Gloom about human-induced climate change and our impacts on flora and fauna can seem unrelenting. However, a new study offers hope and suggests that our efforts to protect nature can turn the tide on biodiversity loss

By

Is it working? It’s the question every biologist, conservationist and environmental campaigner must surely ask themselves during long nights of the soul when they wonder if projects intended to halt and reverse the decline of biodiversity across the planet actually make things better. The answer, it turns out, is, generally, yes. But not always. A groundbreaking review, ten years in the making, has assessed hundreds of conservation projects across the planet, some dating back to the 19th century, and found that the overall impact of conservation is positive and significant. In two-thirds of cases, conservation either improved biodiversity or at least halted declines.

A RAY OF LIGHT

Involving scientists from dozens of research institutions, the study, entitled The positive impact of conservation action, is the first of its kind to look across the globe and through time, reviewing 665 trials of conservation projects going back as far as 1890 and as recent as 2019. A range of conservation interventions targeted at species and ecosystems were examined, including invasive species control, habitat loss reduction and restoration, and protected areas. The research was rigorous: researchers whittled through the trials, selecting only conservation measures where there were at least five studies, thereby narrowing the margin for error.

The findings of the meta-study offer a ‘ray of light’ for those working to protect threatened animals and plants, according to those involved. ‘The message is that conservation works,’ says Thomas Brooks, chief scientist at the World Conservation Union, which facilitated the funding of the study by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). ‘We were surprised by the findings, especially because when you constantly read headlines about biodiversity loss and extinctions. It would be easy to think we are losing the battle,’ adds Penny Langhammer, lead author of the study and executive vice-president of the conservation organisation Re:wild. ‘Not only does conservation improve biodiversity, but when it works, it really works.’

The most successful approaches include schemes on farmland that increase the number of breeding waders. Targeting and eradicating invasive species was also successful. Breeding rates for loggerhead turtles and terns increased after successful predator management targeted invasive racoons and wild boar on Florida’s Barrier Islands. Turtle nest predation was just 16 per cent where predators were targeted, compared with rates up to 74 per cent on islands where no action was taken. Conservation efforts in Guyana reduced deforestation rates by 45 per cent, equivalent to saving around 13 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. The creation of protected areas and indigenous lands were shown to significantly reduce both deforestation rates and fire density in both Guyana and the Brazilian Amazon. Satellite-based maps of land cover and fire occurrence showed that rates of deforestation were 1.7–20 times higher and human-caused fires occurred four to nine times more frequently outside indigenous reserves and protected areas. Many indigenous reserves prevented deforestation completely, despite high rates of deforestation along their boundaries.

Conservation action has also clearly prevented extinctions. The review of projects found that intervention had prevented up to 32 bird and 16 mammal extinctions since 1993. Without conservation action, extinction rates would have been 4.2 times greater, the study found. Species saved from the abyss include Spix’s macaw, the Guam kingfisher, the scimitar-horned oryx and Przewalski’s horse.

DAMAGE LIMITATION

The impacts of intervention weren’t always so clear and what constitutes success depended on what the aims were, according to the report’s authors. In the Congo Basin, deforestation rates were 74 per cent lower in logging concessions under a forest management plan (FMP) compared with concessions without an FMP. The approach clearly made the impacts significantly less damaging but deforestation was still taking place.

Some measures yielded both negative impacts and unintended consequences. A marine protection area (MPA) established off New South Wales, Australia, aimed to increase biodiversity and protect White’s seahorse. In practice, the ban on commercial fishing enabled predators such as octopuses and sharks to flourish, leading to a decline in a favoured prey item – White’s seahorse. Such scenarios show the need for caution and for impacts on secondary species to be taken into consideration with such conservation projects, says Brooks. ‘Maybe it’s okay if the seahorses were being eaten within the protected area, if they were doing fine elsewhere. You would expect the larger species that are more sensitive to fisheries to do better within an MPA.’

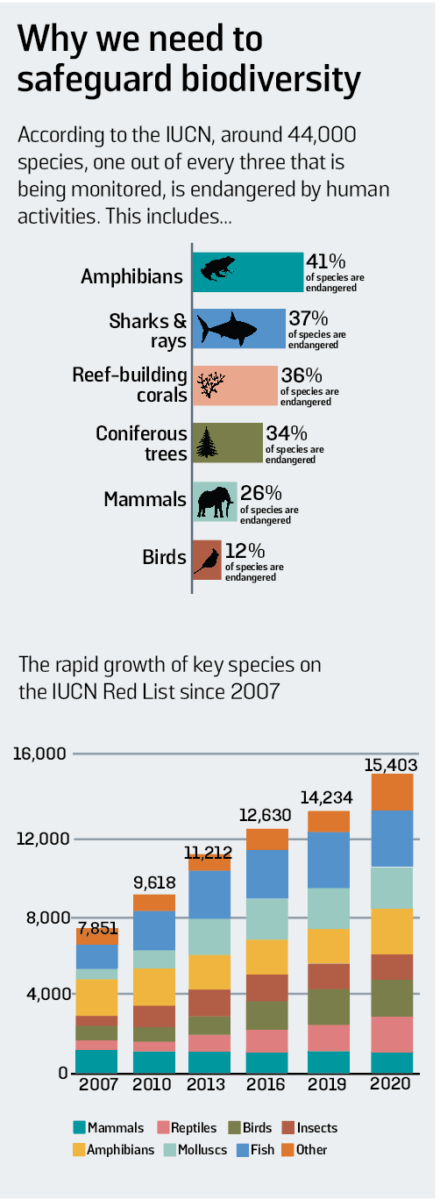

Unquestionably, biodiversity is under huge anthropogenic pressure. According to the IUCN, around 44,000 species, one out of every three species monitored, is endangered by human activities, including 41 per cent of amphibians, 37 per cent of sharks and rays, 36 per cent of reef-building corals, 34 per cent of conifers, 26 per cent of mammals and 12 per cent of birds. Earth’s ‘normal’, or background, extinction rate is thought to be somewhere between 0.1 and one species per 10,000 species per 100 years. Katie Collins, curator of benthic molluscs at the Natural History Museum, has said that the current rate of extinction is between 100 and 1,000 times higher than this pre-human background rate of extinction, a figure she described as ‘jaw-dropping’ and that’s widely attributed primarily to climate change, habitat loss and the spread of invasive species.

DOUBLING UP – A CARIBBEAN SUCCESS STORY

A key takeaway from the ten-year study into biodiversity methods was that combining different interventions will typically lead to mutually reinforcing and beneficial effects. In a project supported by Re:wild, the eradication of invasive species, combined with a protected area, has driven the transformation of a Caribbean island once compared to a moonscape.

When Redonda was first documented by Europeans in 1493, it was full of life, but colonisers introduced rats that preyed on native wildlife, while feral goats left behind by guano miners overgrazed flora. As the vegetation disappeared, soil and rocks slid into the sea, ultimately choking the coral reefs surrounding the island.

Following the removal of the invasive rats and feral goats in 2017, Redonda started to spring back to life. Vegetation has increased by more than 2,000 per cent, 15 species of land bird have returned and numbers of endemic lizards found on the island have increased by more than four-fold. The population of Redonda ground dragons – a critically endangered lizard – has increased 13-fold in just the past seven years.

The largest marine protected area in the eastern Caribbean was also established in the surrounding waters. Guano from the island birds has provided nutrients for the reefs. The new protected area – named the Redonda Ecosystem Reserve – is one of the biggest protected areas in the Caribbean and covers almost 30,000 hectares of land and sea, including the entire island, its seagrass meadows and a 180-square-kilometre coral reef.

Learning from previous studies, Re:wild, together with other partners, such as Fauna & Flora, is implementing strict biosecurity measures to guard against any future invasions. They are also supporting long-term monitoring and are planning the reintroduction of native species that can’t find their own way back to the island, such as iguanas and burrowing owls.

BOOST FOR FUNDING

The report is welcome because if international agencies – the UN and the World Bank, among others – are going to ask governments, philanthropists, charities and other donors to commit the vast sums required, they need to provide evidence that it’s worthwhile. Proving that action was better than not intervening was crucial, according to Brooks. ‘The fundamental thing about the paper is that it shows the importance of measuring impact,’ he says. ‘It’s the first time there has been a systematic review looking across the entire conservation literature.’

The study provided robust assessment of this key point, as the projects selected for assessment were specifically chosen because they had a counterfactual – the project was set up with what might be called a ‘control’ equivalent, that is, doing nothing. ‘If a financial adviser told you you’d get a 66 per cent return on your investment you’d grab it,’ says Langhammer.

Paul De Ornellas, chief adviser for wildlife at WWF-UK, feels the need for justifying outcomes to donors has become less important as awareness of the threats is increasingly better understood at corporate level. ‘It’s not the case that such projects are simply nice to have,’ he says. ‘Corporations are recognising that we all need clean air and water, and healthy soils, that their own commercial risks are linked to biodiversity. It’s no longer a niche conservation interest.’

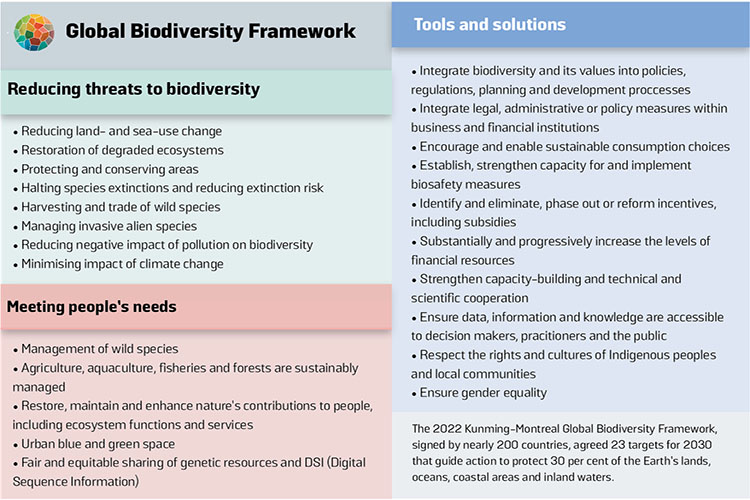

GOALS AND TARGETS

Efforts to address biodiversity loss take place within an overarching structure of international frameworks and agreements, which mostly focus on deadlines covering the next 25 years. The 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), signed by nearly 200 countries, agreed four goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030 that guide action to protect 30 per cent of Earth’s lands, oceans, coastal areas and inland waters (see the panel on Page 42). It sets out the need to reduce harmful government subsidies by US$500 billion annually and cut food waste in half. Other related targets are aspirational rather than specific, such as enhancing the resilience of all ecosystems, halting the extinction of threatened species and maintaining genetic diversity within populations of wild and domesticated species by 2050. Similar targets are echoed in the 17 sustainable development goals presented in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. ‘The GBF provides a direction of travel,’ says De Ornellas. ‘It’s not a legal mechanism, but in a world without the GBF there would be no overarching framework – we would be pushing against a much more difficult obstacle. Countries need to take the targets and translate them into national biodiversity action plans. That’s when the rubber really hits the road.’

A heartening finding of the study was that we’re getting better at conservation and learning from our mistakes. While a third of conservation projects had no effect or an adverse effect, their success rate is increasing over time. ‘Studies from long ago had a higher risk of failure than those done recently,’ says Brooks. ‘It’s an indication that we should be expecting to see – that we are getting better over time. We should be, as sophisticated techniques arrive and we learn from failures.’

One lesson learnt, argues Langhammer, has been the change in culture of conservationists and international agencies and charities, a shift that has led to less emphasis on donors calling the shots on projects. ‘We have clearly been learning as we go and it’s definitely the case that over time, conservation efforts have learned to include and be led by local, Indigenous people who know best how to be effective,’ she says.

Another determining factor in the effectiveness of projects is ensuring that they’re backed by meaningful legislation. ‘We need to make sure protected areas are properly protected. Otherwise, they are just lines on a map,’ says Langhammer. ‘These are really effective conservation measures, but not if human encroachment and poaching continue.’ Where projects didn’t work, it’s essential that scientists ‘learn from failure’, says Brooks.

‘Nobody gets everything right first time,’ he adds. ‘It’s important for the conservation community to understand why things go wrong.’ One example of this that caught Brooks’ eye was the removal of invasive algae species from coral in India’s inshore waters. Tackling the invasive algae in the marine environment backfired as it simply made it more vigorous in its colonisation of reef and coral systems; its removal actually facilitated its spread, as plants were broken up and distributed over a wider area, where they began to recolonise. ‘The report shines a light on changes from 30–40 years ago,’ agrees De Ornellas. ‘There’s a much greater focus on what the evidence says we do well and to learn from what doesn’t work.’

SCALING UP THE GLOBAL SOUTH

A counterintuitive but positive message from the study concerns the under representation of biodiversity projects in the Global South. Just under half the projects reviewed were conducted in South America, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, despite the fact that, as Brooks notes, ‘so much of the concentration of global biodiversity is in the tropics.’

In large part, this is because funding for conservation in the Global South has been historically under represented and disproportionately doled out to support projects in the Global North. The report found that in terms of geographic breakdown, the effects were positive and significant on all continents, with outcomes achieving similar rates of success across the planet. ‘It’s a top-level message of the entire piece of work – conservation works but we don’t do enough of it,’ says Brooks. ‘If we do more of it in the Global South, where the hotspots are, it can make an incredible difference. We would like to see movement when it comes to conservation projects in the Global South. The funding for projects there needs to be sufficient – then we can reverse the decline.’

The study provides the strongest evidence to date that conservation actions are successful but require transformational scaling up to meet global targets. Tellingly, if perhaps unsurprisingly, it found that multiple types of conservation actions are usually beneficial. Conservation was particularly effective when two or more approaches were combined, especially when it came to protected areas, payments for environmental services, invasive alien species eradication, sustainable use of species, control of pollution, climate change adaptation and sustainable management of ecosystems. Targeting invasive species and introducing protected areas, if implemented meaningfully, yield good outcomes, the authors say. Langhammer’s Re:wild has seen a twin-track approach in its work in relation to the Caribbean island of Redonda (see box on page 49), a former moonscape now teeming with biodiversity.

MORE CASH PLEASE

Around US$121billion a year is currently being invested in conservation worldwide, a sum much lower than what’s needed and representing barely 0.25 per cent of global GDP. The GBF calls for US$200billion per year from public and private sources. Often, these projects need to take place in countries where national governments have other funding priorities. Last year, the University of Oxford’s Conservation Research Unit reported that almost all of the remaining African lion ranges are within countries that rank in the 25 per cent poorest countries in the world.

Conservation projects can only succeed in the long term if accompanied not just by international legislation but by a shift in the protocols of international trade. ‘Species risk is closely linked to global trade,’ says Brooks. ‘Global trade is responsible for around one-third of the global extinction rate. Beef moves from Argentina to North America, and coconut oil from southeast Asia to Europe. We need to change patterns of consumer behaviour, shift the trade to sustainably produced beef and coconut oil.’ There’s a need, says Langhammer, to eradicate what she describes as ‘perverse subsidies’, which do nothing to discourage bad practices, such as deforestation or over-harvesting, in commodities such as soy, fisheries or agriculture.

‘We need to address the underlying factors, such as unsustainable production and fossil fuel subsidies,’ she says, pointing to the disparity in funding: fuel subsidies in 2023 were US$7 trillion, 13 times the amount needed to reverse biodiversity loss.

CAPTIVE BREEDING

Captive breeding has generally endured a poor reputation, often criticised as a means for zoos or wildlife groups to justify their funding with projects that, outside cages or sanctuaries, are unlikely to scale up in the real world. Commercial captive breeding has come in for even greater criticism, with fish farms widely associated with pollution, high mortality and impacts on wild species. The meta-study suggested that, when managed judiciously, captive breeding has strong merits and cited research into Chinook salmon in the northwest and northeast Pacific published in 2011. Two complete generations of Chinook salmon were tracked with molecular markers to investigate differences in reproductive success of wild and hatchery-reared fish spawning in the natural environment. Results showed a clear demographic boost to the wild population when supplemented by hatchery-reared salmon. On average, fish taken into the hatchery produced 4.7 times more adult offspring and 1.3 times more adult grand-offspring than naturally reproducing fish. Researchers also found that fish chosen for hatchery rearing didn’t have a detectable negative impact on the fitness of wild fish by mating with them for a single generation. One of the keys to success, they found, was that the original hatchery-reared fish had to be sourced from 100 per cent local, wild-origin brood stock, rather than from fish farms.

ADDRESSING THE UNDERLYING SYMPTOMS

Brooks is confident the report will act as a catalyst and a game-changer but feels a wider, coordinated approach will be necessary to truly reverse biodiversity loss. ‘There are few conservationists who aren’t optimistic and we have been heartened by the interest in the report. It will really help to strengthen further impacts,’ he says. ‘We need more conservation investment because we know that, typically, it works – 16,000 locations have been identified as key biodiversity sites, but only 40 per cent of these are protected. That’s an enormous shortfall. We need to scale up.’

The root causes of the global loss of biodiversity need to be addressed, warns De Ornellas. ‘In addition to classic conservation, we need to look at the drivers of habitat loss – over-exploitation of wildlife, over-extraction, logging, over-consumption, fisheries and hunting,’ he says. Brooks agrees. ‘We’ve got to address them, push sustainable development, alleviate poverty, stress the importance of peace, security and justice. We have powerful agencies, such as the GEF, social movements pushing for positive change. We have the tools; most of the pieces that we need are falling into place.’

Above all, says Langhammer, national leaders have to demonstrate that they have the appetite to build on conservation successes. ‘It requires much greater political will from countries and leaders, especially in the Global North,’ she says. ‘I’m an optimist, even more so after working on this study; I was really encouraged by it. We cannot overstate the finding that conservation works.’

Contrary to the background narrative that we have left it too late to act, De Ornellas argues that the report shows the opposite. ‘It’s easy to feel that the world has gone to hell in a handcart but the report and the CBD show the ambition to bend the curve and start turning things around for the better by 2030. We have the opportunity and the knowledge to do that. But the longer we wait, that window starts to narrow.’