Concerns about the ozone hole have diminished as levels of ozone-depleting man-made chemicals have fallen – but research is still ongoing

By

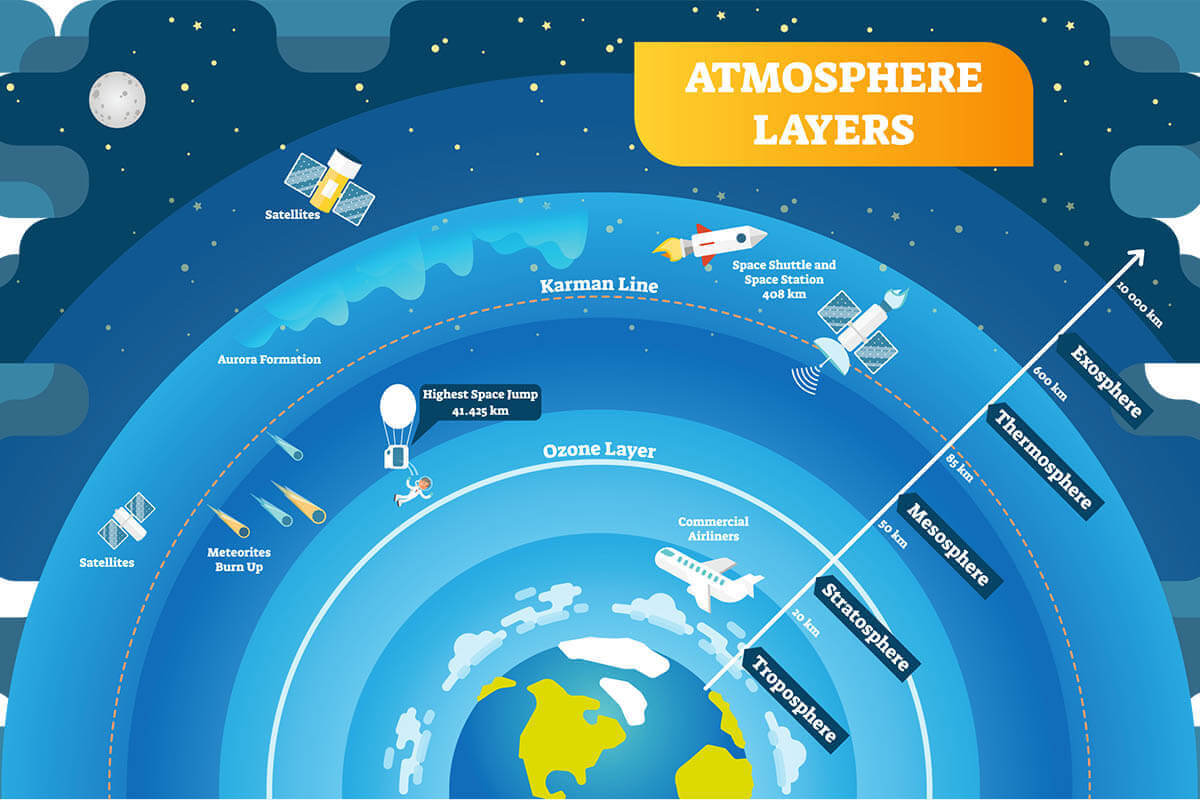

The ozone layer is a natural, protective layer of gas in the stratosphere (the second major layer in the Earth’s atmosphere). It lies approximately 25 miles above Earth’s surface.

Its name comes from the relatively high concentration of ozone (O3) – a highly reactive molecule comprised of three oxygen atoms – present in the layer compared to other parts of the atmosphere, although this concentration is still small in relation to other gases in the stratosphere.

The ozone layer shields life from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation which can cause skin cancer and cataracts, suppress immune systems and also damage plants.

Ozone depletion

In 1976, atmospheric research revealed that the ozone layer was being depleted by chemicals containing chlorine and bromine. These include chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were commonly found in air conditioners, refrigerators and spray cans; halons, which are found in fire extinguishers; and methyl bromide, which is used to kill weeds, insects and other pests.

In 1985, researchers at the British Antarctic Survey discovered a hole above Antarctica (later known as the ozone hole).

The discovery led to concerns that damage to the layer could threaten life on Earth, leading to increased skin cancer in humans and other ecological problems.

These concerns eventually led to the adoption of the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which bans the production of CFCs, halons and other ozone-depleting chemicals. The ban came into effect in 1989.

As a result of the protocol, ozone levels stabilised by the mid-1990s and began to recover in the 2000s. Recovery is projected to continue over the next century, and the ozone hole is expected to reach pre-1980 levels by around 2075.

In 2019, NASA reported that the ozone hole was the smallest ever since it was first discovered in 1982.

Antarctica

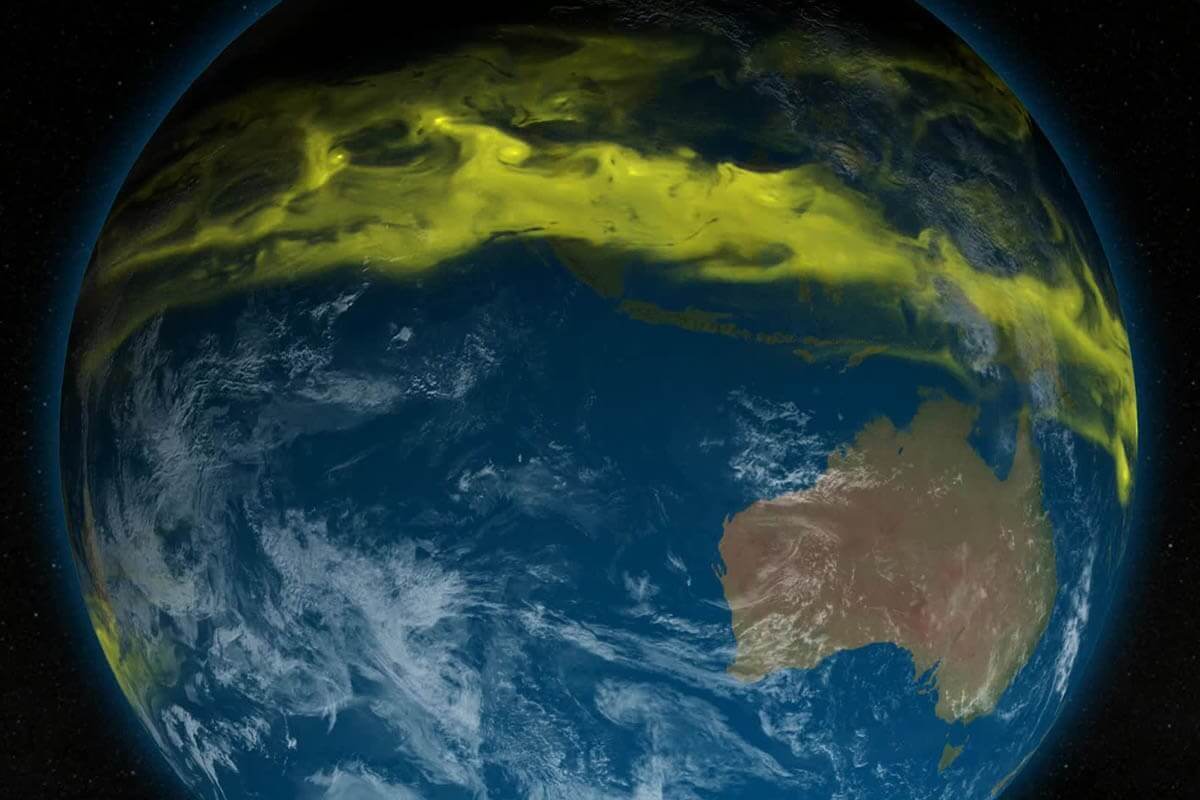

The ozone hole is an annual thin spot that forms in the ozone layer over Antarctica in mid-September and October.

The hole forms when chlorine and bromine, derived from man-made compounds, mix with polar stratospheric clouds. These clouds form during polar vortexes – a band of strong winds circling the pole – which occur where temperatures drop to at least -78 °C. They are made of a mixture of water and nitric or sulphuric acid. As the chlorine and bromine become trapped by the winds of the polar vortex, chemical reactions occur on the surface of cloud particles. This turns the otherwise harmless chlorine and bromine into chemicals capable of destroying ozone.

During years with normal weather conditions, the hole typically grows to a maximum area of about eight million square miles (20.7 million square kilometres) in late September or early October (around double the size of Europe).

2019 was an unusual year, and saw the smallest ever ozone hole since it was first discovered in 1982. The hole reached its peak extent of 6.3 million square miles (16.4 million square kilometres) on 8 September and then shrank to less than 3.9 million square miles (10 million square kilometres) for the remainder of September and October, according to NASA and NOAA satellite measurements.

The Arctic

Ozone holes rarely form at the North Pole and they are typically short-lived. Temperatures in the Arctic don’t regularly drop as low as they do in Antarctica, which means ozone depletion occurs to a smaller extent. Prior to 2020, the last Arctic ozone hole occurred in 2011.

In late March 2020 scientists spotted signs of a hole forming in the Arctic. The hole reached record dimensions, but by 28 April it was announced that the hole had closed. The rare event was caused by a polar vortex which led to the formation of high-altitude clouds in the region. The clouds mixed with man-made chlorine and bromine which then ate away at the ozone. The resulting hole was roughly three times the size of Greenland, although was still considered small by Antarctic standards. The hole closed when temperatures increased, breaking down the Arctic polar vortex.

Due to its location the hole didn’t pose any danger to humans. This would only have been the case if it had moved further south over populated areas, such as southern Greenland.

It is too soon to tell whether the hole represents any kind of trend, or why exactly it happened. In a press release, Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland said: ‘This year’s low Arctic ozone happens about once per decade. For the overall health of the ozone layer, this is concerning since Arctic ozone levels are typically high during March and April.’

Ozone layer and climate change

Many misconceptions exist around the ozone layer. One of the biggest is that the ozone hole drives global warming.

While some extra UV rays from the Sun do slip through the hole, the effect is minimal. In fact, the net effect of the hole is to cool the stratosphere rather than warm the troposphere (the lowest level of the atmosphere that reaches the Earth’s surface). This is because ozone is a greenhouse gas that traps heat, and its destruction therefore has a cooling effect.

This doesn’t mean that the ozone hole has no effect on wider climate change. Scientists have recently discovered that the hole has been affecting climate in the Southern Hemisphere. The colder stratosphere has resulted in faster winds near the pole, which can have impacts all the way to the equator, affecting tropical circulation and rainfall at lower latitudes.

In addition, some scientists have suggested that climate change could affect development of ozone holes at the North Pole. Scientists have speculated that climate change may have set the stage for a colder, and thus more powerful, polar vortex, though research is still in the early stages.

Further research

Research into the ozone layer is ongoing. In May 2020 researchers at the University of Southampton published a study in Science Advances which showed that an extinction event 360 million years ago, that killed much of the Earth’s plant and freshwater aquatic life, was caused by a brief breakdown of the ozone layer. The scientists found evidence that high levels of UV radiation collapsed forest ecosystems and killed off many species of fish and tetrapods (our four-limbed ancestors).

The ozone collapse occurred as the climate rapidly warmed following an intense ice age. As ice sheets melted and global warming occurred, the increased heat above continents pushed naturally generated ozone destroying chemicals into the upper atmosphere. This let in high levels of UV-B radiation for several thousand years. The researchers suggest that the Earth today could reach comparable temperatures, possibly triggering a similar event.

Professor Marshall, lead author of the study, said that his team’s findings have startling implications for life on Earth today: ‘Current estimates suggest we will reach similar global temperatures to those of 360 million years ago, with the possibility that a similar collapse of the ozone layer could occur again, exposing surface and shallow sea life to deadly radiation. This would move us from the current state of climate change, to a climate emergency.’

The research suggests that there is little room for complacency. Despite the success of the Montreal Protocol, it is important to ensure that levels of CFCs and other pollutants never rise again. Equally, it is important to counter global warming by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases.