Find out more about blue carbon, why it is vital for the planet and how it can slow down the rate of climate change across the world

By

We’ve all heard of carbon – the fundamental building block of all human, animal and plant life. Greenhouse gases, such as methane or CO2, also contain an abundance of the chemical element.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

But what exactly is blue carbon, a term increasingly cropping up in news articles, scientific papers and research? Read on to find out more about blue carbon, its origins and how it helps the planet.

What is blue carbon?

In short, blue carbon is the term for carbon captured by all of the world’s oceans and coastal ecosystems.

The vast majority of blue carbon is carbon dioxide that has dissolved directly into the ocean. Smaller quantities of carbon are stored in underwater sediments, coastal vegetation and soils; carbon-containing molecules like DNA and proteins, alongside ocean life from whales to tiny phytoplankton.

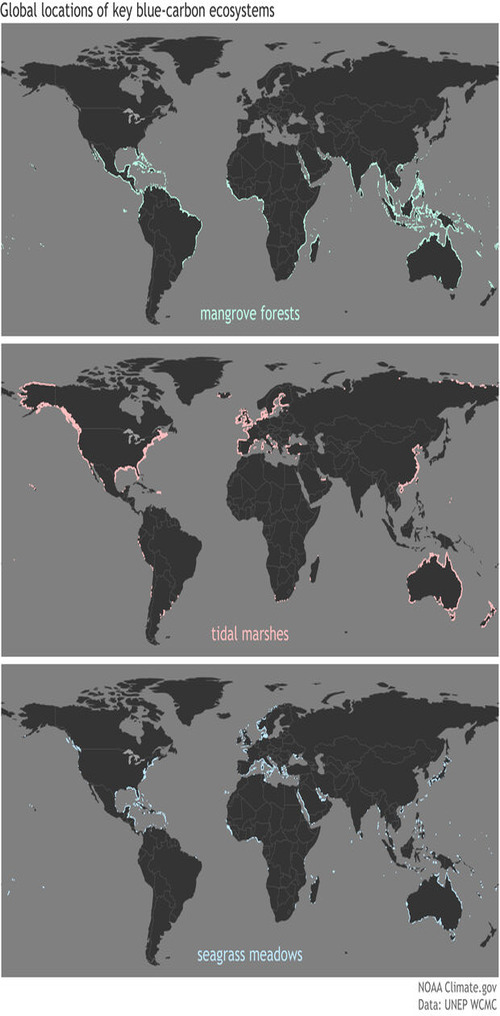

International agreements on curbing climate change have tended to focus their attention upon coastal blue carbon – carbon stored by saltwater ecosystems in vegetation and soils. In terms of total area, these ecosystems – the three main ones of which are salt marshes, mangroves and seagrass meadows – have an objectively small global footprint. Yet, their water-logged soils can provide a rich area as a carbon sink, burying more carbon per acre than a tropical rainforest could.

This heightened ability to store carbon is for two reasons. Firstly, their plants grow quickly naturally, and in the process, capture large amounts of carbon dioxide. As well as this, their soils are mainly anaerobic (do not have oxygen), so carbon dioxide is incorporated into soils, decomposing slowly over a time period of hundreds or even thousands of years.

As such, spread across every continent apart from Antarctica – and covering a territory almost double the size of the UK – seagrass meadows, mangroves and salt marshes are vital in reducing atmospheric carbon levels.

Seagrass meadows – around 82 species consisting of flowering plants that grow in salty marine environments – are particularly great at storing carbon. Accounting for just 0.1 per cent of the ocean seafloor, they store 11 per cent of the organic carbon buried deep within the ocean. Mangroves are also incredibly useful: trees, shrubs or plants growing in coastal swamps that sequester carbon at a rate ten times faster than a mature rainforest. Finally, salt marshes – dense salt-tolerant grasses, herbs or shrubs that grow between land and open salt water – offer another ample opportunity for carbon to be stored.

Collectively, the soils and vegetation in coastal ecosystems store between 10 and 24 billion metric tons of carbon. Each year, they add approximately 30 to 70 million metric tons to their soils. While it may sound like a hefty number, in reality, it is just a small fraction of the carbon dissolved directly into the ocean as CO2 (40 trillion metric tons).

In the UK, such ecosystems sequester and store around two per cent of the country’s annual emissions.

Why are coastal blue carbon sinks important?

Because coastal blue carbon sinks contain so much carbon, it is vital that these habitats are appropriately conserved. That’s because when these systems are damaged, a significant quantity of carbon is emitted back into the atmosphere, where it can contribute to climate change.

One way to slow down the impacts of climate change is to incorporate coastal wetlands into the carbon market by buying and selling carbon offsets. As such, a financial incentive is created for restoration and conservation projects, helping to alleviate state carbon taxes, which are instead aimed at discouraging the use of fossil fuels.

Essentially, such a scheme operates in a cycle: when fewer greenhouse gases are emitted, less pollution is created. As such, less pollution taxes create a benefit for the environment alongside financial benefits for the community carrying out restoration.

In particular, mangrove forests are also important in protecting coastal communities from flooding. According to a World Bank report, these ecosystems protect more than six million people from flooding annually, and prevent losses of $24 billion in productive assets.

How are coastal habitats being protected?

Around the world, many projects are underway to ensure coastal habitats can be preserved for generations to come. One major project is the idea of a carbon market in which a country or region’s activities to reduce emissions become currency that it uses to offset its own emissions, or to trade with other countries.

For example, in Florida, one research body is studying the feasibility of using a planned mangrove restoration to bring blue carbon credits to the market.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, data is being published on the carbon stored in Pacific Northwest tidal wetlands, with partners also filling in data gaps on carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions. In doing so, researchers aim to calculate the carbon-market value of various restoration projects.

Despite their plethora of uses for the benefit of the environment, coastal habitats storing vast swathes of blue carbon face intense development pressure. Since the 1800s, coastal development has led to the loss of 25 per cent of salt marshes worldwide. 30-50 per cent of mangrove forests have entirely disappeared since the 1940s, and 50 per cent of all seagrass meadows in the last 35 years alone.

Today, mangroves are continually decimated at a rate of up to three per cent per year, salt marshes at one to two per cent, and sea grasses at a remarkable seven per cent per year.

Worldwide, stopping seagrass destruction and degradation alone could save up to 650 million tons of CO2 emissions annually, approximately equivalent to the annual emissions of the global shipping industry.