Discover more about the hidden environmental cost of space junk and CO2 entering our atmosphere due to space exploration

By

Space exploration is booming — but with it comes a growing environmental cost here on Earth.

In 2023, the global space economy was valued at an estimated US$630 billion, creating jobs, driving technological innovation, and supporting essential services such as navigation and communication. Yet every rocket launched leaves behind a footprint in the stratosphere — and its effects are larger than many realise.

The hidden impact of rocket launches

In 2019, rocket launches released 5.82 gigagrams of CO2 into the upper atmosphere — comparable to around 5,820 transatlantic return flights. At stratospheric altitudes, these emissions linger far longer and do more harm, with pollutants such as black carbon contributing disproportionately to ozone depletion and climate disruption.

Satellite megaconstellations, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, account for around 40 per cent of rocket launch emissions — a share expected to rise as demand for global broadband and Earth-monitoring capacity expands.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

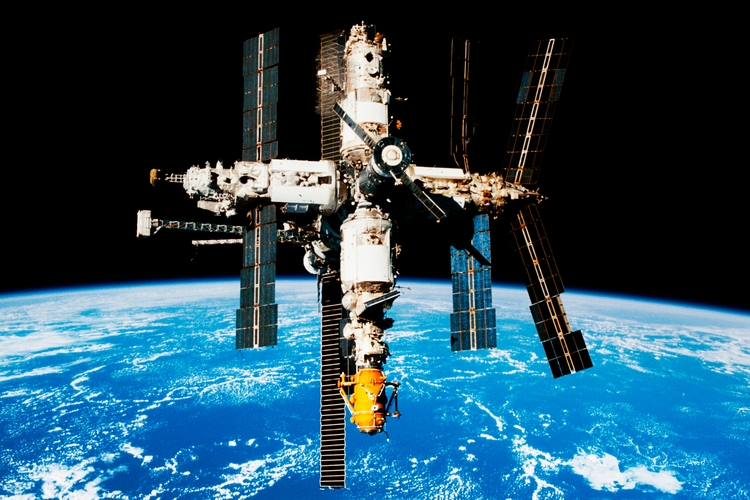

The scale of activity in orbit has accelerated dramatically over the last decade. In 2015, around 220 objects were launched into space. By 2023, that number had risen to nearly 2,900 — a more than tenfold increase in less than ten years.

The United States dominates, accounting for 79 per cent of all launches in 2024, but the UK has also emerged as a significant player. In 2016, Britain launched just a single object; by 2021, it was responsible for 289 launches in one year.

This shift is underpinned by a policy push: the government’s National Space Strategy (2021) and plans for new launch sites in Cornwall, Glasgow, and Shetland. Scotland’s high northern latitudes, in particular, make it ideal for sending satellites into polar orbits, which are increasingly in demand for climate monitoring and global communications.

Falling back to Earth

Space debris is another pressing issue. Roughly 300 objects re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere each year — from failed rocket fragments to decommissioned satellites. While most burn up, they release particles of aluminium, copper, lithium, and other metals, altering atmospheric chemistry and potentially undermining the ozone layer.

Researchers at the University of Southern California estimate that, once all planned megaconstellations are deployed, 360 tonnes of aluminium oxides will be released into the atmosphere annually — a staggering 646 per cent increase over natural levels.

Since 1971, more than 263 spacecraft have been deliberately crashed into Point Nemo, a remote oceanic location about 2,688 kilometres from the nearest land (the Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific).

Looking ahead

Space offers humanity extraordinary opportunities: from global connectivity to insights into climate change. However, as the industry expands, its environmental footprint also grows.

The question for policymakers, companies, and researchers is whether we can innovate our way into a truly sustainable space age — one where exploration beyond Earth doesn’t come at the cost of the planet we call home.