By Charlotte Hall

Hurricane season has started. As powerful wind whips through the Atlantic region, most recently in the form of Hurricane Milton in Florida, images of flooded suburbs and the ruined roofs of family homes can seem hauntingly familiar.

Several record-breaking years have followed in quick succession. 2020 saw the most active hurricane season on record, with 31 storms and 14 hurricanes. 2017 was the costliest and 2022 the third-costliest season, causing devastating damage across the region and thousands of casualties.

All these records leave us with a sense that hurricanes are getting more frequent, stronger, scarier. But is that the case? Are hurricanes getting worse?

How do hurricanes form?

A hurricane is the name for a powerful swirling storm with sustained high-speed winds of over 74 m/h.

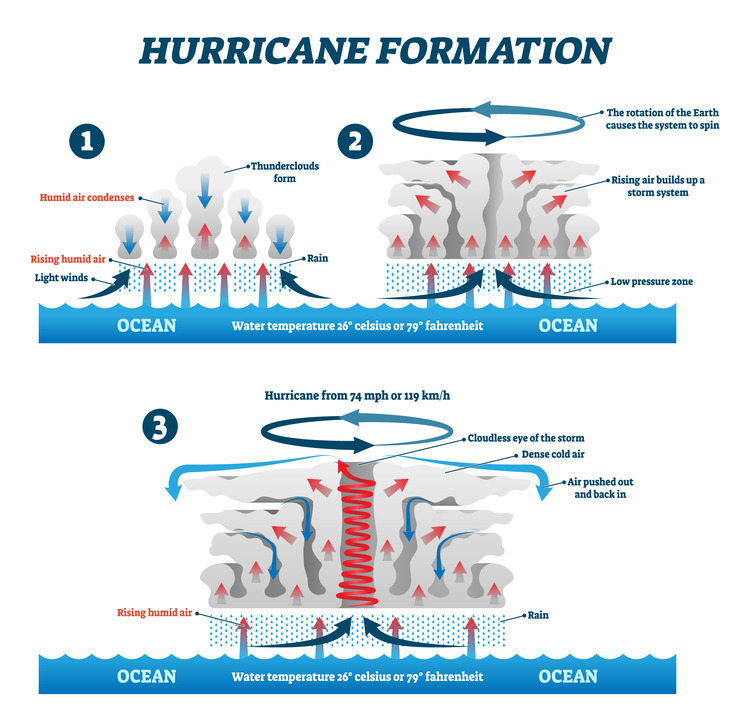

A type of tropical cyclone, hurricanes form above warm ocean water in the North Atlantic Ocean and the eastern North Pacific, often starting life as low-pressure weather systems known as tropical waves.

As this weather system moves westwards across the tropics, the warm air rising from the sea results in temporary low-pressure zones below the storm system, which are quickly filled by warm air from the surrounding areas.

Gradually, this causes the system to expand and air circulation to speed up. If winds reach up to 39m/h, the weather system is called a tropical depression. Up to 73 m/h, it becomes a tropical storm. Then, as winds continue to accelerate, the system forms a hurricane – a vertical tunnel of raging wind around a low-pressure centre known as the eye.

When hurricanes hit land, they often decelerate significantly, meaning the most powerful storms are usually observed at sea. However, when leaving the ocean they can cause a storm surge, pushing large amounts of water on-shore, causing flooding.

How are hurricanes measured?

Hurricanes are classified into five categories of strength based on maximum sustained wind speeds under the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale. Category 1 sees winds up to 95 m/h. Winds between 96-110 m/h are a Category 2 hurricane that can cause extensive damage to houses, power lines and trees.

Categories 3-5 are classed as ‘major hurricanes’. These storms are the most dangerous, ranging from 111-129 m/h at Category 3, 130 – 156 m/h at Category 4 and 157 m/h or higher at Category 5 These are the storms likeliest to cause fatalities and significant damage to buildings.

Hurricane Patricia in 2015 is the strongest Category 5 storm on record, with maximum sustained winds of 205 m/h. Luckily, it quickly weakened as it hit land and dissipated into a tropical storm within 24 hours.

Another important measure of hurricanes is barometric pressure. The lower the barometric pressure, the more intense the hurricane. As pressure increases, hurricanes lose strength and eventually peter out.

Hurricanes are becoming more frequent

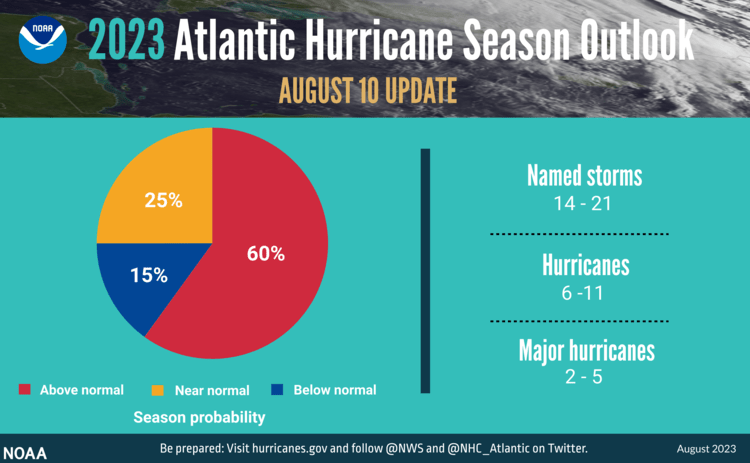

Each year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration makes predictions about the incoming hurricane season. In May, experts predicted that 2023 would see a ‘below average’ season.

Yet after rolling out a new hurricane modelling software a month later, NOAA quickly revised its verdict. In August, it issued a statement increasing the likelihood of an ‘above average’ season to 60 per cent.

Scientists are now expecting 14-21 named storms with 6-11 major hurricanes. The average is 12 named storms and three major hurricanes.

If their predictions are correct, 2023 will become the eighth year in a row of above-average hurricane activity, with only 2022 having shown ‘near-average’ numbers of storms.

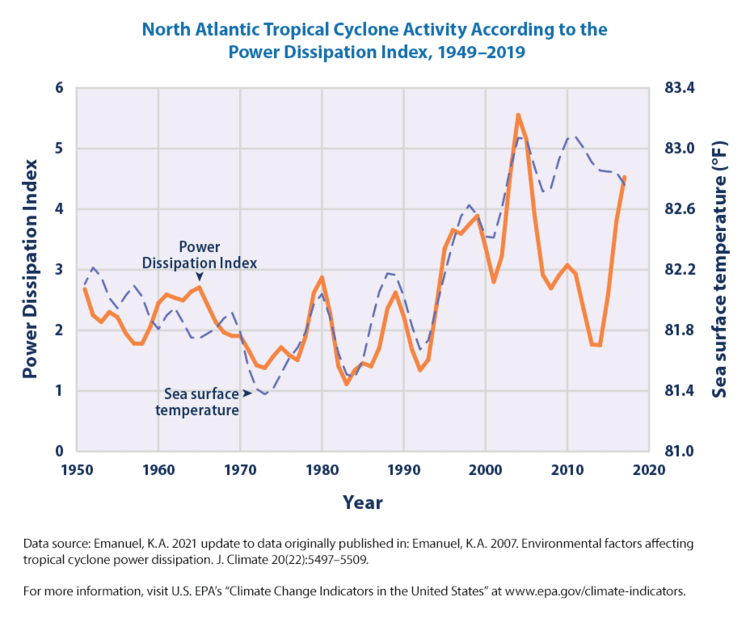

When plotted on a timeline, the annual number of hurricanes shows a rising trend since the 1950s, with a brief interruption in the 70s and 80s known as the ‘hurricane drought’.

At a more conservative estimate, relying on more reliable data supplied by satellite and aerial monitoring since the 1970s, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) points to a noticeable increase in cyclones since 1995.

The increases could be linked to rising sea temperatures.

Rising sea temperatures are wreaking havoc on weather systems

Greenhouse gas emissions trap heat close to the earth’s surface. Around 90 per cent of that excess heat is absorbed by the ocean, according to research by the National Centers for Environmental Information.

With some parts of the ocean already 1.5 degrees hotter than in 1901, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution notes that weather systems are likely to be impacted across the globe.

‘Rising ocean temperatures are making some extreme weather events worse by supercharging storms and altering global weather patterns,’ the institution wrote in a statement. ‘Warm surface waters provide energy for hurricanes and other tropical cyclones, increasing their frequency and severity.’

Ocean warming happens at an irregular rate across the globe, but the North Atlantic contains a number of hotspots. While there is no conclusive evidence that these higher temperatures are causing an increase in the number of storms, the hotspots mean that it has become more likely those storms will turn into hurricanes.

That’s because with higher temperatures, the wind speeds in those weather systems are likely to accelerate faster.

Hurricanes are getting stronger and more intense

But the biggest concern for scientists is that hurricanes appear to be getting stronger, more intense and harder to predict.

A study by the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen found that the proportion of major hurricanes (category 3-5) in the Atlantic Ocean has doubled in the last forty years.

Hurricanes are also intensifying at a faster rate each decade and at widely varying rates, which makes them challenging to anticipate. Hurricanes Dorian and Laura in 2019 and 2020 both suddenly intensified close to landfall, leaving many people unprepared for the devastation that followed as they coursed through the Caribbean.

Hurricanes are becoming wetter

Rising ocean temperatures could be causing another major development in the character of hurricanes: they are getting significantly wetter.

Storm systems pick up more liquid due to the increased level of evaporation over hotspots in the Atlantic, which are promptly dumped in the region around the hurricane in the form of thunder and rainstorms.

Storm Idalia dumped three months’ worth of rain onto the Nevada desert last week, transforming the site of the Burning Man festival into bogland.

On top of this, sea levels rising as a result of human-caused global warming are exacerbating the risk of flooding caused by storm surges.

When Hurricane Katrina destroyed the New Orleans area in 2005, it was the storm surge that caused the most damage, as flooding broke through the local levees.

Sea levels have risen by 8-9 inches (21-24 centimetres), according to NOAA. The higher the sea level, the more vulnerable coastal areas are to flooding.

Hurricanes are getting longer

One study also found that hurricanes have become slower to dissipate. Once, tropical cyclones were expected to die down quickly once they hit land. But over the last 70 years, the time it took for a hurricane to ‘decay’ has increased by 10 per cent, causing more sustained damage to coastal areas.

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey exploded into a major hurricane lasting 37 hours. The continuous storm brought down 40 inches of rain in some areas, causing widespread flooding and over a hundred deaths.

Though the area is under-researched, the authors of the study suggest these new durations could also be linked to climate change.

The leading theory, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, is that warmer climates slow down the winds that steer hurricanes across land and sea.

How to survive worsening hurricanes

In short: hurricanes are getting worse. They are becoming longer, more intense, more frequent and more damaging.

These are not findings that inspire optimism. So, is there anything we can do about worsening hurricanes?

Institutions such as the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions note that the most crucial step in limiting the long-term harm of hurricanes is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions immediately.

Communities and city planners can also create initiatives to restore and preserve coastal wetlands, dunes and reefs to absorb storm surges. They can also build storm protections like elevated buildings, seawalls and wind-reliant houses.

And local authorities should have emergency plans and guidance in place, even in areas currently at a low-risk of being affected by hurricanes.

In the words of Nasa, the best thing you can do against hurricanes is ‘be prepared‘.