Tim Marshall argues that world maps should centre the Indo-Pacific – the world’s new economic and political hub

Geopolitical Hotspots

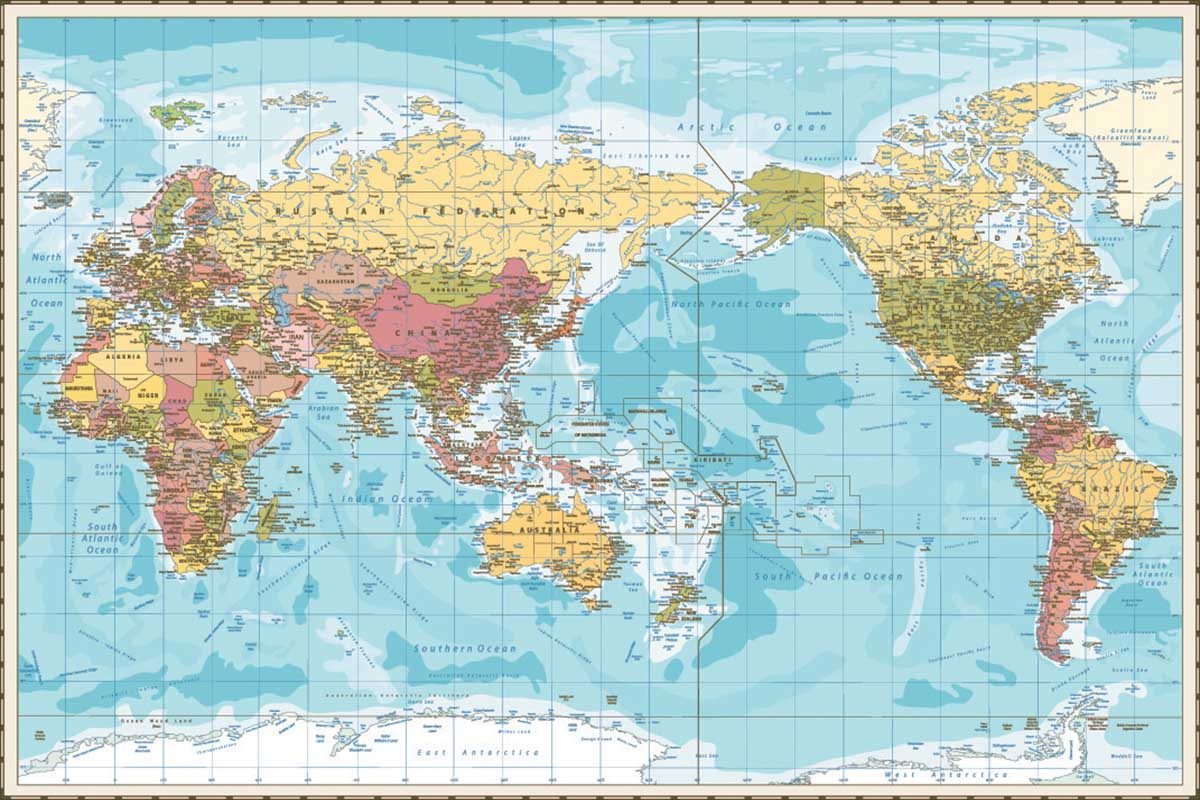

Look at a flat map of the world. It probably has Europe slap-bang in the centre. If so, it’s out of date. It should be the Indo-Pacific region.

As a learned reader of Geographical, you know there’s no centre on the outside of a planet, but the design of the classic Mercator map of our world puts Europe in the middle and reflects the views of those who first circumnavigated it. It also perpetuates the subconscious idea of a dominant Europe, even though the economic and political centre of the world has shifted.

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

The Indo-Pacific is an idea whose time has come. It has supplanted the term ‘Asia-Pacific’ because the world has moved on. In the 21st-century globalised world, the economic engine is the centre, and that centre is the Indo-Pacific. Definitions of its scope vary. A catchy one is ‘From Hollywood to Bollywood’, but that’s a narrow view. A wider one encompasses Africa’s east coast to the USA’s west coast. Among the strategically important points in between is the mouth of the Red Sea (leading to the Suez Canal), the Strait of Hormuz, the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea, the Luzon Strait (between Taiwan and the Philippines) the Pacific Islands, and Hawaii. Also between them is the continent of Australia – the hinge country of the Indo-Pacific.

The Malacca Strait alone carries about a third of the world’s traded goods, including about 80 per cent of the oil heading for northeast Asia. Japan relies on this route for its energy supplies and Australia relies on Japan to refine crude oil and ship it on down to them. Small wonder the two have increasingly close military ties.

Conflict in the region could disrupt trade in a manner not seen since the Second World War. There are numerous flashpoints between China and a range of countries, including Japan, the Philippines, India, Taiwan and the USA. Australia is looking nervously to its north as China attempts to move past the First Island Chain. Beijing is already investing in ports in places such as Papua New Guinea and recently signed an agreement with the Solomon Islands allowing visiting rights for its navy. It’s also continuing to develop the artificial islands it has built in disputed waters in the South China Sea.

You may also like

The term Indo-Pacific can be traced to Karl Haushofer, a German geopolitical writer of the 1920s, but its modern use was launched in 2007 by the then prime minister of Japan, Abe Shinzo. He delivered a landmark speech to the Indian parliament titled ‘The Confluence of the Two Seas’. It was a clever move. ‘The Confluence’ was a reference to a treatise from 1655 written by a Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh, in praise of the similarities of Hinduism and Islam. Abe said: ‘We are now at a point at which the Confluence of the Two Seas is coming into being. The Pacific and the Indian oceans are now bringing about a dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and of prosperity.’ He was trying to draw India into the new reality that like-minded countries needed to come together to contain Chinese dominance of the region.

Several countries, including Australia, adopted the phrase Indo-Pacific and the concept is now widely accepted, although some geopolitical thinkers remain unconvinced. Japan also pioneered the phrase ‘Free and open Indo-Pacific’, which was then picked up by the USA and incorporated into its National Security Strategy in 2017.

The loose naval agreement known as ‘The Quad’ (Japan, Australia, the USA and India) is related to this thinking, as is the AUKUS submarine deal between Australia, the UK and the USA. Other European countries, including the Netherlands and France, buy into a free and open Indo-Pacific, and have sent naval vessels on exercises to underline the point. There are already tensions over China’s island-building activities. Beijing claims its artificial islands are as much part of China as is Sichuan. Given that it also then lays claim to sovereign waters and exclusive economic zones in international sea lanes, a forthright ‘exchange of views’ seems to be inevitable.

Nevertheless, China hasn’t bridled at the phrase ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. After all, it needs free trade to continue its success story, but it also knows that behind the idea of the Indian and Pacific oceans as one super-region is nervousness about Beijing’s potential to control it. How all of these powers manage this rivalry at sea will be among the defining relationships of the century.

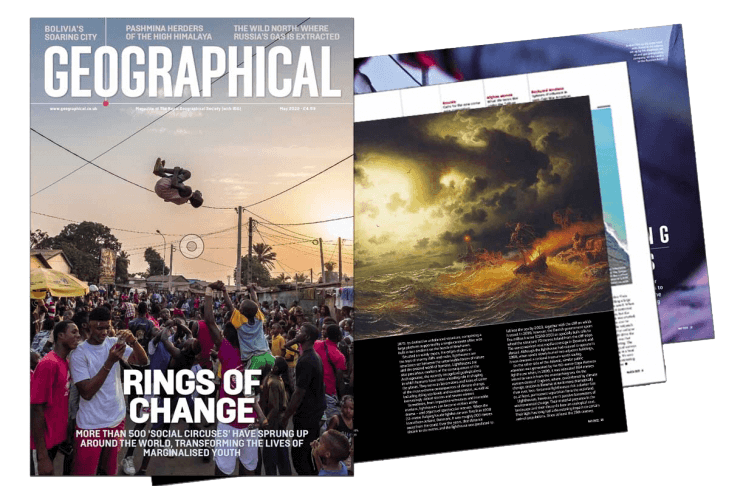

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!