In the aftermath of a devastating earthquake, Stuart Butler reports on a country torn apart by brutal civil war

The first tremor struck just after sunrise. Buildings swayed, cracks split across roads and terrified residents poured into the streets of Yangon, Mandalay and other cities. The March 2025 earthquake – the strongest to hit Myanmar in more than a century – ripped across the central regions, destroying homes and hospitals, severing communications and triggering landslides in the mountainous north.

In normal times, a natural disaster of such magnitude would spark a national relief effort, bolstered by international aid. But these are not normal times. In Myanmar – four years into a brutal civil war – the quake’s devastation collided with a country already stretched beyond its limits.

Humanitarian aid struggled to get through. The military junta only controls around a third of the country and even as trucks were waiting at the borders to bring in vital humanitarian supplies there were air strikes in rural areas controlled by the anti-regime National Unity Government (NUG). It’s feared the death toll could exceed 10,000 and vital infrastructure such as schools, hospitals and roads have been destroyed. Many doubt whether the country can recover from the scale of destruction while the civil war continues.

Myanmar has a long history of strife. For more than 50 of the past 60 years, a military junta has ruled the country. There have been a series of long-running ethnic insurgencies, with large swathes of the country under the control of rebel goups. However, in recent years things have become even worse. Yet another military coup in 2021 has resulted in Myanmar spiralling into full-scale civil war.

Today the rebel NUG controls most of the rural areas, while the cities are under military rule. In the ensuing fighting more than 6,000 civilians have been killed.

Recommended reads:

One family’s account epitomised the trauma of the past four years. ‘It was 27 March 2021. Myanmar Armed Forces Day. I’d just got into town when I got the phone call from my sister,’ Taurus recounts to me in short, sharp sentences. ‘She told me that soldiers had surrounded the house. They were firing bullets and tear gas and screaming at everyone inside to come out into the street. I rushed home as quickly as I could, but I couldn’t get there fast enough.’

On the morning of 1 February 2021, a convoy of military vehicles had raced towards the parliament buildings in Naypyidaw, the capital. A military coup was underway and tentative moves towards a form of democracy were about to be snuffed out.

Taurus’s life story is typical of so many Burmese of her generation. ‘I’m one of nine siblings. Our family was very poor. No matter how much we all worked, we never had enough money. My mother had a good job – she was a principal at a primary school – but my father never really worked much. He was an alcoholic and quite rough. He died in 2004. I didn’t have an easy childhood and because we were so poor, all us children had to work from a very young age.’ Taurus, now 45, sighs at the memory. ‘I started work at the age of 11. I carried bricks at construction sites. It was very hard and the pay was bad.’

The largest country in mainland Southeast Asia, Myanmar has spent most of its life since independence from Britain in 1948 under the shadow of military dictatorship. For decades, the military junta ensured that the people of Myanmar had little contact with the rest of the world.

Development stagnated and Myanmar quickly fell behind most of its neighbours in terms of human and economic progress. For years, pro-democracy activists led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi called for free and fair elections.

Her resistance to the junta led to years under house arrest, while thousands of lesser-known Burmese endured far worse in Myanmar’s prison system. But things changed dramatically in 2010, when Aung San Suu Kyi was released and the junta announced elections would be held. In 2015, her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), claimed a landslide win. The years of military oppression appeared to be over.

International investment and development projects flooded in. New buildings sprang up, businesses opened, international chains moved in, and cars swamped the once-quiet streets.

According to Taurus, ‘When Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD took over, we were all so happy. I thought Myanmar would become like other countries in Southeast Asia. The country developed so fast over those six or seven years. Everything was changing. Everyone was excited and optimistic for the future.’

However, behind the scenes, the military had never truly accepted this new reality. And so, three months after being systematically defeated in the November 2020 elections, it launched its surprise coup. Aung San Suu Kyi, along with virtually the entire NLD leadership, was arrested. Taurus takes up the story. ‘It was early morning and I was still in bed when I heard about the coup. I didn’t believe it. I thought they were playing games with us. It was like my whole life had been taken away from me. I’m a mother and I’d thought my son’s future was bright, but suddenly everything was dark again. I called a friend and we went into central Yangon and told people not to believe the news. We told them it wasn’t true. I returned home crying. It was like I’d gone crazy.’

Within days, peaceful protests broke out across Myanmar – soon met with a brutal crackdown. The protest movement morphed into armed resistance, which has since combined with several of the ethnic rebel armies. Taurus was quick to join the demonstrations.

‘When the protests started, I went every day. I even led a crowd protesting outside the Singapore embassy. At first, I was optimistic we could change things, but the military’s response became more violent. At one protest, some students were arrested. We went to the police station and shouted for them to be released. Military trucks full of soldiers surrounded us and started shooting. I ran and hid in a monastery. That’s when I knew the military wouldn’t give in.’

In late March, six weeks after the coup, Taurus’ world fell apart. ‘When I got back home, one of the soldiers pointed a gun at me and threatened to shoot if I got any closer. There was nothing I could do. The soldiers were destroying my home with my family still inside it. My 11-year-old son was trapped. I’ll never forget the moment he phoned me to say he thought he was going to die.’

The attack on Taurus’s family was part of a pattern repeated across Myanmar. Since the coup, the military has cracked down on any form of dissent; thousands have been jailed or killed, the economy has collapsed, public services have disintegrated and armed rebellion has erupted across the country.

Speaking to Geographical by phone from Thailand, Ben Dunant – editor of Frontier Myanmar, which has been operating from Thailand since the coup – describes life in the country today. ‘The economy has really died,’ he says. ‘There was a huge contraction of 18 per cent in the year after the coup. Some of this was due to Covid, but much was the result of the coup. Wages haven’t risen, but prices of day-to-day products have gone up a lot. People are cutting back on what they buy, and many families are being forced to skip meals. The education system has also been severely degraded, as has healthcare. There’s a shortage of medication in city hospitals, and in rural areas many health facilities have shut down.’

Dunant goes on to describe the terror of life under the military. ‘In regime-run areas, people are living under a very brutal system. There’s no room for dissent. You can be imprisoned and tortured just for a Facebook post criticising the military. Protests are still taking place in Yangon, but more in the form of flash protests. It’s extremely dangerous – these are cracked down on very quickly. But there are underground resistance groups, often young people, who do these flash protests.’

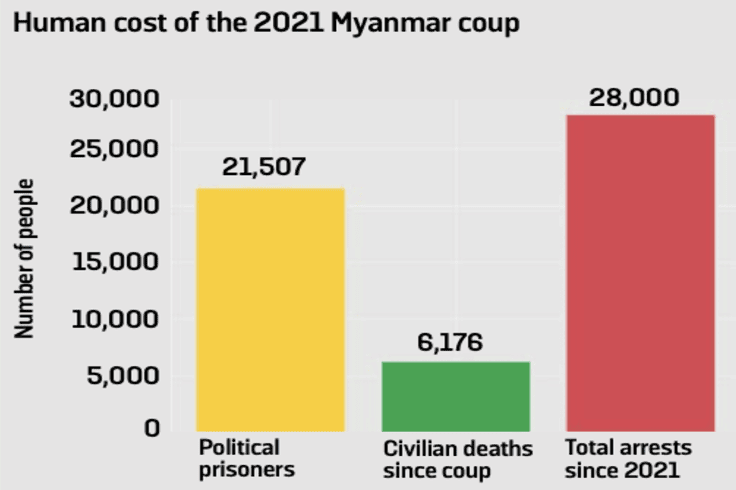

Anyone caught opposing the junta is likely to be severely punished. According to a January 2025 statement by Burma Campaign UK and the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), 6,176 pro- democracy activists and civilians have been killed by the junta (not including armed resistance fighters), more than 28,000 people – including 589 children – have been arrested for politically motivated reasons since the coup, and as of early 2025, 21,507 political prisoners remained in detention. Reports from human rights organisations document widespread torture, sexual violence and denial of medical care.

Aung San Suu Kyi remains imprisoned. In a closed-door trial widely condemned by international observers, she was sentenced to 33 years (later reduced to 27) for offences ranging from treason to corruption. She has not been seen publicly since, and her son, Kim Aris – who holds UK citizenship – has said he has been denied all contact with her and fears that her health is deteriorating.

In February 2024, the junta announced compulsory military service for all men aged 18–35 and women aged 18–27. The announcement triggered a wave of young people fleeing junta-controlled areas. David Eimer, a former Yangon resident and author of A Savage Dreamland: Journeys in Burma, tells us, ‘On the surface, life in Yangon and other cities under military control has a certain normality. But the military draft has made it very difficult for men of certain ages. If they go out on the street, they risk being grabbed and press-ganged into service, where they’re treated as cannon fodder.’

Taurus agrees. ‘It’s not safe for boys and men in Yangon now,’ she says. My son is 14, and I have to check constantly that he’s indoors. The military don’t care how old they are – they’ll just take them. As a mother, if my son can’t walk the streets safely, then I don’t feel safe.’

In recent months, the military has been losing ground to various resistance groups. It’s difficult to assess exactly how much territory the junta still controls, but a December 2024 BBC World Service investigation indicated the regime had lost partial or total control of around three-quarters of the country, including most areas bordering India, Bangladesh, China and Thailand. However, the military retains firm control over the major population centres and the central heartland.

Even after the earthquake at the end of March, the military continued to launch indiscriminate air and land attacks on rural villages in rebel-held areas despite announcing a ceasefire. Many are using makeshift paragliders with soldiers dropping bombs.

For many families, the toll has already been awful, ‘The soldiers were there most of the day, just shooting at my home,’ Taurus says, recalling the events of 27 March. ‘The sister who phoned me – they shot her twice in the stomach. They wouldn’t let an ambulance approach and she bled to death where she fell. They shot one of my brothers in the lung. They grabbed another sister, doused her in gasoline and tried to set her alight. All I could do was watch and cry.’

Fast-forward to early 2025 and, although the junta continues its campaign of repression, life had moved on for Taurus. ‘After hours of shooting, it suddenly stopped, and the soldiers left. I never really found out why they targeted us. The brother who was shot survived, but after he came out of hospital, he was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison. He was released in 2023 and now takes care of our mother. The sister they tried to set fire to survived, too, but her husband and eldest son were arrested in 2022 and sentenced to ten years for terrorism-related charges – the term the military uses for resistance members. She lives with me now.’

Taurus’s son, remarkably, was unhurt. ‘He returned to school in 2023 and is doing well. His favourite subjects are science and English. He’s mad about basketball – his dream is to play in the NBA.’

And Taurus? ‘I’m lucky. I fought hard to get out of poverty. I now have a good job that involves international travel – and a few weeks ago, I remarried!’ Taurus and her family remain in Yangon, but like the story of Myanmar itself, her story is far from over. ‘My dream is to retire to a peaceful place and live a quiet life. But I don’t think that can happen here.’ Since the earthquake we have not been able to contact Taurus.

Fact file

Area

6,578 sq km – roughly the size of France.

Population

About 54 million (2024), with major ethnic groups including Bamar, Shan, Karen, Rakhine, Chinese, Indian and Mon. The Bamar, also known as Burmese or Burmans, are the largest ethnic group with around 35 million people.

Cities

Yangon (5.4 million), Mandalay (1.2 million), Naypyidaw – the capital city – (1 million).

Religion

Buddhism (bout 88 per cent), Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and animism.

Languages

Burmese (official), with more than 100 languages spoken across ethnic groups.

Ethnicity

There are 135 recognised ethnic groups, with long-standing tensions between the Bamar- majority government and minority groups.

Military rule

More than 50 of the past 62 years under authoritarian military rule.

Poverty and economy

About 40 per cent of the population lives below the national poverty line; the economy shrank 18 per cent following the 2021 coup.

Myanmar’s GDP growth/contraction (2019-24)

Education

Many schools closed or defunct in conflict areas; literacy rate about 89 per cent.

Internet/freedom

Internet access restricted; widespread censorship; hundreds arrested for online speech.

Political prisoners (as of Jan 2025)

21,507 in detention; 6,176 killed since 2021 coup.

Rare earth boom

Myanmar has quietly become a major player in the global rare earth trade – and with it, a new front has opened in the country’s internal conflict. Rich in heavy rare earth elements such as dysprosium and terbium, which are critical for electric vehicles and wind turbines, Myanmar now supplies nearly half of China’s heavy rare earth imports.

Most mining takes place in Kachin State, particularly around the towns of Chipwi and Pangwa, near the Chinese border. These remote regions have seen a boom in extraction, often using environmentally destructive methods such as in-situ leaching. Deforestation, soil erosion and water contamination are common, with little regulation. This also poses serious health risks for the workers involved. Control of these lucrative sites has become a strategic objective for armed groups.

In late 2024, the Kachin Independence Army seized key mining areas, disrupting exports and pushing global rare earth prices upwards. The trade – estimated to be worth US$1.4 billion in 2023 – is increasingly seen as fuelling both the resistance and the regime.

Myanmar’s rare earths are more than an economic asset – they’re a geopolitical flashpoint. As global demand grows, the battle over who controls these minerals could reshape not just Myanmar’s war, but the global supply chain.

Ethnic wars

While the current civil conflict has captured international headlines, Myanmar’s landscape of rebellion is nothing new. For decades, a patchwork of bitter ethnic insurgencies has fought the central government, driven by demands for autonomy, cultural rights and control over resource-rich territories and opium production.

In the north, the Kachin Independence Army has waged intermittent war since 1961. Though a ceasefire was signed in 1994, hostilities resumed in 2011, especially around lucrative jade mines in Kachin State.

To the east, the Karen National Union is one of the world’s longest-running ethnic insurgencies, battling for autonomy since 1949. Despite a ceasefire in 2012, clashes have reignited since the 2021 coup, with Karen forces now aligning with newer anti-junta groups.

The Shan State Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army and other militias operate in Myanmar’s fractious northeast, where rivalries over drugs, trade routes and political influence have created a volatile and overlapping theatre of war.

In the west, the Arakan Army, formed in 2009, has become increasingly powerful, campaigning for greater self-rule in Rakhine State. Its rise coincides with international scrutiny over the military’s brutal campaign against the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group that, despite not being armed, was collectively punished and forcibly displaced.

These ethnic conflicts – complex, localised and deeply entrenched – form the backbone of Myanmar’s long-running internal war. Today, many of these groups have joined the wider resistance against the military junta, turning decades of fragmented struggle into a more unified rebellion.

Ethnic cleansing

The Rohingya, a Muslim minority in Rakhine State, have faced decades of discrimination in Myanmar, denied citizenship and basic rights. Tensions escalated in 2017, when a brutal military crackdown forced more than 700,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. UN officials described the operation as ‘a textbook example of ethnic cleansing’.

Despite international condemnation, few have returned. Refugee camps near Cox’s Bazar remain overcrowded and under-resourced, with hopes of repatriation fading amid Myanmar’s ongoing instability.

Time line – Key events in Myanmar’s modern history

1824–85: Three Anglo-Burmese wars led to the gradual British annexation of Burmese territory.

1886: Burma officially becomes a province of British India.

1937: Burma is separated from India and becomes a self-governing British colony.

1942–45: Japanese occupation during the Second World War, with widespread destruction and resistance.

1948: Burma gains independence from Britain; a parliamentary democracy is established, but civil war begins almost immediately.

1962: Military coup led by General Ne Win ends democracy; military rule begins.

1988: Pro-democracy protests brutally suppressed in the ‘8888 Uprising’; thousands killed.

1989: Country officially renamed ‘Myanmar’ by military junta.

1991: Aung San Suu Kyi awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while under house arrest.

2010: First elections held in decades; military-backed party wins; Aung San Suu Kyi is released.

2015: The NLD, led by Suu Kyi, wins a landslide victory; a quasi-civilian government takes power.

2017: Military launches crackdown on Rohingya in Rakhine State. More than 700,000 flee to Bangladesh. The UN calls it ‘ethnic cleansing’.

2021 (Feb): Military coup; Suu Kyi and NLD leaders detained; protests erupt nationwide.

2021 (Mar): Armed Forces Day massacre; more than 100 protesters killed in a single day.

2022–24: Armed resistance intensifies; military loses control of wide swathes of the country.

2024 (Feb): Compulsory conscription announced for young men and women, sparking mass flight.

2025: Junta clings to urban centres as resistance grows; humanitarian crisis deepens.