Rory Walsh revisits Victorian Manchester, where a booming cotton industry is world-famous, but life expectancy is just 26

Discovering Britain

Walk • Urban • North West England • 3 Miles • Web guide

Until recently, the Charter Street Ragged School seemed a lonely building. Its darkened windows faced a scrubland car park. Today its redbrick walls are literally overlooked by towers of gleaming glass. The Gate and the Stile are two of four planned blocks in the MeadowSide development. MeadowSide is part of Noma, which at £800million and 20 acres is the largest regeneration project in North West England. Upon completion MeadowSide is set to create 756 new homes, including luxury penthouses.

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

Tucked below them, Charter Street Ragged School is an orphan of another age. It opened in 1866 to give ‘religious instruction to children of the poorest classes.’ The school’s remit included providing pupils with food and clothes. Across the road, future MeadowSide tenants will have exclusive use of a private gym. While some Discovering Britain walks visit landscapes unchanged for millennia, others don’t.

Cities change fastest of all but few keep pace with Manchester. ‘Lockdown was interesting,’ says Dr Angela Connelly, this walk’s creator. ‘I didn’t go into the city for 18 months. When I went back, whole areas were unrecognisable. There was so much development.’ Connelly moved to Manchester from her native Scotland almost twenty years ago. As senior lecturer in the School of Architecture at Manchester Metropolitan University, she keenly observes the city’s skyline. ‘Manchester feels more gentrified but the real change is the density. Not just more skyscrapers, there’s more people too.’

Manchester has been transformed before. ‘What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow,’ observed Victorian prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. The revolution that turned this small mill town into the world’s first industrial city is a well-known tale.‘The narrative around Manchester is always about economic miracles and constant evolution,’ says Connelly. ‘I wanted to show the other side of the story, the one that’s often forgotten about.’

In Victorian Manchester, beside extreme wealth was extreme poverty. Slums, disease, illiteracy, alcoholism, child labour. In 1840 residents had an average life expectancy of 26. Connelly’s walk explores why and uncovers some of the organisations who helped the city’s poorest people. The route circles Ancoats and the north of the city centre. The area, part of the vibrant Northern Quarter, is packed with independent shops, cafes and galleries. Connelly recalls the sites and sights being rather different. ‘Ancoats is thriving now but ten years ago, much of it was derelict. I remember winter days, all foggy and cold, when it felt like a Victorian ghost town.’

Despite the exorcisms of regeneration, these 19th century spirits can still be found. Some places are more haunted than others. The MeadowSide blocks border the largest green space in central Manchester, Angel Meadow. During the Covid-19 lockdowns, this popular urban park was an invaluable oasis of fresh air. It wasn’t always so sweet. ‘The park was a paupers’ burial ground,’ Connelly explains. ‘There are thought to be 40,000 people under here.’

Their bodies were placed in a large pit, which was covered with wooden boards each night to deter rats. When the ground was full, Angel Meadow became a notorious gambling den. In the 1820s, people began digging up the soil and selling it as fertiliser. To stop them, the site was paved with flagstones. Later, a children’s playground was built on top. Standing on the flags today it’s incredibly sobering to imagine what lies beneath our feet.

Although some of the content is upsetting, the walk is ultimately uplifting. Connelly continues; ‘Many religious and charitable groups were appalled by working-class living conditions. So, they tried to help. In the era before the Welfare State and government support, these groups could be the difference between life and death.’ At the forefront were non-Conformist churches, especially Methodists. Connelly’s walk evolved from her research into Manchester’s Methodist Halls. ‘I was drawn to them as social locations,’ explains Connelly. ‘Methodists used their Halls to engage with the working classes, ultimately to disseminate their religious beliefs. As a result, the Halls were designed in ways that would encourage the most visitors.’ From Angel Meadow, the walk visits several non-Conformist buildings of the period.

On Great Ancoats Street, the Methodist Women’s Home and Night Shelter provided accommodation for ‘fallen women’. The ground floor had a coffee tavern, an alcohol-free place to socialise away from men. Though built to uphold the Victorian ideal of maintaining ‘separate spheres’ between the sexes, the tavern is an ancestor of today’s café culture. On Peter Street, the impressive St George’s House was built for the YMCA. The building’s tiled façade originally included a members’ swimming pool and a gym. Connelly summarises, ‘They were multi-purpose venues, way ahead of their time. They could be regarded as the forerunners to modern mixed-use developments.’

At its height, the Manchester and Salford Methodist Mission had ten Halls in the city. Past the Arndale Centre, Connelly points out what appears to be an ordinary group of shops on Oldham Street. Above and behind them is the first Methodist Central Hall built in the UK. It was deliberately designed to not look like a church. Even the shops were part of the original building. ‘Besides drawing in visitors, letting out shops on the ground floor helped to pay for the Hall’s upkeep,’ Connelly explains. ‘Many non-Conformists combined charity with ruthless business sense. They were hard-headed as well as warm-hearted.’

DISCOVER MORE OF BRITAIN

One of Connelly’s favourite spots is the Albert Hall, ‘When I first researched the walk, it was empty. Now it’s a successful music venue.’ Fittingly so. Many Methodist social events included choir and band concerts, with programmes inspired by music hall entertainment. During the Second World War, the Albert Hall’s 2,000- seat main hall became the temporary home of the Halle Orchestra. The huge baroque building remains an impressive reminder of how influential Manchester’s Methodists were.

By 1945, there were almost 100 Methodist Central Halls in the UK. Today there are less than 20. Many have disappeared or changed use. The walk’s themes however are unchanged. The route concludes at Manchester Cathedral. Before then, we turn off Deansgate to stop outside the Wood Street Mission. Founded in 1869 to aid destitute children, Wood Street Mission endures today as a charity. They provide low-income families with clothes, books, and toiletries.

The Wood Street Mission’s ongoing presence highlights an unsettling parallel with the Victorian city of Connelly’s walk. Modern Britain’s ‘gig economy’ and ‘dark kitchens’ have a distinctly Victorian feel. As do increases in homelessness and reliance on food banks. Connelly suggests, ‘There is this sense that the Welfare State has shrunk again in recent years, and that volunteers and charities are stepping in to fill the gap.’ And the gap is widening. Research suggests that the disparity between Britain’s poorest and wealthiest has increased since the start of the pandemic. So, the Mission continues.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

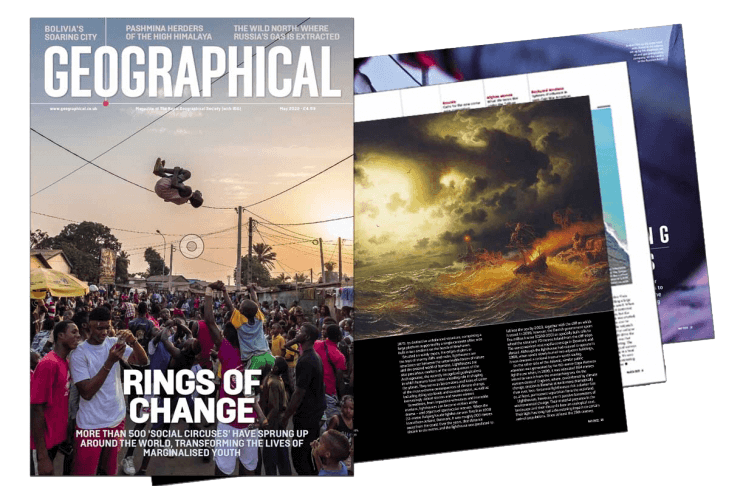

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

Go to the Discovering Britain website to find more hikes, short walks, or viewing points. Every landscape has a story to tell!