Rory Walsh explores working life and landscape art in a picturesque Kent valley

Walk • Rural • South East England • Web Guide

Standing at the rim of the Darent Valley feels like gazing at a huge painting. The view could be a scene by Constable, Ravilious or Paul Nash. A blanket blue sky tops a rolling quilt of green fields. Between rows of hedges and clumps of trees, a church tower rises over the pretty village of Shoreham. Small black and white dots – cows and sheep – speckle the valley floor either side of a meandering river. In the foreground, spread out upon the grass, is a large white cross. On a sunny Good Friday morning, it seems a fitting place to be.

Suddenly, through the chattering birdsong, there’s a low, buzzing growl. To the left, another cross appears in the air – dark this time. Within seconds a Spitfire roars overhead. ‘They fly out from Biggin Hill airfield and use Shoreham Cross to navigate,’ explains William Alexander, a fourth-generation local farmer and creator of this walk. The stirring spectacle is also a poignant reminder. ‘During the Second World War, the Darent Valley was Britain’s most-bombed parish. German pilots flew towards East London over Kent. If they didn’t drop all their bombs, they would turn around and release them here to speed back.’

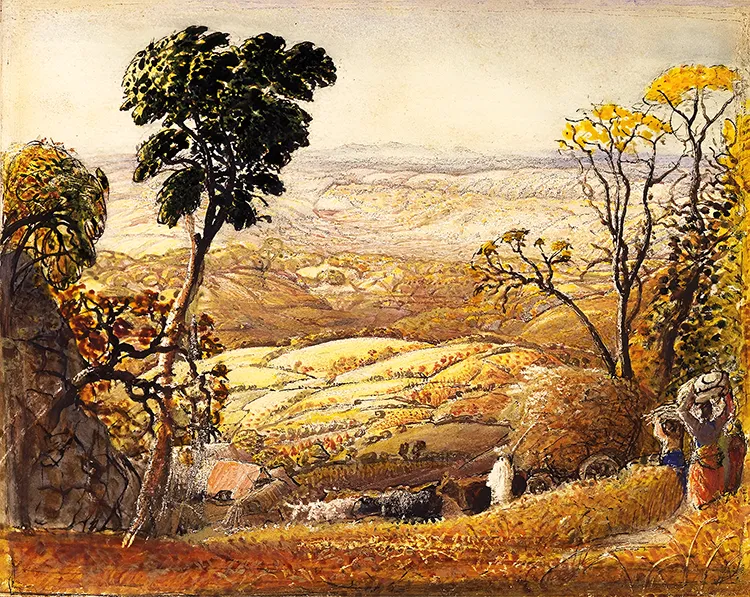

The Darent Valley forms part of the North Downs, a chalk crest that stretches from Farnham in Surrey to the White Cliffs of Dover. Shoreham village is just 30 kilometres from Westminster Bridge – yet this rural idyll could be another world away. To artist Samuel Palmer, it was. Palmer lived in Shoreham from 1827 to 1835 and described the area as ‘an Earthly paradise’. The surrounding hills and woods inspired some of his most famous paintings. Starting at Shoreham railway station, the walk visits Palmer’s elegant former home.

As its name suggests, the Water House overlooks the River Darent. A nearby bench beside the village war memorial provides a picturesque spot for reflection. ‘The Darent is relatively short,’ Alexander says. ‘It springs from the Westerham hills, flows into lakes near Sevenoaks then along this valley. Just beyond Dartford it enters the Thames.’ He continues, ‘Though small, the Darent is very important. The river provides a rare habitat for many plants and animals, including water voles, brown trout and crayfish.’

What makes the river rare is its geology. The Darent is a chalk stream – a waterway fed by a chalk spring that flows over a chalk landscape. There are around 210 chalk streams worldwide, with 160 in southern England. Throughout the walk, the Darent displays their typical qualities: it’s shallow, lined with greenery and startlingly clear. In Shoreham village, Alexander points out scenic brick and flint houses. ‘Flint nodules formed inside the chalk. Using local flint for building is an example of how chalk shapes the valley.’

From the High Street, a path leads uphill into woodland. The steep climb gives a sense of the North Downs’ size. The thick band of chalk was deposited more than 60 million years ago, when most of Britain was covered by warm, shallow seas. Chalk formed gradually from the compressed shells of tiny sea creatures. Tectonic activity later pushed up and folded the soft white rock into a huge, elongated dome. Over millennia, erosion moulded the Downs into undulating slopes.

Shoreham Cross lies on the slope above the village. Like the Uffington Horse or Long Man of Wilmington, it’s an artistic chalk cutting. It was created in 1920 after a suggestion by resident Samuel Cheeseman, whose two sons were killed in the First World War. As the sound of the Spitfire fades, Alexander and I look over the valley. ‘My great-grandfather moved to Shoreham from Scotland in 1892, arriving by train with 17 Ayrshire cows. My family have been farming in the valley ever since.’ Alexander explains the scenery below us: ‘Beside the Darent is floodplain that submerges in winter. Realistically, all you can grow there is grass for cows and sheep. Further back are fields that used to flood millennia ago. They contain deep alluvial soils, full of minerals deposited by the river. They’re ideal for growing fruit and vegetables. Chalk-rich soils along the valley’s sides meanwhile are suitable for arable crops such as cereals. In my grandfather’s day, the steeper areas higher up were cultivated with horses or small tractors. Modern tractors are too large to use there – so those fields are now managed as chalk grassland.’

We descend the valley then follow riverside paths through gently rolling farmland. In late April, the crops are ankle height and difficult to identify. A gap between a row of poplar trees – standing like giant quills – leads into the fields of Alexander’s farm, Castle Farm. Information boards indicate what’s growing nearby. ‘The signs are an effort to engage people with the landscape,’ Alexander says. ‘Similarly, I wanted this walk to explain what you’re really looking at – how the valley is affected by geology and changes in farming.’

Much has changed since Alexander’s ancestors arrived. Castle Farm has mechanised and diversified. We pause beside a forest of posts. ‘Hops are a staple of beer making. They grow like vines along tall poles,’ says Alexander. ‘From the 1800s, Kent’s expanding urban areas increased the demand for beer. The price of hops is volatile though. By the 1990s, it was so low that we stopped growing them for brewing.’ Meanwhile, another crop was on the rise. We reach a field of scrubby brown hedges: nascent lavender.

Enjoying this article? Check out other Discovering Britain’s…

Castle Farm is the UK’s largest lavender farm, growing more than 44 hectares each year. In early July, the fields are a vibrant purple haze with an equally vibrant scent. They’ve become a visitor attraction, bookable for filming and photography. ‘Lavender is native to the Mediterranean, yet the Darent Valley provides ideal growing conditions. The chalky sloping soils are alkaline and free-draining,’ Alexander reveals. Today, lavender oil is extracted for a variety of medicinal, culinary and cosmetic uses. Lavender was introduced to Britain by the Romans, who used it for washing, cooking, repelling insects and treating wounds. Fittingly, the Darent Valley was a Roman enclave.

Beyond Castle Farm, we head towards Lullingstone Roman Villa. We pass barns converted into offices and former farmland used as equestrian grounds. Lullingstone Country Park provides another example of changing land use. Originally a wild forest, it was enclosed to form a hunting estate for Lullingstone Castle. The villa building soon emerges from among the trees. Dated to 100 CE, it’s one of several Roman sites in or near the valley. ‘The Romans settled here as the area was close to London and the Kent coast. The Darent was much wider then and navigable to the Thames.’

Passing under the impressive Eynsford Viaduct, the walk concludes at Eynsford Bridge. While we had the valley summit to ourselves, the riverside lawns here are dotted with blankets. Families and couples relax, children splash their feet in the weirs. ‘It’s a honey-pot site. On a summer weekend it’s like a beach,’ Alexander says. ‘In winter, though, the ford can flood. Calendars have been made showing different stranded vehicles.’ The image recalls Constable’s painting The Haywain. The Darent Valley is a carefully managed working landscape within the Kent Downs National Landscape – yet in this ‘Earthly paradise’, life can also appear to imitate art.

Go to the Discovering Britain website to find more hikes, short walks, or viewing points. Every landscape has a story to tell!