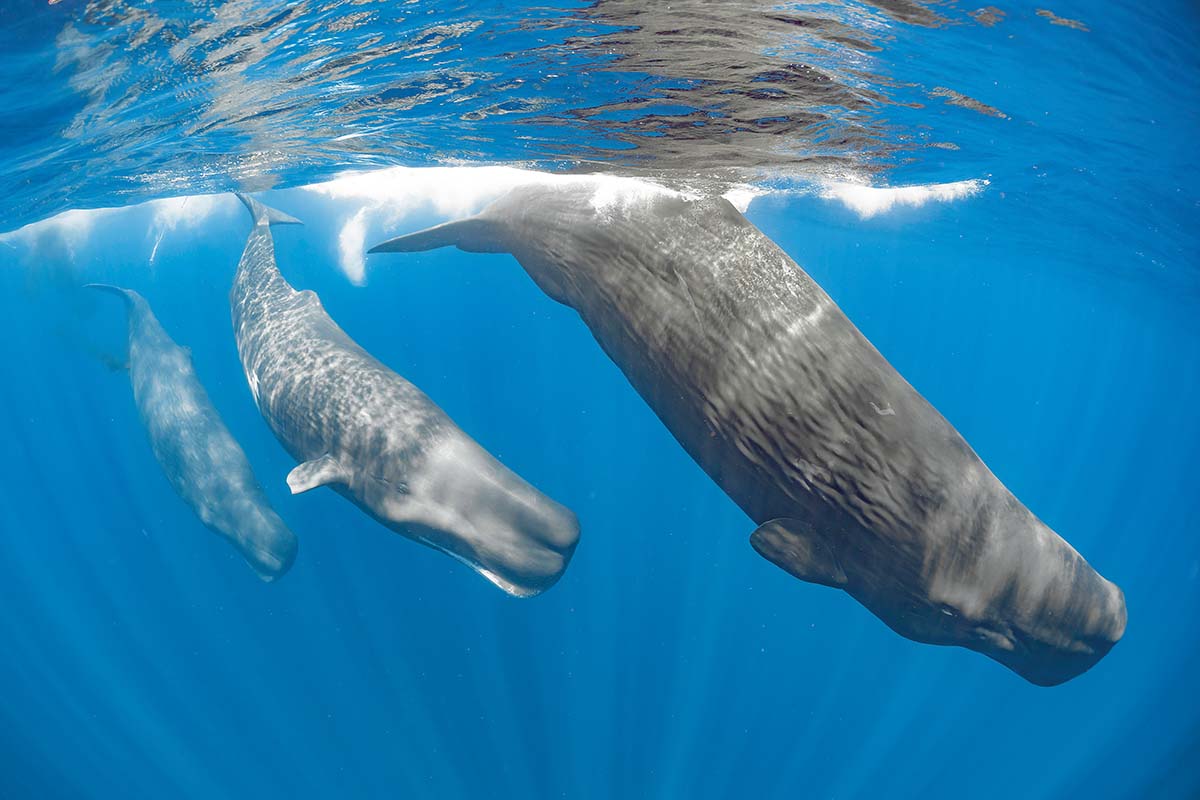

Underwater photographer Douglas David Seifert reflects on documenting a life beneath the waves

By

Underwater photographer Douglas Seifert has been taking photos beneath the waves for 40 years, ever since a childhood spent on Florida’s beaches encouraged him into the water. But even after all this time, getting the perfect shot is rarely easy. ‘I’ve had a lot of close calls,’ he says. ‘Honestly, I usually spend about ten months a year out in the field – at least I did pre-pandemic – and I’m nearly killed at least once a month. I would be in a dodgy anti-shark cage with a great white shark outside and it would come barrelling into the bars. The bars would break at the weld and I’d have the nose of a shark pushing me against the back of the cage!

‘I’m not really a risk taker,’ he adds, ‘but sometimes there’s a balance between risk and reward. I’m very determined that I’m going to capture the animal’s presence – I don’t want to use the term personality, because they’re not people – but they do have their own innate qualities that are unique to each individual and trying to capture that is a matter of observation.’

For Seifert, this trick of careful observation applies to any underwater creature, all of which can captivate. ‘At the beginning of my career, I was known for photographing sharks and whales, and I was very happy doing that – it’s very exciting,’ he says. ‘But there are so many other things in the ocean and my interests are with everything. I don’t care if I’m looking at a blue whale, or if I’m looking at a nudibranch, or a seahorse, I’m 100 per cent there – I’m living in the moment, I have no sense of time. I don’t feel any different about the things in the ocean than I felt about them when I was 12 years old or eight years old.’

This sense of wonder keeps Seifert in the water and provides the ultimate purpose for his photography at a time when all environments face huge threats. He has been World Editor of DIVE magazine for more than 20 years.

‘There can be no absolute purity,’ he says. ‘Let’s face it, all wildlife photographers are burning fossil fuels to get wherever they’re going. That’s why we really need to be good photographers and get our images out there – so we can keep people focused on the fact that nature is spectacular and worth preserving for itself. It doesn’t have to have an economic value; it has an intrinsic value that makes life worth living.’

Inspiration

As a child, I watched The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and then there was a milestone movie called Blue Water White Death that came out when I was about eight or nine years old. When it comes to photography, there’s an incredible photographer called Chris Nubert who did the first really great book of underwater photography. Everybody that was a diver just thought this was the most amazing book, and it still holds up to this day.

Purpose

I do it because, to me, it’s the most beautiful, fascinating part of life. I like to share that wonder with people that haven’t had the good fortune to go to these places and see these things. It’s about sharing this place I love the best with humanity, in the hope that humanity will see its value and protect it.

Advice

Anybody interested in underwater photography should develop really good skills at being a diver or snorkeler first so they’re not a risk to themselves and others, and so they’re not injurious to the marine life, or the environment. Only then should you take a camera because people put a viewfinder in front of their face and they lose all sense of where they are and what they’re doing. The animals and nature have to come first. Otherwise you’re doing it for the wrong reason and maybe you should play tennis instead.