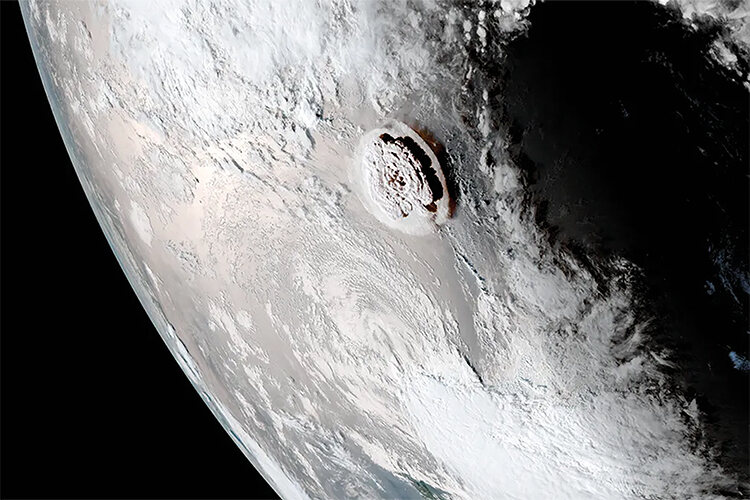

Two massive explosions of the submerged Hunga volcano in the remote Kingdom of Tonga sent a series of tsunamis across the Indian and Pacific oceans, destroyed vast swathes of the surrounding seabed and severed key communications cables that linked the kingdom’s islands to the outside world

Report by Isobel Yeo, and Michael Clare of the UK’s National Oceanography Centre

The primary record of the most explosive volcanic eruption this century was, for several days, to be found on social media. In one video, people stood on a tropical beach filming a band of cloud expanding above them when suddenly a shockwave hit them from the ocean. A sound like a gunshot echoed across the beach and the pressure wave kicked up spray and sand, almost knocking people off their feet. Somebody stood on a church pew in another, filming several feet of water flooding into the building. Videos such as these, quickly uploaded to social media, were to provide the main source of information about what occurred on the evening of 15 January 2022 in the Kingdom of Tonga. Just over an hour later, at a time critical for disaster response, the entire nation was disconnected from the internet.

HUNGA VOLCANO

The Tongan people are no strangers to volcanoes, but they’re more familiar with the relatively small eruptions that occur every few years from the many fully or partially submerged volcanoes that surround the islands of Tonga, on the Pacific Ring of Fire. While they can be hazardous if you get too close, most of these eruptions normally don’t endanger the populated islands that lie tens of kilometres away.

The eruption of the almost entirely submerged Hunga volcano started on 20 December 2021 in a very similar manner. A number of small explosions occurred over several weeks, causing only light ash to fall on the islands that lay downwind. There were few clues during the early phases that this eruption was going to be anything out of the ordinary, and most Tongans, while alert to the eruption, didn’t expect much of an impact on their daily lives from this remote island volcano.

On 14 January 2022, a boat from the Tonga Geological Services, the Tongan government department for geology, sailed close to the volcano and reported increased activity from the vent. The team saw larger explosions than in the preceding weeks and clouds of hot rock and ash, known as pyroclastic density currents, running several hundred metres across the ocean, but there were no obvious warning signs of the immense eruption that was to come. The next day, the volcano catastrophically erupted. The January 2022 eruption of Hunga was the most explosive eruption since the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, which created effects that were felt around the world.

VOLCANOES AND HAZARDS

It’s impossible to say exactly how many of the Earth’s volcanoes lie underwater because scientists haven’t yet completely mapped the ocean floor, but it’s likely that at least two-thirds of the world’s volcanoes are underwater in some capacity.

These volcanoes, some of which are extremely remote, play an essential role in maintaining life on Earth. They also pose a wide range of hazards to communities and the environment. Very deep water can exert enough pressure to suppress volcanic explosivity, but in shallower waters, the interaction of volcanic material and water can generate additional hazards to those posed by volcanoes on land.

Volcanic hazards on land are better understood than those underwater. Most people have seen videos of lava flowing across streets or ash falling on roofs. However, the addition of water can increase the risks posed by volcanoes, as well as introducing other dangers, such as tsunamis, steam-driven explosions, the eruption of floating volcanic rock, which can affect shipping, and underwater flows of volcanic material.

Tsunamis pose a serious risk to life because they can travel across the ocean and those induced by volcanic activity often don’t produce the kinds of signals that can be detected easily on tsunami warning systems. The resulting waves can completely inundate coastal communities, as was tragically demonstrated by the 1883 Indonesian tsunami, generated by the collapse of Krakatau volcano, which killed more than 26,000 people.

Very few underwater volcanoes are monitored, which partly explains why events such as the 2022 Hunga volcano eruption come as such a surprise. As a result, scientists currently don’t have the means to detect when most underwater volcanoes are approaching a major eruption. On land, volcanoes that sit near population centres are normally monitored by specialised instruments designed to detect signs of unusual activity or unrest that may indicate an eruption is coming, and satellite surveys can reveal changes in the shape of a volcano due to rising magma. While it’s impossible to know for certain if or when a volcano will erupt using these measurements, events such as the Icelandic Litli-Hrútur eruption in July 2023 have shown how they can be used to forecast volcanic activity with surprising accuracy.

We aren’t currently prepared to monitor the limited number of underwater volcanoes we’ve identified, as equipment is expensive and many of these volcanoes lie in economically deprived countries and territories. Without monitoring, the only information available on volcanic activity underwater is from the global network of seismometers and hydrophones, which will detect large earthquakes and some explosive eruptions but rarely capture the much smaller events that may be key to forecasting future activity.

A NOISY NEIGHBOUR

At least 30 volcanoes have been mapped within waters around Tonga, only a few of which extend above the sea surface. None of these volcanoes are presently monitored, exposing a blind spot in our awareness of the potential hazards they may pose in the future. The Hunga volcano lies around 60 kilometres northwest of the island of Tongatapu, at the northern end of this chain of volcanoes.

Hunga volcano has been a noisy neighbour. Notable eruptions occurred in 1998, 2009 and 2014, although these were relatively small and didn’t endanger Tongan islands. The 15 January 2022 eruption was very different.

Two major explosions occurred ten minutes apart, generating numerous tsunamis. Maximum reported wave heights were 15–20 metres, causing substantial damage to the regions they impacted, primarily the westward-facing coastline of the islands of Tongatapu and ‘Eua, and the Ha’apai island group.

The damage to many buildings was substantial, particularly in the islands of ‘Eua, where more than 100 buildings were damaged, and Mango, which was made uninhabitable. Four people in Tonga died as a direct impact of the eruption, all of them swept out to sea by waves. Although tragic, this number was remarkably small, considering the scale and size of the waves. This was primarily because people had been educated in the signs of approaching tsunamis and because the waves arrived during daytime.

Shorelines of other nations were also affected by the tsunamis. Two people drowned and coastal flooding occurred as far afield as Peru on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. There was also damage to vessels in southern Japan, while villages and infrastructure on Fijian islands, New Zealand, American Samoa and Vanuatu also reported damage.

Understanding the catastrophic impacts of the eruption on Tongan communities was about to become far more challenging. Around 99 per cent of internet traffic is transmitted through underwater cables laid on the ocean floor. Tonga is served by two cables: a domestic cable that connects the island groups and an international cable that connects Tongatapu to Fiji, and on to the rest of the world.

Both of these cables were severed shortly after the eruption, effectively cutting off all communication between Tongan islands and with the rest of the world. The island of Mango, at the time home to a community of around 30 people, triggered an emergency beacon. However, with no way of contacting the islanders nor reaching the remote island for several days, it was unclear what the extent of the damage was. With the communications down, there was no way for islanders to know if the signal they were sending was being received.

UNDERWATER IMPACTS

Scientists from multiple institutions around the world responded quickly to the eruption, and the first research expedition to the area occurred just a few months later, led by New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmosphere, quickly followed by a second expedition by Shane Cronin from the University of Auckland.

Their findings were astonishing. They revealed that underwater flows of volcanic material travelled more than 100 kilometres from the volcano at speeds faster than any underwater flow that has been measured before. The impact on everything in their path was devastating. Much of the seafloor on and around the volcano was covered in volcanic deposits, and all of the life around these areas appeared to have been completely wiped out. But there’s hope for recovery as biologists have identified what appear to be safe spots, sheltered from the submarine flows.

For the subsea cables, the event was catastrophic. Cables were buried up to 22 metres deep by volcanic material, along a distance of up to 105 kilometres. The remarkable extent of cable damage, combined with the remoteness of the nation of Tonga itself, meant that repairs were extremely challenging. Collaboration among cable companies, which combined resources, ensured the international cable was repaired within five weeks. However, repairs to the domestic cable had to wait 18 months due to the length of new cable that had to be manufactured.

FUTURE RISKS

While thankfully eruptions on the scale of Hunga volcano are rare, submarine eruptions aren’t. Both eruptions and steep volcanic slopes can generate landslides and tsunamis, posing a serious risk to coastal communities. Two major changes are required to reduce these risks. One is better mapping of the seafloor. An international effort named Seabed2030 is currently underway to help identify active volcanic centres, allowing scientists to understand better which areas might be at greatest risk.

The other is a need for monitoring of submerged volcanoes, which is more challenging. However, the global scientific community and governments have a responsibility to coordinate and cooperate to fill this gap. There are many monitoring solutions in development across the world, some of which aim to use the same cables that could be at risk from volcanism to detect shallow seismic activity associated with rising magma. However, we’re a long way off large-scale implementation of these technologies globally. For now, we remain almost entirely in the dark about when, where and just how big the next volcanic eruption in the oceans will be.

The authors wish to thank Professor Shane Cronin (University of Auckland), Marta Ribo (Auckland University of Technology), Sarah Seabrook, Sally Watson, Richard Wysoczanski, Kevin McKay and Professor Mike Williams (National Institute for Water and Atmosphere), Rebecca Carey (University of Tasmania), and Taaniela Kula (Tonga Geological Services) for their expertise and advice while writing this article