The Yellowstone Caldera, the supervolcano in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming formed 640,000 years ago in a massive explosion. Will it happen again?

By

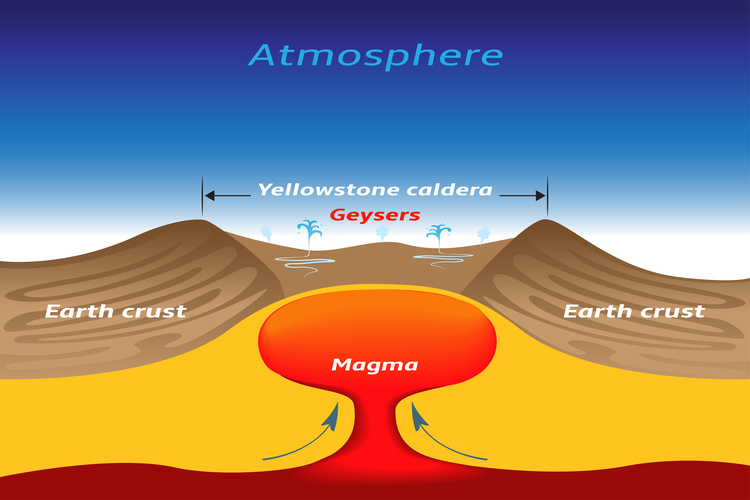

The Yellowstone Caldera, also known as the Yellowstone Supervolcano, is an enormous volcanic depression measuring approximately 50 kilometres by 70 kilometres (30 miles by 45 miles), located in the western-central area of Yellowstone National Park in northwestern Wyoming. The word ‘caldera’ originates from the Spanish word for ‘cauldron’ – and this deep crater covers a large proportion of the Yellowstone National Park. The Yellowstone Caldera is over 640,000 years old, and is the youngest of the three largest calderas in the park.

Formation of Yellowstone Caldera

Around 66 millions ago in the Cenozoic era, extensive volcanic activity, glaciation, and widespread mountain forming shaped the region. This included the formation of the Abasaroka Range along the current park’s north and east sides.

Related articles

Around 16.5 million years ago, a period of intense volcanism began near the borders of present-day Nevada, Oregon and Idaho, causing widespread volcanic eruptions. As the North American plate moved southwest over a shallow body of magma, a 500-mile trail of more than 100 calderas was created. Usually, calderas are formed after the collapse of the top of a volcanic cone, or group of cones, due to the partial emptying of magma chambers during large eruptions.

Subsequently, there have been three more major eruptions in the Yellowstone area, two of which expelled more than 240 cubic miles of magma – a magnitude of 8, the highest ranking on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.

The earliest major eruption, The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, occurred around 2.1 million years ago, and the Mesa Falls eruption approximately 800,000 years ago. The Lava Creek eruption led to the formation of the Yellowstone Caldera, 640,000 years ago.

These eruptions caused huge quantities of hot volcanic rocks to spread outwards. Hot ash, pumice and other rock fragments accumulated and stuck together to form thick sheets of hard rock. Volcanic debris from these eruptions covered most of the continental USA, with some material found as far away as Louisiana.

Magma may lie just 3 to 8 miles beneath two resurgent domes inside the Yellowstone Caldera today, the Sour Creek Dome and the Mallard Lake Dome. Both domes are able to inflate and subside as magma volume and hydrothermal fluids shift between them. Over the past century, the caldera floor has tilted to the south due to net inflation, causing trees in Yellowstone Lake’s southern shores to stand in water, and a sandy beach to form at the north end of the lake.

The last volcanic activity at Yellowstone was approximately 70,000 years ago, when rhyolitic lava flows erupted. As a result of the largest flows, the Pitchstone Plateau in southwestern Yellowstone National Park was formed.

An unlikely eruption

According to the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, the most likely activities that will occur at Yellowstone include hydrothermal explosions (steam and hot water eruptions), large and moderate earthquakes or lava flows. Since the hydrothermal explosion at Black Diamond Pool in Biscuit Basin in July 2024 – which caused the basin to close for visitors for several days due to damage to a boardwalk – several smaller water eruptions have been reported.

Hydrothermal explosions or lava flows are not as devastating as the eruptions which cause calderas, with lava slowly oozing from the ground over a prolonged period.

‘The Earth will see super-eruptions in the future, but will they come in Yellowstone? That’s not a sure thing,’ said Scientist-in-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in California, Jacob Lowenstern. ‘Yellowstone’s already lived a good long life. It may not even see a fourth eruption.’

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) report that Yellowstone is behaving as it has done for the past 140 years.

‘Odds are very high that Yellowstone will be eruption-free for the coming centuries,’ the USGS said.

The Yellowstone volcano could also die out. The magma chamber below Yellowstone is under two competing forces, the heat from below and the relative cold of the surface. If the heat from underneath decreases, the chamber could freeze and turn into a solid granite body.

According to a 2022 study in Science journal, one of the magma reservoirs underneath the Yellowstone Caldera holds more magma than previously estimated – but still does not meet the required threshold to cause a massive eruption.

Previously, scientists believed that the reservoir was mostly solid – containing just five to 15 per cent of melted rock – but they concluded that this figure is instead 16 to 20 per cent. The more volume of melted rock, the higher the likelihood of the volcano erupting. The Earth hasn’t created more magma; rather, the scientists reanalysed existing seismic data to generate their findings.

This new figure is still much below the threshold of 35 to 50 per cent liquid magma – which scientists currently believe is the level required to trigger an eruption.

But if a caldera-forming Yellowstone eruption were to occur, the USGS believe it would likely alter global weather patterns and significantly impact human activity, particularly agricultural production, for ten to 20 years. For example, global temperatures were temporarily altered by the relatively small eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Phillippines in 1991. As of yet, scientists are unable to specifically predict the consequences and duration of such a large-scale eruption.

Earthquakes in Yellowstone

The Yellowstone region is extremely seismically active, experiencing around 1,500-2,500 located earthquakes each year. While most of these earthquakes are such low magnitude that humans cannot feel them, they are detected by seismological monitoring equipment.

The 7.3-magnitude Hebgen Lake earthquake in 1959 killed 28 people, and triggered a major landslide in Madison Canyon and rockfalls in Yellowstone that blocked roadways and caused major damage to structures in West Yellowstone.

More than 48,000 earthquakes have been recorded in the Yellowstone region since 1973 – but over 99 per cent were magnitude 2 or lower, and are not felt by anyone. One magnitude 6.0 earthquake was recorded in 1975, two earthquakes in the magnitude 5 range, 29 earthquakes in the magnitude 4 range, and 379 in the magnitude 3 range.

Earthquake swarms – earthquakes that cluster in time and space – are responsible for around 50 per cent of the seismic activity in Yellowstone. While most swarms are small and contain 10-20 earthquakes, lasting only for a few days, others can contain thousands of earthquakes and last for months.

In June 2023, the University of Utah Seismograph Stations reported 78 earthquakes in the Yellowstone National Park region – the largest a minor 2.8 magnitude earthquake located about 17 miles north-northeast of Moran, Wyoming, on 17 June at 11:58 am. In August 2024, around 40 located earthquakes were reported in the Yellowstone Caldera, with a maximum magnitude of 2.0. These quakes follow the normal background levels expected from the site.