Neuroscientist turned environmental journalist Clayton Aldern reports on an unreported crisis in neurological health linked to climate change

By Clayton Page Aldern

In February, the Natural History Museum announced the winners of its annual Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition. The 2023 finalists had captured denizens of a natural world infrequently observed by human eyes: leaping ibexes, quarrelling Komodo dragons, nuzzling hippos, and off-gassing fungi. Yet nabbing the People’s Choice Award this year was an image familiar to many: a photograph by Nima Sarikhani, who, off the coast of Svalbard, snapped a midnight picture of a polar bear snoozing on an iceberg little more than twice its size.

If climate change has a leitmotif, surely it is Vulnerable Polar Bear on Iceberg. It is an image so seared into environmental consciousness that a whole arm of contemporary climate communications has had to mobilise for decades to remind people that global warming actually means something to them, too. The fruits of these efforts can be read today in headlines the world over. Look at those in this very magazine: ‘Climate-driven food shortages could cause civil unrest in the UK.’ ‘Coastal communities are under threat from Greenland melting.’ The climate problem is a human problem bearing on shelter, security, nutrition, and health.

But we’re still missing something profoundly intimate.

As the story of global warming has more fully embraced the human, it has become somewhat in vogue to pay lip service to the mental-health effects of climate change, among them the notion of ‘climate anxiety.’ Despite their gravity, these ideas are somewhat squishy; climate anxiety is not a diagnosis. But a focus on the mind is useful nonetheless. It orients us toward an as-yet overlooked organ squarely in the crosshairs of the climate crisis: the brain. In the brain, climate anxiety is merely the bear atop an iceberg of climate-fuelled neurological damage.

Rising temperatures, extreme weather, and ever-expanding ranges for brain-disease vectors pose staggering neurological and cognitive costs to people and healthcare systems. These costs are already accumulating today. Mosquito-and tick-borne brain diseases are cropping up in regions where they’ve never been seen before. Hurricanes, wildfires, and floods spur post-traumatic stress disorder, the treatment and productivity losses of which will cost hundreds of billions of dollars by 2050.

Neurotoxins released by cyanobacteria colonies – blooming with increasing frequency and size under climate change – offer one of the most compelling causal explanations for non-genetic cases of neurodegenerative diseases such as motor neurone disease. These effects, desperately and disparately tallied by neurologists, epidemiologists, psychologists, and behavioural economists around the world, paint a new portrait of environmental degradation: one of a public brain-health crisis that has gone largely unreported.

You’ve likely noticed you’re not as clear of a thinker when it’s hot out. It’s not just you. Cognitive deficits in the heat crop up nearly everywhere we look. Hot days regularly tank standardised test scores. Office workers aren’t as good at their jobs in the heat – and higher concentrations of carbon dioxide only make them worse. As a slow and silent poison, extreme heat inhibits our ability to learn. Recently, a group of economists in the USA looked ay the impact of hot day on school student performance. They merged ‘standardised achievement data for 58 countries and 12,000 US school districts with detailed weather and academic calendar information to show that the rate of learning decreases with an increase in the number of hot school days.’

This pattern is no coincidence. Working with mice, neuroscientists in 2015 found that heat stress impairs cognition, likely due to its inflammatory effects on the hippocampus, the brain’s seat of memory. In zebrafish, proteins related to synapses and neuronal communication are down-regulated at extreme temperatures. Cognitive neuroscientists have illustrated the manners in which connections between human brain regions tend to look more randomised in extreme heat. Heat imperils thought, and it does so via direct, physical mechanisms.

It would appear these effects compound over time, and it’s in this manner that we begin to veer in the direction of public-health emergencies. Many neurodegenerative disorders – including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and motor neurone disease – are characterised in part by protein misfolding and the accumulation of these jumbled proteins in brain matter. Heat stress, in its ability to skew the balance between oxidants and antioxidants in the brain, bears directly on protein misfolding. Indirect effects are just as worrisome. As Italian neuroscientists wrote in a 2021 review article, ‘when the outside temperature varies by even one degree due to enhanced global warming, an acclimatisation process begins, causing, if prolonged, the activation of biochemical pathways ultimately linked to neurodegeneration, such as oxidative stress, excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation.’

In practice, that means with more warming likely comes more dementia – and more extreme dementia. Dementia-related hospital admissions increase with higher temperature variability, and high temperatures worsen the symptoms of such neurodegenerative diseases. Temperature regulation is already frequently compromised in patients suffering such conditions; climate change makes it worse.

The effects will likely widen existing social inequities. Exposure to extreme heat, for example, is associated with disproportionately faster cognitive decline in black people and in residents of poor neighbourhoods. Healthcare systems in areas with poor healthcare infrastructure will be hit harder than others. And it’s not just neurodegeneration. Many neurological disorders, from multiple sclerosis to epilepsy to migraines, are exacerbated by climate change.

An upstream glance is just as harrowing: The combustion of coal, oil, and gas – itself a primary cause of climate change – only further fuels the neurodegenerative fires. Far beyond its respiratory and cardiovascular effects, air pollution in the form of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) has come to be understood by epidemiologists and neuroscientists as grimly neurotoxic.

Fine particles can enter the brain through the nasal nerve, for example, and once inside, trigger chemical cascades and inflammation that chronically damage neurons. Exposure to air pollution is associated with hallmarks of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, including α-synuclein and amyloid-β accumulation. Perinatal proximity to air pollution carries with it a higher risk of autism spectrum disorder. Globally, 27 per cent of PM2.5 comes from the burning of fossil fuels. In 2021, a global team of researchers estimated that eliminating this combustion would save a million lives annually. That’s before taking brain health into account.

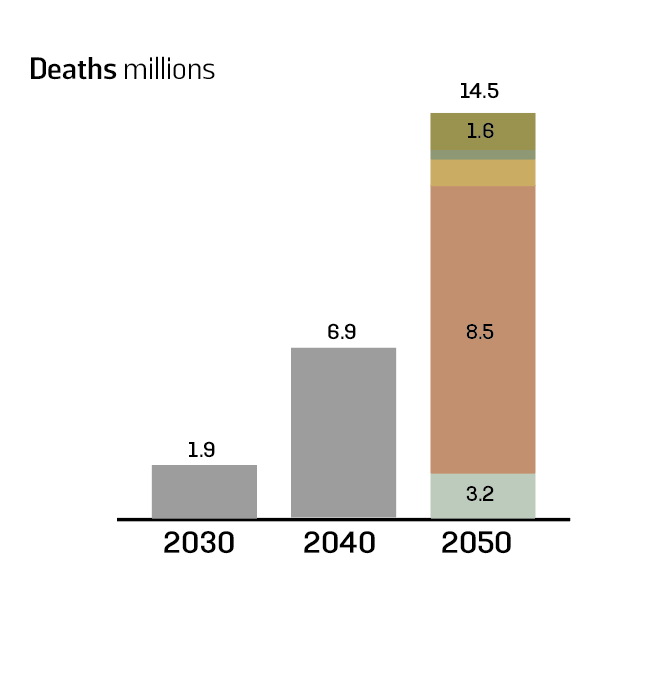

Indeed, most attempts at cataloguing the health effects of climate change and environmental degradation ignore brain health completely. ‘The cumulative death toll from climate change since 2000 will pass four million in 2024 – more than the population of Los Angeles or Berlin,’ wrote Georgetown epidemiologist Colin Carlson in a January 2024 article for Nature Medicine. His estimates, informed by turn-of-the-millenium work by Australian epidemiologist Anthony McMichael, largely focus on the health risks of malnutrition, diarrhoea, cardiovascular disease, and malaria, all of which are poised to worsen under climate change.

‘I wrote [the article] because I felt like I was the only one who had noticed,’ he shared upon publishing, referencing the body count. None of the four million deaths cited in Carlson’s paper correspond to mortality associated with brain disease. (Carlson notes in his Nature Medicine piece that the four-million figure indeed ‘might be a substantial undercount,’ in part because its underlying model ignores non-malarial infectious diseases.)

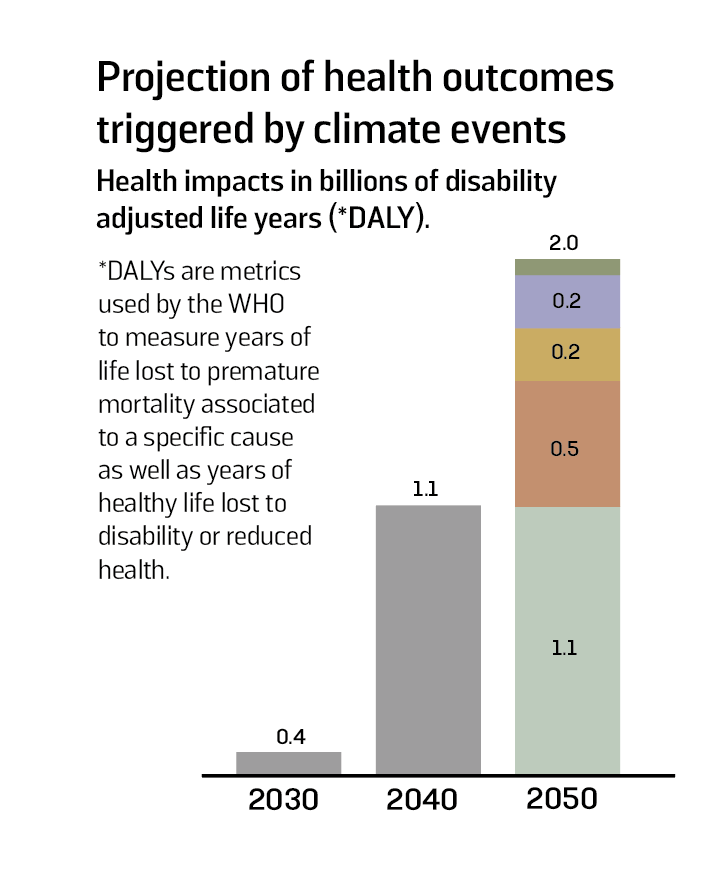

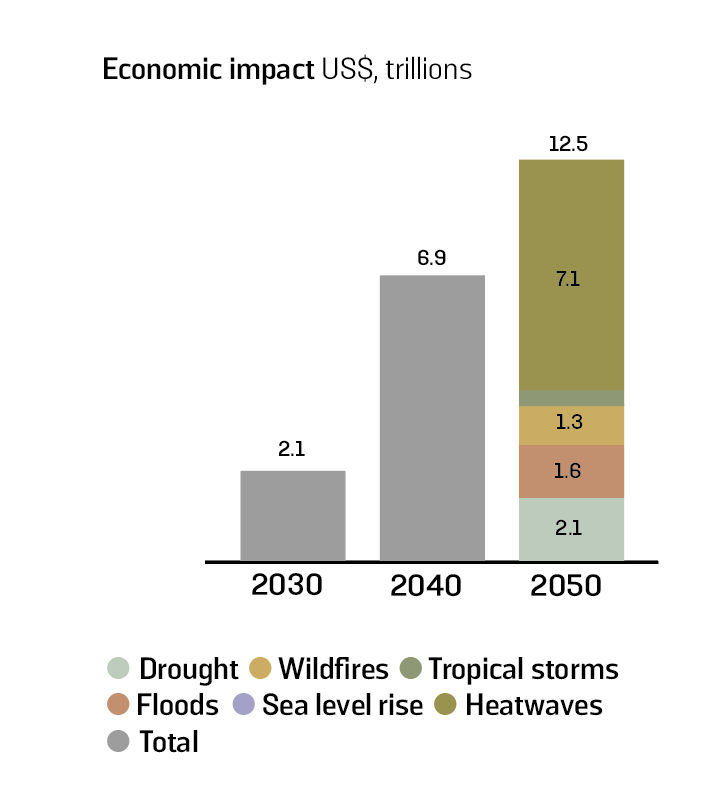

Quantifying the neurological toll of climate change is difficult but not impossible. The same month Carlson published his four-million estimate, the World Economic Forum (WEF) sought to tabulate the global health toll of a changing climate through 2050. The Forum’s report takes a similar tack to Carlson’s, summing up mortality estimates across space and time – and as an organisation with ‘economic’ in the name is wont to do, projecting the financial costs thereof. ‘By 2050,’ write the authors, ‘climate change will place immense strain on global healthcare systems, causing 14.5 million deaths and US$12.5 trillion in economic losses.’

Most compelling in the WEF report, though, is a relatively unprecedented approach to the economic costs in question. Like much contemporary climate writing, the authors gesture at the ‘mental health consequences’ of a changing climate, among them ‘anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.’ But they also attempt to price them.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is hardly a condition limited to military veterans. Wildfires, extreme droughts, floods, tropical storms – natural disasters that look more unnatural year by year are wearing on our neural fabric. In the UK, for example, a recent meta-analysis showed that 30 per cent of people suffered from PTSD in the 12 months following exposure to extreme weather events. Treatment for PTSD runs in the tens of thousands of dollars – and the WEF report authors noticed as much. They estimate that treatment of PTSD from floods and extreme rainfall alone will cost US$275 billion by 2050. Generalised anxiety disorder spurred by droughts will cost US$198 billion to the healthcare system.

These eye-popping numbers ought to catch our attention, but they need not paralyse us. The point of pricing a downstream effect of climate change is to be able to compare it with the cost of climate action. For better or for worse, policymaking runs on cost-benefit analysis, and the better we can characterise the problem – the more fully we can capture its detrimental effects – the better chance we’ll have at mitigating it.

We could start with the neurodegenerative effects of heat, carbon dioxide, and air pollution. But we can’t stop there, either. The brain diseases of climate change are manifold. Japanese encephalitis, neuroborreliosis, Zika, cerebral malaria, Powassan virus: All are set to increase in prevalence under global warming due to shifting ranges and widening active seasons of the mosquitos and ticks that carry the diseases’ underlying viruses, bacteria, and protozoa. Many of these conditions have well-characterised healthcare costs. We could catalogue them.

We could seek to understand the impacts of lesser-known climatic effects on brain health. Warming freshwater brings with it a higher likelihood of exposure to Naegleria fowleri, colloquially known as the brain-eating amoeba. Naegleria infections are frequently misdiagnosed and something of the order of 97 per cent fatal.

Warming waters also offer more favourable conditions for blue-green algae blooms, which release a neurotoxin that likely contributes to the development of motor neurone disease. Children, in particular, are vulnerable to these disease vectors, with early exposure to environmental toxins and other stressors affecting brain development and cognitive function later in life. We could catalogue these effects, too.

Recognising that climate change is acting on neurological health, today, implies that the problem isn’t an abstract one to be addressed in the future. Theorists of social change suggest that we won’t confront the climate crisis until we really feel it – until the crisis feels like a crisis; until it has some emotional resonance. Well, here it is, in that most intimate of spaces. Climate change is inside your head. The ice is melting beneath your paws, too.

In other words, understanding our neurological connection to global warming might offer a means by which we can foster a stronger emotional bond with the natural world. In doing so, I suspect we can transform nebulous concerns about future warming into tangible feelings of care and responsibility today.

Stories of resilience in and with nature, such as forests that regenerate after wildfires or communities that come together to restore coral reefs, remind us that renewal is possible. Recognising the link between our environment and our mental health, too, underscores the importance of nurturing both. Engaging with nature, whether through outdoor activities or by bringing natural elements into our living spaces, can enhance our well-being.

But a journey toward a healthier planet and healthier brains isn’t just about mitigating risk. It’s also about envisioning a future in which the relationship between humanity and nature is redefined. It’s about moving from seeing nature as something outside of ourselves to understanding it as an integral part of our being. As we navigate the challenges of climate change, we can choose to allow the emotional ties that bind us to this earth to inspire a new narrative – one that emphasises resilience, adaptation, and spirit. In the face of uncertainty, our emotional connection to the planet and to each other could wind up being our most powerful asset.

We’re only beginning to scratch the surface of a neuroepidemiology of climate change. We don’t know how bad it’s going to get, and we don’t know what it’s going to cost – in dollars or in human lives. What we do know is that climate change is not just altering our environment: It’s reshaping the landscape of brain health and public health. Walking into this future with open eyes is the only way we’re going to have any chance of doing anything about it. As Colin Carlson writes, ‘It is not too late to change course.’