In January 2020, numerous African countries suffered internet outages after submarine telecommunications cables in the Atlantic Ocean were cut. The cause of the damage was a massive underwater landslide, the largest ever recorded

By

Beneath the oceans, the continental shelf is etched with underwater canyons that very often dwarf the land-based versions. Sediment flows from the land, down the canyons and eventually settles on the floor of the deep sea. Storms, earthquakes and river floods can trigger rapid flows of water and sediment, known as turbidity currents, that are strong enough to bury, displace or destroy deep-sea infrastructure.

The Congo Canyon is one of the largest in the world. It begins inland, part way up the Congo River estuary, and stretches about 280 kilometres out to sea. Sediment from the landslide that cut the internet cables off Africa’s west coast travelled more than 1,130 kilometres from the river’s mouth and reached a top speed of about eight metres per second.

Mike Clare, a marine scientist at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, researches turbidity currents and landslides. He explains that until very recently, ‘there were no direct measurements of how the processes work within submarine canyons.’ It’s a challenging environment that often requires costly vessels and equipment to explore. ‘The poor sensors that we put in to measure the current were just blasted with sand and mud over several days.’

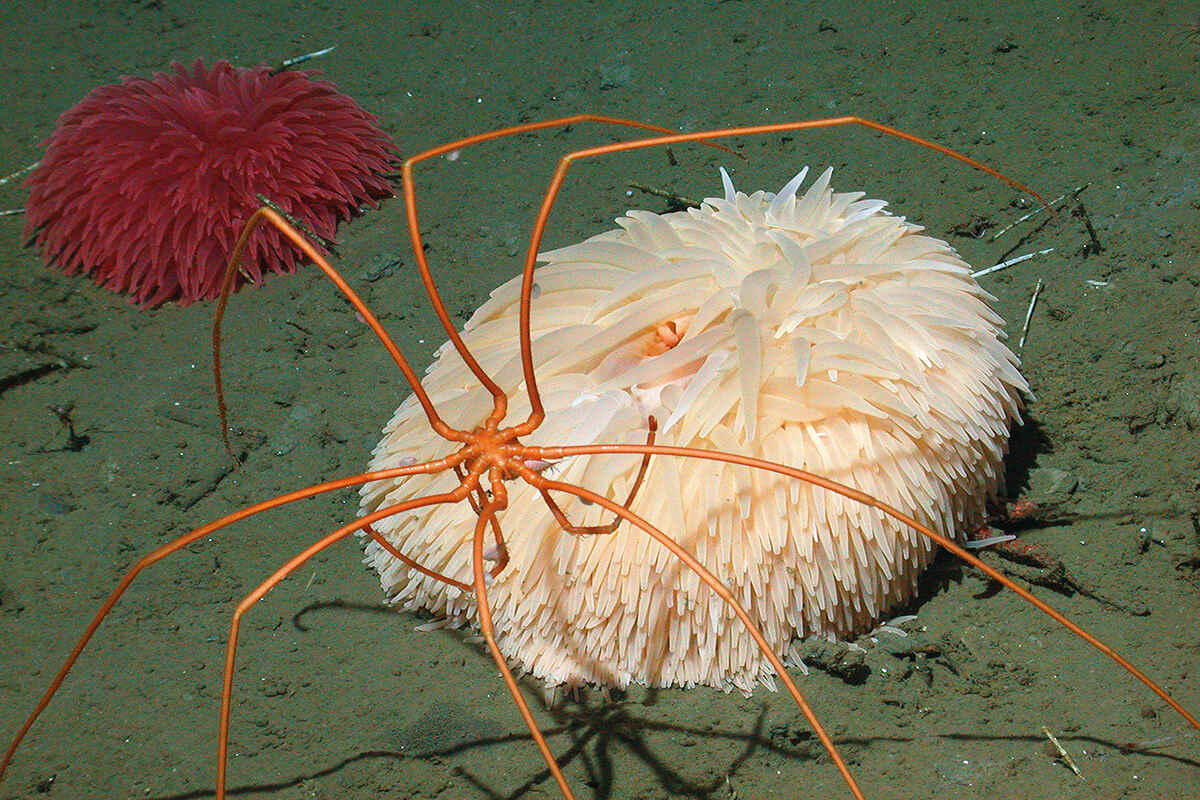

In 2022, Clare and his colleagues published a paper that revealed that a landslide had dammed the Congo Canyon, blocking megatonnes of organic carbon from being transported to the deep sea, where it sustains unique ecosystems that are home to species such as the sea pig, which has long, tube-like feet that stop it from sinking into the mud, and the pom pom anemone.

What this means for those ecosystems is uncertain. ‘Landslide dams have been reported from rivers, but never observed in this way in a deep-sea canyon,’ says Clare. ‘For context, the sediment trapped by the underwater dam was nearly four times as much as the annual sediment flux that comes out of the Congo River.’

Very few submarine canyons have been surveyed from top to bottom. ‘There are maybe only four places where we’ve been to even part of them more than once to get some idea of how the seafloor changes,’ says Clare. One of those places is the Monterey Canyon on the US west coast. Here, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute has developed a device called the benthic event detector – dubbed the ‘smart boulder’ – a motion-sensing instrument that captures data as it makes its way across the sea floor.

So far, however, Clare says that we’re only scratching the surface when it comes to understanding submarine canyons. ‘We still only have maybe a handful of measurements, so it’s a real frontier in scientific exploration.’

OceanIQ, specialists in subsea-cable data and route engineering, estimates that there are currently 2.8 million kilometres of subsea cable worldwide, and there’s plenty more subsea infrastructure in the pipeline. ‘Sometimes, canyons are so long that you can’t route around them – you need to cross them,’ says Clare. ‘The Congo Canyon is a really good example. So it’s vital to understand the potential hazards that they pose to important infrastructure.’