The international conservation agreement CITES is nearly half a century old. Now, with some parties pushing back against its decisions and other critics pointing to its unwieldy volume of paperwork, its future and effectiveness are uncertain

By Roman Goergen

Listen to this story on The Geographical Podcast

They appear like a green mirage in the middle of the dusty brown landscape of the Kalahari Desert in eastern Namibia – typical trophy-hunting camps, very common for this part of the southwest African state. The sizable plot of Gohunting Namibia, not far from the small town of Gobabis, looks like you would expect: an immaculate, generously watered lawn lined with camel thorn trees leads to guest rooms for the international hunting clientele.

This is where the trail ended on a hot summer day in February for investigative journalist John Grobler as he followed a lead he had picked up on some months ago. The story concerned 170 wild African elephants, an attempt to sell them and the role of the international conservation agreement CITES.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), also known as the Washington Convention, entered into force in 1975. It’s meant to ensure the sustainable international trade of the species of animal and plant that are listed in its appendices. The basic logic of the convention is that a stronger threat or endangerment to the survival of a species should lead to stronger restrictions on the trade in their products or entire specimens.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

The strength of the threat is determined with reference to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), especially its Red List of Threatened Species. In addition, the NGO Traffic, an alliance formed by the IUCN and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), pens extensive analyses ahead of every CITES conference, although none of this is binding on the parties.

Species that are subject to the most extensive trade restrictions are listed under CITES Appendix I – at the moment there are more than 1,000, comprising 395 plant and 687 animal species, including 325 species of mammal. For these, explicitly commercial cross-border trade is highly restricted or subject to quota systems. There are exceptions, however, for captive breeding, sales of live animals and non-commercial shipments. ‘In reality, there is hardly a single species for which there is a total trade “ban”. In most cases, it’s just that there are increased barriers or restrictions to trade,’ says Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes, an expert in the international trade of wildlife products at the University of Oxford.

Appendix II, with more than 37,000 species (more than 5,000 animal and 32,000 plant species), requires a ‘non-detriment’ finding, showing that the export plays no part in the endangerment of the species as a whole. But once obtained, Appendix II export permits ensure a vibrant trade in these species.

While Appendix II-listed species only require an export permit, CITES demands an additional import permit from the country of destination for Appendix I species. CITES Management Authority officers issuing such permits are trained and appointed by the governments of their respective countries. Critics see a conflict of interest in this practice, pointing out that in the case of noncompliance by the authorities of a state, these officers are likely to feel more loyal towards their own government than to the word and spirit of the convention.

African elephants represent a particularly tricky case in all of this. Depending on their range state, they may be listed under either Appendix I or II. At the most recent meeting of the CITES parties in 2019, the already confusing regulations for the Appendix II-listed elephant populations of Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa were amended, leaving some range state governments unhappy, to say the least.

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

Selling elephants

Back at the Gohunting Namibia farm, John Grobler marvels at an imposing structure. ‘Somebody is spending big bucks here,’ he says. A boma (a circular animal enclosure widely used in Africa) encircling about 25 hectares of land and featuring six-metre high earthen walls that were pushed up with bulldozers has recently been erected. ‘It looks like there is an electrified fence on top of these walls and a feeding station on the western side where they’re dispensing lucerne [alfalfa].’

The owner of the farm, trophy hunting operator Gerrie Odendaal, doesn’t deny what’s behind those walls – about 20 wild-caught African elephants – but he won’t show the animals to Grobler, who has a reputation for uncovering links between organised crime and the exploitation of Africa’s resources.

Days go by without further response to Grobler’s request to see the animals. The journalist senses a delaying tactic; he suspects Odendall wants to ship the animals out before the public knows what’s happening. On 12 February, Grobler flies a camera-fitted drone over the boma, revealing 22 elephants, ‘scared witless, thronging in a tight herd the whole time’. Some cows must have been pregnant, because Grobler sees two tiny calves. When he stops at the next petrol station, the journalist finds himself surrounded by police. He’s arrested and the drone is confiscated.

This herd is part of a group of elephants that has been making headlines since December 2020. Back then, the Namibian Ministry for Environment and Tourism published a tender in the newspaper New Era, offering 170 yet-to-be-caught wild elephants for sale. ‘Due to drought and increase in elephant numbers, coupled with human–elephant-conflict incidences, a need has been identified to reduce these populations,’ read the ad.

The move drew international attention. In an open letter, 60 well-known animal activists and conservationists, led by the UK-based Born Free group, protested against the measure. The letter questioned the scientific sense of the capture, offered alternatives and warned about negative long-term effects on Namibia’s elephant populations. Moreover, the signatories stated that the move was in contravention of CITES. The 2019 annotation to CITES stipulates that export permits should only be granted where Appendix II elephants are moved to ‘in-situ conservation programmes’ – in-situ meaning that the conservation programme must be within a country belonging to the natural range area of the elephants. Hence, under CITES, the legality of Namibia’s actions hinges on the identity of the buyers.

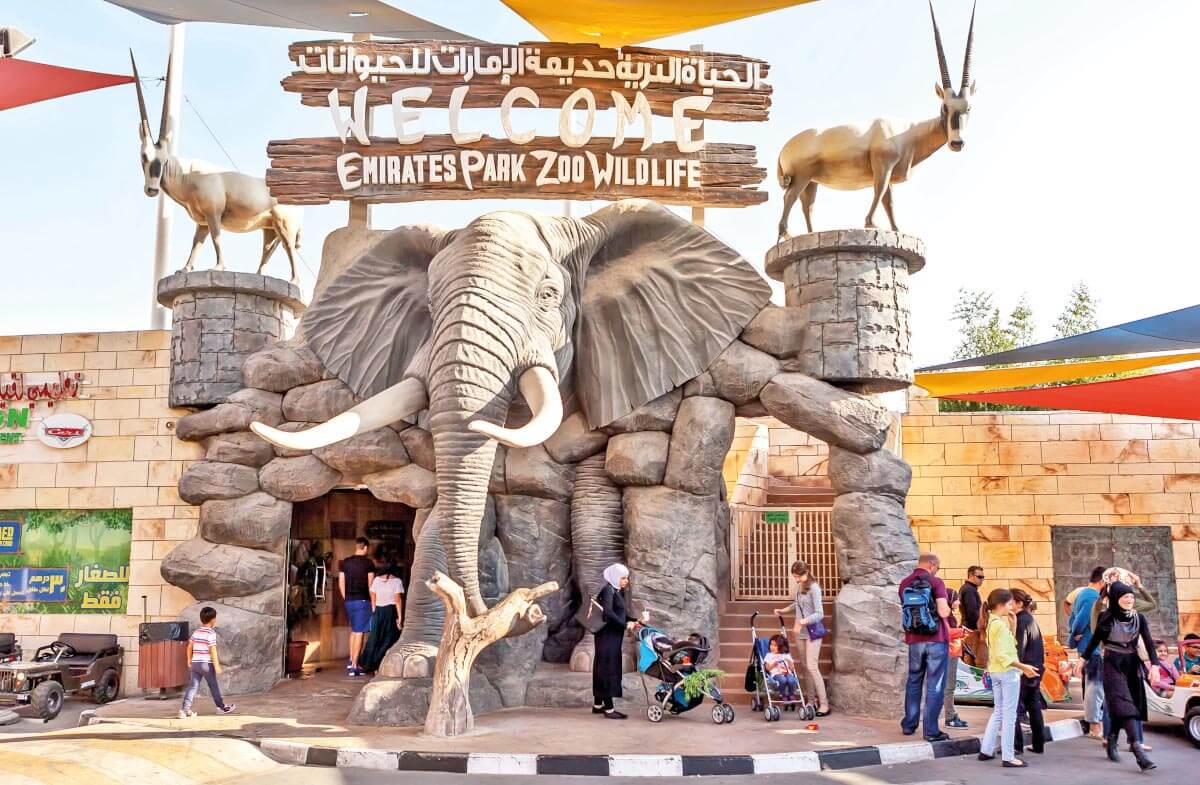

In August 2021, the government announced that it had sold 57 of the 170, stating that 42 of them would be transported abroad, without giving further details. The Namibian media began to speculate about zoos in the United Arab Emirates. Swiss documentary filmmaker Karl Ammann, world famous for his revelations about the Asian tiger bone trade, says that he knows more than just rumours. ‘These elephants will go to Al Ain Zoo (Abu Dhabi) and the new Sharjah Safari Park (Dubai),’ he says, claiming to have seen the relevant paperwork. These two locations are neither in-situ conservation destinations nor range countries of African elephants. At the start of March, the Namibian Government confirmed that the 22 elephants from Odendaal’s farm had arrived in Dubai.

Critics claim that the Namibian government is interpreting the rules for its own uses, assuming that it can choose whether to issue export permits under Appendix I or Appendix II. Under Appendix I regulations, nonAfrican destinations are acceptable as long as the use is for non-commercial purposes – a clause that activists say was originally intended to allow for the non-commercial shipment of ivory carvings, for example, is quietly being applied to live exports. Even though zoos pay hefty sums for the animals, CITES still regards them as educational institutions and hence not commercial. ‘However, it looks like pretty much every player involved is in it for purely commercial reasons,’ says Ammann.

Party politics

The debate over Namibia’s elephants is indicative of a much wider conflict within CITES. Simply put, CITES regulations are being regarded as annoying and bothersome by a growing number of countries.

At the core of the conflict stands a debate about what, precisely, conservation is supposed to accomplish. Is trade in endangered or threatened species categorically bad? Are restrictions or even bans the only working tools to save animals and plants from extinction? The vast majority of strictly defined animal welfare organisations, committed to humane standards, say yes. But the environmental authorities of some countries, along with certain conservation groups that look at a broader, ecosystem-wide picture, think differently.

The CITES Conference of the Parties (CoP) convenes every three years, during which 183 countries, as well as the European Union, vote on proposals. EU members have one vote each, but the bloc votes as one on principle, thus standing for 27 votes and a significant amount of influence. ‘CITES regulates trade in about 38,000 species and within the convention, most decisions about most of them are taken by consensus,’ explains John Scanlon, secretary general of the convention from 2010 to 2018. ‘But there are a number of issues that do become contentious – they have been around the international trade in ivory, rhino horn, hunting trophies and certain marine species.’ Votes about these issues, often hotly contested, require a two-thirds majority to change the status of a species.

An ever-increasing number of ‘observers’ – organisations with a vested interest in what’s being decided – also attend CoPs. The list of such participating groups ranges from the typical animal-welfare NGOs to trophy-hunting associations and ethnic minorities that make a living by hunting or trading in a particular species. Observer delegations are prohibited from voting or even submitting proposals, but they can organise side-events during which they can try to convince delegates to embrace their views. However, uncertainty about how much they’ll be heard at conferences has motivated some observers to adopt a different strategy that sees them convince a party to the convention of a certain campaign in advance and ask their delegation to be champions of that initiative, for instance by filing a formal proposal on behalf of the observer group. This practice is the root of bitter disagreements.

‘This kind of lobbying is a very big problem for us,’ complains Patience Gandiwa, director at the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. Gandiwa claims that Western animal welfare groups in particular take over the votes of ‘smaller and weaker states’. She says that the environmental policies of such countries come to mirror the environmental policies of the NGO. Her complaint is shared by the ministers of environment from the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which has 16 member states representing roughly 300 million people.

This accusation tends to focus both on range states of the animal in question that are small and have weak governance (the Elephant African Coalition, with 32 member states, is a particular target; the media in SADC countries has gone so far as to call them ‘marionettes of the West’) and countries that have no skin in the game because they either have no populations of the disputed animals or carry out no trade in their products. At CoP18 in Geneva in 2019, Gandiwa’s delegation from Zimbabwe, alongside her colleagues from other SADC countries, suffered one defeat after another in the votes, in particular with regard to elephants and rhinos. The parties also voted in favour of the inclusion of giraffes in Appendix II, another point of contention for the SADC. Just like those of elephants, giraffe populations are considered to be relatively healthy in the south of the continent, while there is a grave endangerment to the species in other parts. Zimbabwe asked in vain for a geographical separation of its populations under the rules of CITES, just like for elephants.

The SADC states insist that they should be permitted to trade in a species if they can prove that one or more geographically specific populations have healthy numbers and are therefore deemed to be safe. But Gandiwas claims that scientific studies testifying to exactly that are often ignored by the convention. She insists that decisions shouldn’t be forced into a vote if existing ‘science and facts’ contradict the possibility of endangerment, at least for a specific region. ‘Using voting as the only mechanism to determine an outcome of a decision ignores glaring facts and science,’ says Gandiwa.

SADC politicians are displeased with the wide-ranging rejection within CITES of a conservation philosophy that they claim has led to healthy numbers of wildlife in their countries. Such a philosophy has a pro-trade agenda at its centre and includes often-vilified ideas, such as trophy hunting. They say that a commercial interest in a functioning ecosystem will safeguard conservation, the logic being that wildlife and plants should essentially pay for their own protection by allowing some of them to be captured, killed or harvested in order to foot the bill for their conservation, or by providing an economic incentive to local communities that live side-by-side with wildlife to protect these resources. ‘It’s true that South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and, in parts, also Zimbabwe have managed such sustainable use with trophy hunting relatively well – but not universally well,’ says Colman O’Criodain, policy manager for wildlife practice at WWF. ‘But other SADC states, such as Tanzania, are completely hopeless.’ At CITES CoPs, O’Criodain presents the position of his organisation, which was founded in part by game hunters and isn’t always adverse to the idea of sustainable use of wildlife.

Organisations that regard animal protection and welfare as their priority have a different philosophy. To them, an evolved and humane concept of conservation as a sum of its natural parts must consider the wellbeing and protection of exactly these parts, even down to individuals. These groups emphasise that damaging parts means damaging the whole – and that side effects and long-term effects of killings, captures and other interferences with animal populations or other parts of an ecosystem may only materialise after some time has passed. They question whether concepts of conservation that include consumptive use and trade really aim to preserve a system for the sake of its participants and not just for the sake of profit. Consequently, an ecosystem would only be protected for as long as it’s profitable and not for as long as it’s valuable for reasons beyond profit, for instance for biodiversity or climate protection.

Carnivore conservationist Gail Thomson observes human–wildlife conflicts in Namibia and neighbouring Botswana, and supports government programmes for local communities to run their own conservancies, in which they offer trophy hunting. According to her account, the controversial group of Namibian elephants started to become a problem when they moved, motivated by a severe drought, from neighbouring communal land and national parks onto freehold farmland. ‘Farmers suggested that the ministry of environment should reduce elephant numbers and allow elephant hunting to cover the costs incurred. Others suggested culling them and selling the meat,’ Thomson says. That the government opted instead to capture and translocate them should have been met ‘with interest and support rather than harsh criticism’.

John Grobler suspects that the severity of the conflict has been exaggerated by the government, which he says also tends to inflate the numbers of elephants. Namibia’s claim to host about 22,000 elephants in the north of the country isn’t based on a headcount but on a projection based on steady growth rates that are all but impossible in nature – something that Grobler calls ‘bad mathematics’. ‘In 2020, only one case of human–elephant conflict was officially recorded,’ he writes.

Meanwhile, animal activists refute accusations of undue lobbying at CITES CoPs, as voiced by Namibia and Zimbabwe. Groups such as Born Free and Humane Society International (HSI) claim that they use legitimate, legal and perfectly ethical strategies by collaborating with parties permitted to vote, in order to formally enter proposals aimed at the protection of species. Since only parties to the convention can formally act at the conferences, there’s simply no other way. ‘Attending a CITES CoP is a serious business that is very costly, and no-one goes into it without a plan of what they want to achieve and how to achieve it,’ says Teresea Telecky, vice president of wildlife at HSI. She believes that SADC states have adopted a repetitive and predictable strategy of accusing groups such as HSI of undue manipulation whenever they lose a vote. ‘I have heard complaints from SADC country delegates for 30 years, starting with their complaints about the decision to list the African elephant on CITES Appendix I.’ To appease the SADC, she says, some elephant populations have been down-listed to Appendix II and even ‘socalled one-off ’ exports of ivory from certain SADC countries have been allowed on several occasions. ‘Now that they have seen how the squeaky wheel gets the grease, they have used this tactic every time they don’t get what they want.’

Even though WWF positions itself differently, Colman O’Criodain also sees evidence of a pattern with regard to recent SADC proposals. ‘They seem to be tabling these proposals just for the sake of making a point, rather than offering proof that they are right,’ notes the CITES veteran.

So, why do these unhappy states not simply quit the convention? ‘The SADC countries have made it clear that if they do not get their way with their pro-trade, pro-use agenda, they will quit CITES as a group,’ says Ammann. Others aren’t sure how serious such a threat really is. For many SADC countries, the dilemma is their often vibrant trade in Appendix II species, including plants and export quotas for hunting trophies. If they quit the convention, they may have to limit such trade to deals with players who have also rejected CITES – and there may not be very many of them. ‘What’s left then may be ivory sales to North Korea or the Palestinian Territories,’ says O’Criodian. So far, it appears that despite all the rhetoric after a lost vote, this kind of trouble is regarded by politicians from the south to be the lesser evil as opposed to risking the loss of trade or trophy hunting tourism.

O’Criodain observes that lobbying at the conferences happens on all sides and regards such actions as perfectly normal. And it isn’t only the animal protection groups that successfully use it. He recalls a painful voting defeat when the trophy hunting lobby at CITES applied similar methods to maintain liberal export quotas for trophies and skins of leopards. ‘Leopard protection at CITES is not a success story,’ he says.

And even the parties themselves lobby. John Scanlon recalls highly contested votes about better protection for marine species at CoP16 in Bangkok. ‘There you had complaints coming from observers that powerful states with fishing industries were exerting influence over smaller states,’ he says.

Trade questions

In the midst of all this disagreement, there’s one thing on which many agree. Actors with different views and philosophies admit that the ever-increasing volume of proposals at the CoPs has led to a pushback against solid science, replaced by politics driven by emotion. ‘Politicians listen to the feelings of their voters at home,’ says O’Criodain. ‘With issues such as trophy hunting or the ivory trade, in the Northern Hemisphere, especially in the USA and Europe, the overall popular feeling is against it. And the NGOs there that stand for that sentiment do have influence.’

Meanwhile, Teresa Telecky points to the so-called precautionary principle, which is often debated at CITES conferences. It more or less stipulates that if there is a clearly endangered species without sufficient scientific data explaining what’s causing the endangerment, said species should be included or uplisted anyway, ‘out of caution’. Not everyone agrees. Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes is convinced that appendix-uplisting doesn’t always yield the intended results. ‘What if trade is actually benefiting the species? What if prohibiting trade unleashes some unfortunate economic effects endangering the species?’ Trade restrictions are notorious for creating unexpected results as they are subject to often complicated economic mechanisms. And whenever there’s a black market, a product will find its way there. Even though most experts agree that increased trade regulations for ivory in 1990 helped elephant numbers to stabilise, similar measures for rhino horn in 1977 didn’t have the same effect.

But what remains in terms of scientific proof is a vicious cycle: no data can lead to no uplisting, and no uplisting can lead to no data. When giraffes were included in Appendix II in 2019, supporters of the proposal argued that the export permit paperwork required from now on will generate data, giving an insight into the trade in the products of the animal. The lack of precisely such scientific data was previously the most prominent argument against the inclusion of giraffes in Appendix II.

However, there’s no doubt that the convention has started to buckle under the weight of its paperwork, paired with a lack of financial enthusiasm among some parties. ‘The agenda of these CoPs has lengthened by about 70 per cent since I started attending these meetings and there is simply much less time for discussions,’ says O’Criodain. More and more proposals are being submitted to change the status of species. Afterwards, the conferences call for scientific studies to investigate the situation, but the secretariat often fails to find a financial sponsor to get them underway, a situation that is getting steadily worse, according to O’Criodain.

Karl Ammann has more drastic words. ‘The CITES secretariat no longer stands up to any of the parties on any of the non-compliance issues – certainly not to players such as China or the Emirates,’ he says. ‘Instead, they rather endorse the exploitation of every loophole anybody can think of.’

‘CITES is now almost 50 years old. It’s a trade-related convention, but it has a conservation objective. The convention itself is agnostic to trade – it doesn’t say trade is good or bad,’ explains Scanlon. But over the years, and in the absence of other instruments, ‘we turned to CITES to do other things’ – for instance to address crime.

‘It is clear by now that we have exhausted the mandate of CITES,’ adds the former secretary, who now heads the End Wildlife Crime initiative. He believes that other conventions and initiatives need to help CITES by reducing its workload and responsibilities. As an example, he says that actual wildlife crime, such as poaching or smuggling, should be addressed by an international crime convention rather than a trade convention and points to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. ‘This convention has three protocols so far – for human trafficking, the smuggling of migrants and the illegal manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms. Wildlife crime could be added under a fourth protocol.’

There is a growing insecurity as to whether CITES is ready for new challenges or even whether it can fulfil the tasks given to the convention. ‘CITES has become part of the problem,’ laments Ammann. With less dedicated or even corrupt states being solely responsible for issuing export permits, he sees no ethical value in anything that carries the seal of the convention. Even WWF official O’Criodain, with his more reserved opinions, identifies a clear problem in the lack of financial support and authority of the convention’s secretariat. ‘You have to deal with countries that are not complying and find out why they are not complying,’ he says. But for that to happen, the secretariat would require funding that currently doesn’t exist, in order to have the power to send investigators to such countries, he points out.

Once again, at CoP19 in November in Panama City, there will be a flood of new proposals, there will be fights and votes with their usual winners and losers, followed by the subsequent search for legal loopholes. It appears that the ageing convention desperately needs support.