Yet, as Brazil’s President Lula remarked during the opening, perhaps these constraints are wholly appropriate. COP30 is designed to bring the conference, literally and symbolically, back down to earth. This city, surrounded by Amazon forests and waters, faces the urgent reality that ‘climate change is not a future threat but is already a tragedy playing out in the present,’ to quote Lula’s opening words at the event.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Recent COPs have landed in settings far removed from the gritty immediacy of climate impact. Sharm El Sheikh, Dubai, and Baku, each a hub for fossil fuel economies and international business, have offered up their coastal luxury and strategic positioning to market themselves as epicentres of innovation, finance, and future-facing development.

These venues, replete with comfort and spectacle, placed COP at a considerable remove from those whose lives most directly intersect with the changing climate. Lula’s vision for COP30 is a striking departure. The Brazilian president insisted on a summit shaped by local people, their traditions, and their foods, staging what has been hailed as ‘the COP of the people’ and, crucially, an Indigenous COP.

The impact is immediately apparent in the sheer scale and presence of the Indigenous caucus. At this summit, the number of Indigenous participants dwarfs previous years. Their presence is far from symbolic: Indigenous peoples occupy every corner of COP, attending as experts and as rights-holders. Their testimonies speak to the slow, relentless violence of ecological change, the devastation unleashed by extreme events, and the persistent injustices of poorly planned, so-called climate ‘solutions’. Yet, they also bring vital strategies, grounded in Indigenous knowledges and technologies, for mitigation, adaptation, and resilience-building.

And still, the story so far is one of persistent marginalisation. The UN’s endorsement of Indigenous peoples as an official constituency in theory rarely translates into impact when the decisions of COP are carved out in practice.

Too often, their distinct collective rights, outlined in international agreements such as UNDRIP and the Paris Agreement, are lost among the welter of other interests, private sector, finance, youth, local governments, and vulnerable communities. At COP28, references to Indigenous rights appeared only in generic introductions, buried deep within paragraphs copied from previous agreements, and were notably absent when it came to the central rules and guidelines on climate action and finance.

A critical point of difference, and one frequently misunderstood, lies in the approach to the natural world. Where mainstream climate conversations often reduce landscapes and ecologies to resources for human use, the relationship between Indigenous communities and their environments has always been one of reciprocity and respect. These relationships go beyond survival: drawing from their environment for food, water, shelter, transport, and medicine, they return a reciprocal care that safeguards the well-being of both people and place.

Even where environmental degradation has made traditional ways difficult or impossible, the underlying ethos remains: the future of people is inseparable from the future of the land. This sense of connection, at once deeply practical and profoundly philosophical, is largely missing from the hermetically sealed spaces in which much of COP is conducted.

During COP28 in Dubai, several Indigenous delegates raised to the author the question of how one could ‘feel’ the climate crisis through air-conditioned meeting rooms and windowless conference halls. How could delegates truly grapple with the scale of environmental loss when ensconced in man-made landscapes where even the grass is plastic, and the sun and water exist as little more than materials for technological “solutions”? How can the world’s most powerful decision-makers, cut off in climate-controlled offices, hope to lead on something they experience only in the abstract?

President Lula’s own opening statement at COP30 echoed this reflection. Quoting Yanomami Shaman Davi Kopenawa, he warned that city thinking is clouded by the smoke and noise of machines. Lula underscored the centrality of Indigenous territories to genuine climate change mitigation and expressed the hope that simply being in the Amazon, surrounded by the complexity and calm of the forest, would inspire the new clarity and humility necessary to recognise both the inequalities and urgency of the crisis. In Belém, the city itself still incomplete, the daily realities of climate and community cannot be shut out.

This year has brought a convergence both geographical and symbolic. The region is home to millions of Indigenous people and hundreds of distinct peoples The waterways that thread through the Amazon shaped the journeys of hundreds of delegates, many arriving after weeks of travel. They came together not just to bear witness, but to strategise and build solidarity, their very journey a statement about enduring presence and continuing agency.

At the opening plenary, the Indigenous caucus set out its demands with directness and precision. International human rights standards, including UNDRIP, must be protected within all aspects of climate transition, and this includes explicit recognition and safeguarding of Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation and Initial Contact, as well as redress for the impacts of extractive, unsustainable economic practices.

All frameworks for climate finance should ensure direct, flexible, and culturally appropriate access, which means a recognition of indigenous financial mechanisms and the ability to make autonomous decisions about expenditure and investment. There must be full representation at every stage of decision-making, from national plans to international actions, alongside legal guarantees protecting territory, governance, and knowledge.

Moreover, this participation needs to not end at the point of being listened to, but must ensure that these interventions are truly heard and contributions taken into account in decision making. Crucially, the roles of Indigenous women, youth, and persons with disabilities must also be acknowledged: participation must be real and meaningful, not notional.

None of these asks are radical. Everything requested here exists already in the language of international agreements, but their actualisation remains elusive. What the Indigenous caucus is asking for is not new promises but delivery on old ones, and a profoundly practical engagement with the experience and expertise that they alone bring.

Does COP30 mark a genuine step-change? There is a sense, emerging from the city’s climate, its rivers and forests, its unavoidable proximity to nature, that this could be a different sort of summit.

This time, perhaps, the unique perspectives and voices of Indigenous peoples will echo not only in the theatrical spaces of plenary but in the final documents, the rules, and the funding flows that make COP decisions real. The crisis is not abstract; the Amazon and its peoples, so often erased in international debate, are finally impossible to ignore. If hope is a fragile resource, it is one that COP30, rooted in the Amazon, may nurture in a way that previous conferences could not.

Ultimately, climate action is not a technical fix, but a question of how people and places exist together. The challenge now is to turn recognition into reality and to ground the future of climate policy in the lived wisdom of those who have lived with the forest the longest.