The melting of the Greenland ice sheet poses a unique challenge for its coastal communities

By

Meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets is causing unavoidable sea-level change, yet while much of the world prepares for an increase in flooding, Greenland is facing a very different future. ‘Most people think the loss of ice means sea-level rise,’ explains Margie Turrin, ‘but actually, around Greenland, that means falling sea levels.’

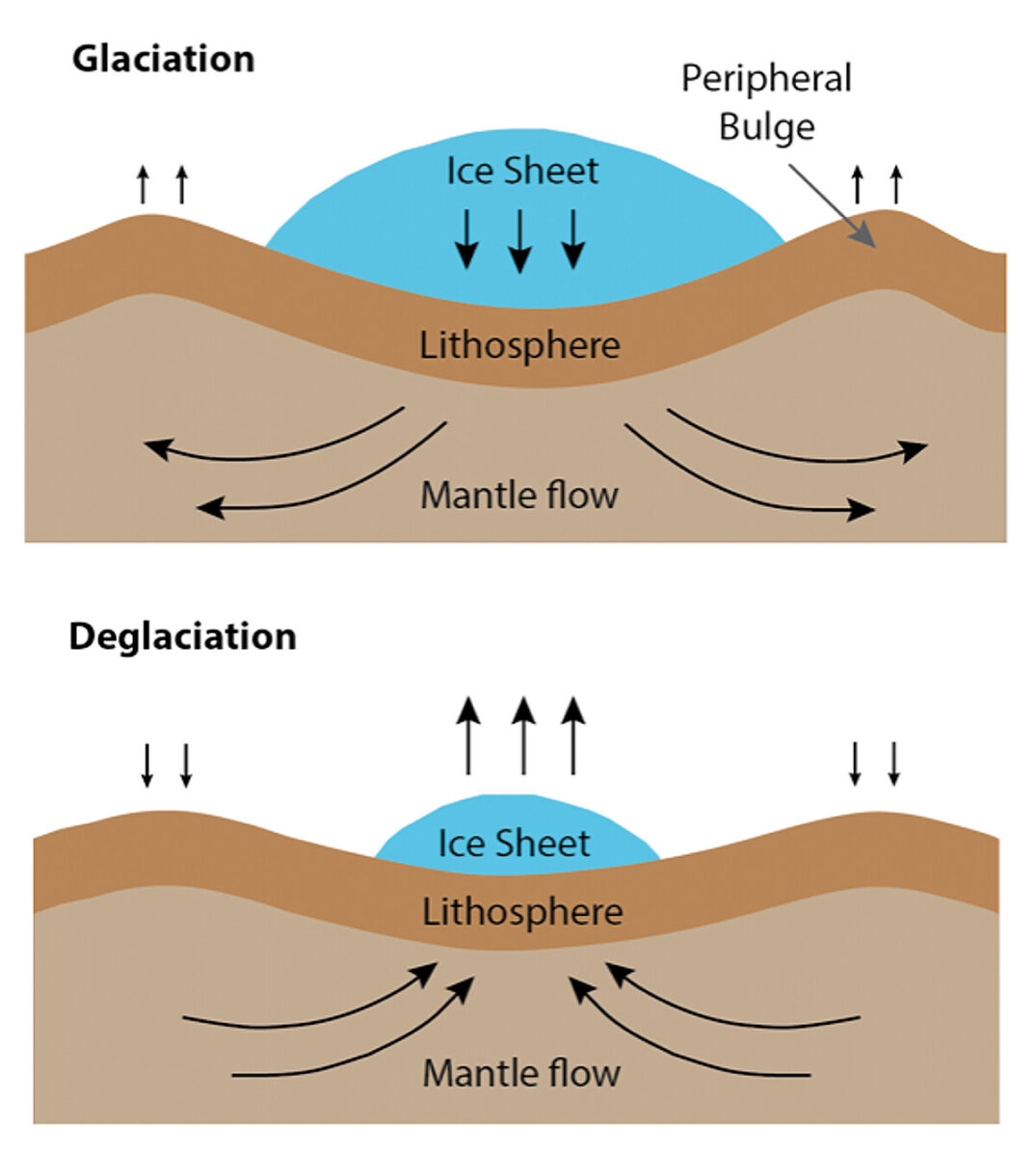

Turrin is the director of educational field programmes at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, where she works on the aptly named Greenland Rising project. Its aim is to understand the changes taking place along Greenland’s coast, where local residents have reported seeing rocks emerging from the water. In reality, that’s not too far from the truth. What’s currently happening in Greenland is largely a combination of two processes. As the ice sheet loses mass, it exerts less gravitational attraction on the sea surface around it, causing the water to drop away. At the same time, the reduced weight of the ice sheet, which has pushed down on the solid land below it for thousands of years, is now allowing that land to slowly spring back (a geologic process known as isostatic rebound), pulling the coastlines up out of the sea. The Greenland Geodetic Network, which has been measuring the post-glacial rebound using a network of 58 global navigation satellite system stations in bedrock around the island, has documented uplift rates of up to 23 millimetres a year.

Greenland isn’t the only place experiencing a decrease in sea levels; similar processes are taking place in Antarctica, the location of the Earth’s only other ice sheet. What makes the situation in Greenland unique, however, is its permanent population. As in many other regions, the ocean is a major resource for Greenlandic people. Yet, unlike in the rest of the world, Greenland’s landmass remains largely covered by thick ice that spans 80 per cent of its territory. ‘In Greenland, settlements are on the coast,’ says Turrin. ‘So the people there are dependent on the ocean for their livelihoods – fishing and hunting, as well as transportation of people and supplies.’ Coastal infrastructure, shipping routes and natural ecosystems will all be affected by the land rise. ‘Already we’re seeing challenges for the passage of ships in some areas, and more will occur as we go forward.’

The team at Columbia University has been working closely with the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, which has facilitated communication with local communities to measure and map the shallow waters around the coast. Long-term tide records are few, and local community knowledge has been invaluable in identifying hotspots for future change, as well as understanding the needs of community members. There has been a concerted effort to involve the people in the region and avoid what Turrin terms ‘extractive science’. ‘It’s all too easy to go in with your own science questions, collect the data and leave. We’ve really worked hard to make this relevant to the communities where we’re actually collecting the measurements.’

For now, the project has focused on three communities on the west coast: Kullorsuaq, a fishing town; Aasiaat, a hub for tourism and shipbuilding; and Nuuk, Greenland’s capital and its cultural and economic centre. The maps they’ve co-produced, and made freely available, are already being used by fishermen to navigate to deeper pockets of water for their catch. Hopefully, says Turrin, the research will also help the communities plan for changes to their ports and other infrastructure. While every community will be affected differently, the biggest changes are yet to be faced by the residents of Kullorsuaq, the northernmost settlement, where ice loss is – so far – less pronounced.