A new method for pinpointing the precise location of magma chambers could help scientists forecast volcanic eruptions

By

On 19 September 2021, six new vents in a volcanic ridge on the island of La Palma in Spain’s Canary Islands erupted. For 85 days, the Cumbre Vieja ejected ash into the air and streamed with rivers of molten rock, destroying more than 1,000 homes and smothering roads and banana plantations. More than a year later, many residents are still housed in temporary accommodation and ash still covers the island.

During the eruption, volcanic dust piled up in the plaza of Las Manchas, a town to the north of Cumbre Vieja, where it was scooped up by Esteban Gazel and Kyle Dayton, two visiting researchers from Cornell University. Like many scientists, they were eager to learn from this open-air laboratory, which offered a rare opportunity to study an ongoing eruption first-hand. The samples of tephra – a term that encompasses all fragments of rock thrown from a volcano, including ash – would help them see deep into the volcano’s underground plumbing system and gain a better understanding of where the magma was coming from. ‘Where is magma stored before an eruption?’ asks Gazel ‘That is the big question.’

Many of the features of an eruption – such as its duration, the style of eruption (explosive or a slower flow of lava) and the likelihood of its occurrence – relate to the depth of magma storage. Magma chambers can be active for thousands of years, yet their exact locations within the Earth’s crust are often poorly known. Even the magma depth of active, well-researched volcanoes can be difficult to pinpoint; estimates for the chamber beneath Hekla, one of Iceland’s most active volcanoes, range from 5–6 kilometres to more than 20 kilometres.

In recent years, satellite imagery has proven useful in finding magma chambers, revealing ground deformations where the earth has risen above stored magma, but this technique is of limited use when it comes to determining the magma’s depth. Looking at the chemical composition and appearance of expelled lava can, however, provide some clues.

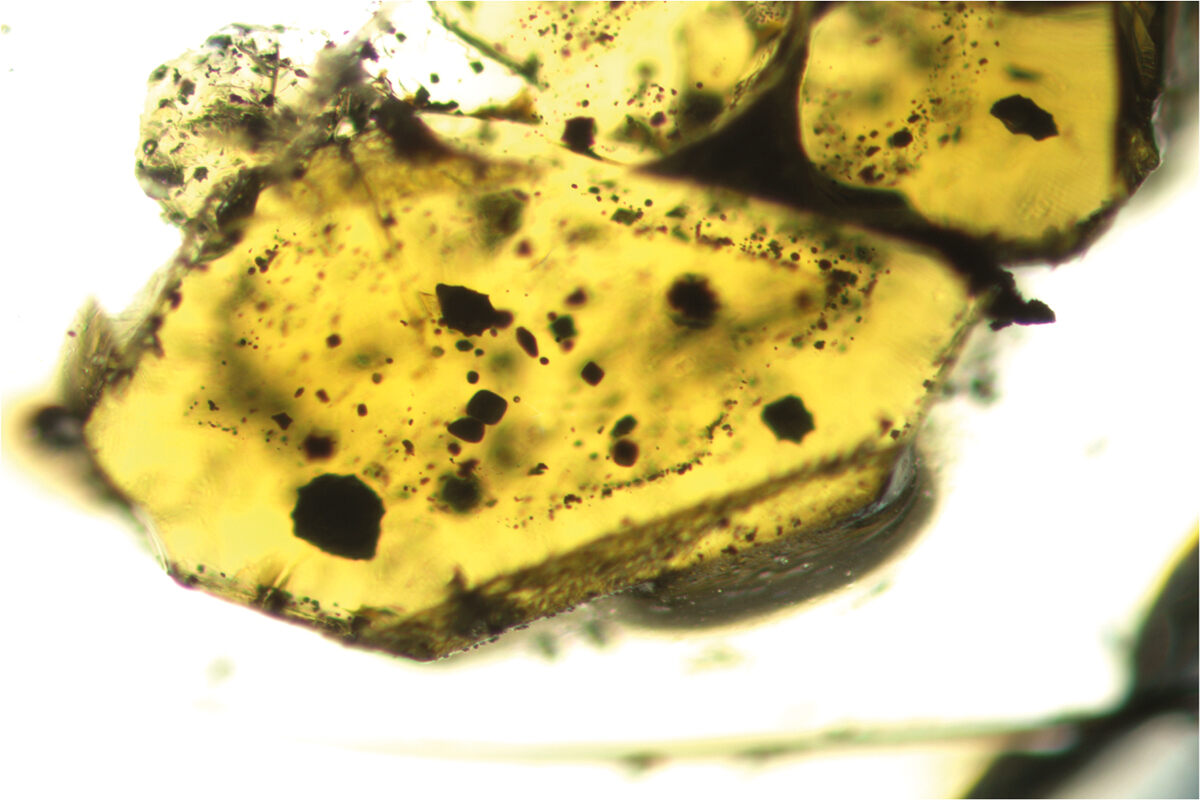

One of the most common ways of doing this involves cooling and heating tiny bubbles of fluid trapped inside mineral crystals, called ‘fluid inclusions’, to record different conditions at different depths below the Earth’s surface. It’s a technique often used in mineral exploration to identify deposits of critical minerals, oil and gas. Under a microscope, scientists can see the different transformations of the inclusions, from solid to liquid to gas. When the experiment reproduces the original state of the sample, the conditions are likely to be the same as those in the magma chamber. It’s a time-consuming method that requires a trained eye and can take weeks to yield results.

Instead, Gazel and his colleagues used a technique called Raman spectroscopy to measure the density of carbon dioxide in the fluid bubbles under different conditions. Raman spectroscopy can measure much smaller fluid inclusions, down from tens of microns to just one (one micron is equivalent to one one-thousandth of a millimetre). ‘It opens up a world of tiny inclusions, usually less than ten microns, that are commonly found in volcanic systems,’ says Gazel. ‘The other advantage is that it takes the human factor out of the equation. We don’t need to see the different phase transformations anymore.’

Tiny inclusions trapped inside cooled lava reveal the depth of the magma chamber. Image: Gazel Laboratory

Gazel says that the real breakthrough, however, is how quickly these measurements can be made. From the four samples taken from La Palma, 140 inclusions were prepared and measured, resulting in a magma chamber pressure (and therefore depth) reading in less than a week. ‘Don’t get me wrong,’ he adds, ‘it took me three whole years to set up the method and calibrate all the apparatus.’ He credits a sudden abundance of time during the pandemic for allowing him to concentrate on the problem at this level of detail. But with the hard work now done, Gazel says that anyone with a Raman spectrometer can replicate the experiment. ‘The idea is that every agency should be able to do this; it’s our goal that this becomes a universal method to study volcanoes.’

It’s thought that around 1,500 volcanoes are potentially active worldwide, and at least one billion people live close to them. Every year, an average of 50 eruptions occur. Gazel says that more precise data on magma locations is needed to forecast and prepare for eruptions, both of which are essential to saving lives. ‘Understanding volcanoes is not as hard as understanding earthquakes,’ he adds. ‘We just don’t have the data.’ He points to Cumbre Vieja, where international and interdisciplinary collaboration was facilitated by the Spanish government, as an example of how more discoveries can be made. ‘La Palma is an excellent example of how to manage an eruption and also do science at the same time, at the highest level. There is going to be a lot of good data coming out of it all.’