As coastal development continues to grow, research begins to reveal the depth of our light pollution problem: artificial light may impact marine organisms that live deep below the surface

By

Life has evolved a sensitivity to moonlight. In the oceans, the waxing and waning of the lunar cycle drives a lot of activity, from the nightly migrations of the tiny sandhopper to the mass spawning of coral reefs. Over the past 100 years, however, the daily and seasonal cycles of natural light have been disrupted by the introduction of artificial lighting in our homes and on our streets. Today, more than 80 per cent of the world lives under a light-polluted sky. We already know that artificial light has an impact on the behaviour of bats, insects and birds but, until recently, it was believed that too little light penetrated deep enough into the ocean to affect marine life.

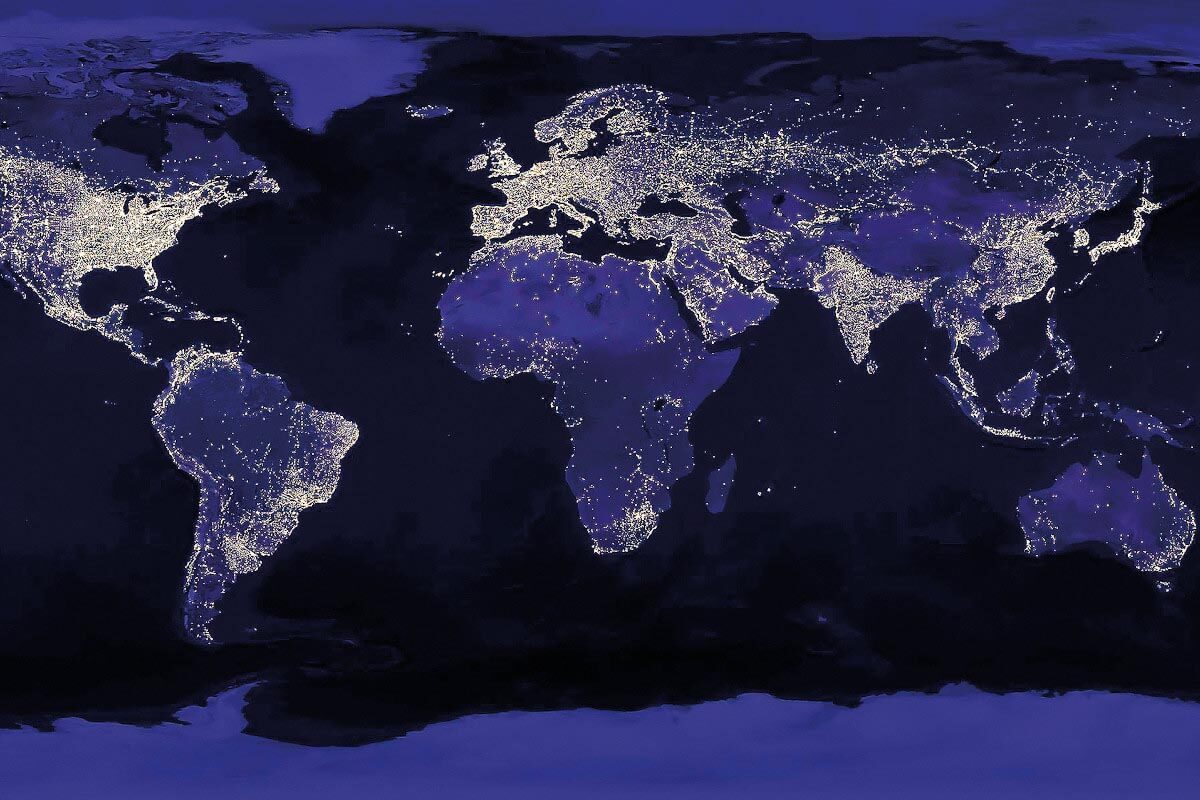

Tim Smyth, a researcher at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, admits that he, too, was sceptical at first, ‘because artificial light levels are a million times less intense than sunlight’. But consultation with colleagues specialising in marine conservation, and some basic back-of-the-envelope calculations, convinced him that this merited further study. The resulting research, a collaboration by an international team of scientists, has produced the first global atlas to depict the extent of light pollution in underwater habitats. Its most significant finding is that at a depth of one metre, 1.9 million square kilometres of the world’s coastal waters are exposed to a level of artificial light that triggers responses in marine life.

The researchers used the well-known ‘atlas of artificial night sky brightness’ developed by physicist Fabio Falchi and colleagues, along with other data such as satellite imagery. They were able to determine where the world’s oceans were being exposed to artificial light and how much of it. Next, they needed to know what light levels could be detected by marine organisms. Copepods – microscopic crustaceans found in nearly every marine habitat – were the ideal subject, being very sensitive to light (they dive deeper to avoid it, reducing the chance that they’ll be seen by predators). It’s the copepod’s light sensitivity, Smyth says, that was used to determine a critical depth at which artificial light has a significant impact on marine life.

In the most heavily light-polluted regions, the study estimates that this impact is causing disruption to every trophic level, from phytoplankton upwards. The most exposed waters – the Persian Gulf, the eastern Mediterranean and the North Sea – are in areas with both offshore development and coastal urbanisation. ‘There’s an increasing amount of urban development along coasts,’ says Smyth. ‘When you look at the top ten megacities in the world, eight are classed as coastal.’ He hopes that with more research, the atlas can act as a guide to mitigating the ecological effects of artificial light, particularly when it comes to illuminating our increasingly LED-lit coastal cities. ‘LED lighting has been a game changer in terms of its carbon footprint, but the flip side of that is that the blue wavelengths penetrate much deeper.’

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!