Colombia is one of several global biodiversity ‘darkspots’, but local scientists are now discovering plant species on newly accessible land

By

Looking at the tiny, yellow petals of the flower in front of them, Heidy Caro and Susana Arango immediately suspected they had found something special. Standing among the remnants of a Colombian oak forest, in the Eastern Cordillera mountain range, they snap photos of the plant to send to their colleague Eugenio Restrepo, a botanist at the University of Caldas. His response suggests the same thing: a newly discovered orchid.

Covering nearly 1.15 million square kilometres of land (4.3 times the size of the UK), Colombia is home to a wide variety of ecosystems that support some of the greatest biological diversity on the planet. Mangroves, beaches and river estuaries run the length of its Caribbean coast, while rainforests, wetlands and savannahs border Brazil.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

But it was the relatively recent rise of the Andean mountains, some 15 to 20 million years ago, that led to the mass evolution of Colombia’s orchids.

Today, Colombia has the greatest diversity of orchids in the world, with nearly 4,270 species known to science. Experts think there could be many more. In fact, new research from scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew identifies Colombia as one of 33 global plant biodiversity ‘darkspots’ – regions that are teeming with plants, thousands of which are still unknown to us.

That’s a problem when an estimated three in four plants are threatened with extinction, says Kew scientist and orchid expert Oscar Pérez- Escobar. ‘If you don’t know what’s out there, you don’t know how best to preserve it.’

Knowing how many plant species are yet to be discovered poses researchers quite a challenge.

‘In all honesty, it’s a very difficult process,’ says Kiran Dhanjal- Adams, a conservationist and expert in ecological modelling. ‘There are lots and lots of stats going on here.’ To get a better idea of the number, Dhanjal- Adams and her colleagues at Kew looked at species that were already known to science, and considered how long it took to describe them and how long until that same species was found somewhere else. They also took several other factors – such as a plant’s range size and life form – into account.

‘Think about a tree,’ she says, ‘they’re very big, they’re there all the time, they’re easy to spot. Compare that to a species that only pops up for a short period of time, like a daffodil, or one that only grows high up in the canopy, like an orchid. If we’ve already described a lot of orchids and trees in a region, we’re probably further along the discovery curve than if we’re still describing new tree species.’

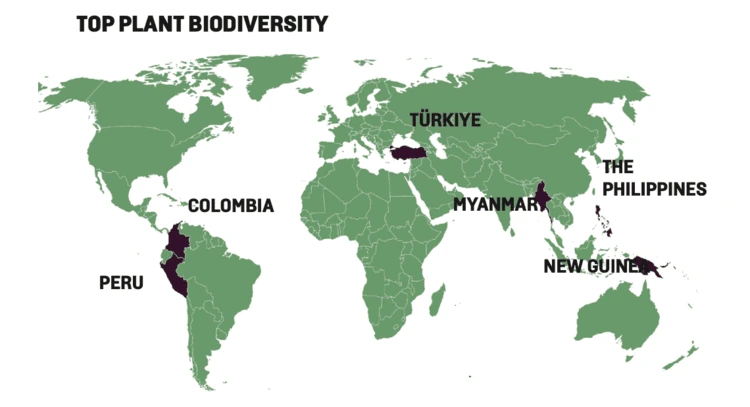

Dhanjal-Adams says the results of her research can now help scientists decide where to prioritise plant collection and fill some of those gaps in our knowledge. Of the 33 ‘darkspots’, six consistently came out as focus areas for focused collecting activities: New Guinea, the Philippines, Myanmar, Türkiye, Peru and Colombia.

Knowing where to look, however, is just the beginning. Pérez-Escobar, who is currently identifying a new species of Colombian orchid first spotted in 2021, laughs when asked how it’s taken him three years so far.

On average, he explains, it takes 70 to 100 years. New species aren’t always easy to see, even when they’re growing in plain sight. ‘There was a very interesting case study at Kew, the Victoria boliviana, a species of giant waterlily,’ says Dhanjal-Adams. ‘It had been at Kew for many, many years, but it’s only just been described.’

A lack of funding and challenging landscapes are major hindrances to plant discovery in Colombia and many other biodiversity ‘darkspots’. It took Arango, a biologist from the University of Antioquia, nearly 20 hours to reach the site she would be studying from her home in Medellín, travelling on very long and bumpy roads. Once there, she and Caro had to navigate the steep sloping terrain that had protected the old oak forest from the expansion of the pastures surrounding it. ‘We faced a lot of challenges – we’re students, we have very limited resources.’

Until fairly recently, Colombian researchers also have had little access to many parts of the country. ‘We were at war until 2016,’ says Pérez-Escobar, whose field trips to Colombia’s Boyacá region in 2017 were still conducted under army escort. Since Colombia’s FARC peace agreement, however, the annual number of local plant species discoveries has tripled. ‘There really is a before and after the agreement’.

In September, Caro and Arango published a paper on the newly discovered orchid species, Lepanthes garciarovirensis, that they found in the Eastern Cordillera. They’re working on describing another two species, found nearby. Arango is relieved that the hard work, and more than a few disappointments have paid off. ‘It’s a very exciting time for us,’ she adds