Find out more about climate models, how they work, and the accuracy to which they can forecast future changes on our planet

By

Climate models are everywhere. These mathematical models help us to navigate and better understand the future of our planet, influencing policies and behaviours on international and local scales around the world.

But what exactly are climate models, and how do they work? Can such predictions be right all the time?

What are climate models?

A climate model is a computer program made up of thousands of lines of code that can simulate weather patterns over an extended period of time.

Essentially, these models, also known as general circulation models (or GCMs), use mathematical equations to predict how energy and materials will behave in the Earth’s climate. All climate models incorporate concrete physical laws into their calculations, such as the conservation of energy and how water and air move, to ensure that predictions made are realistic.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Climate models can take on a variety of forms, from those covering one region or country to models that simulate the entire atmosphere, ocean ice, and the entirety of Earth’s land.

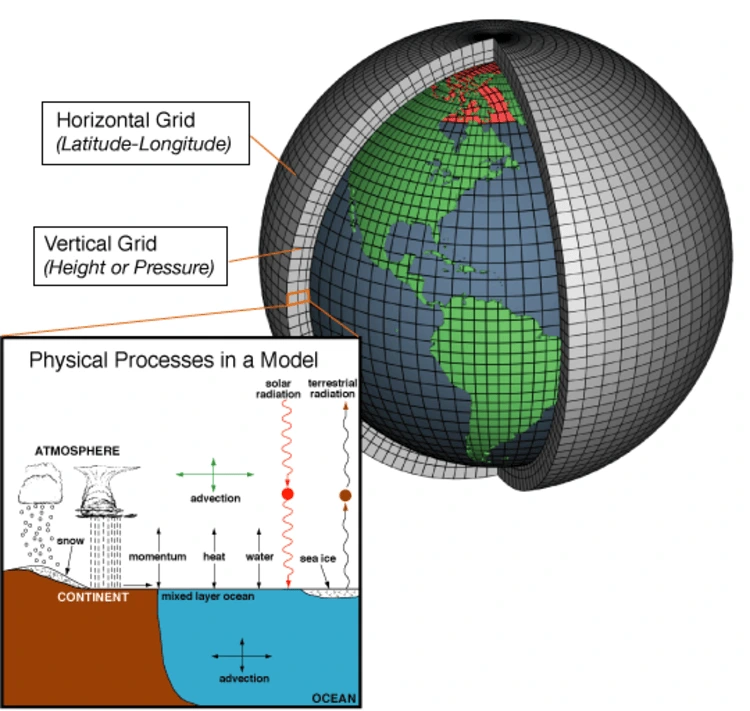

They work by separating the Earth’s surface into a three-dimensional grid, with each compartment known as a ‘cell’. The size of the grid affects how detailed the climate model is: the smaller the grid size, the higher level of detail. Running these more detailed models requires the support of huge supercomputers the size of a tennis court. Such models can also take a long time to run as more calculations will need to be made for each individual cell.

Grid sizes used to be around 200km by 200km, but due to advances in technology, they can now be as small as 25km by 25km, allowing for scientists to see the likelihood of individual weather systems, such as storms, occurring.

Each cell in the grid is analysed over a time period, creating a greater picture of how matter and energy interact across a particular region or area.

Despite the plethora of models that exist – with varying individual, specific predictions – climate models do universally agree on a set of factors: human activity is causing the climate to change, and both sea levels and average global temperatures will continue to increase.

Are they accurate?

To test if a climate model is accurate, scientists can run simulations of past events into them, to see if these models predict the same weather event, pattern or outcome that actually did happen. This process is known as a ‘hindcast‘, an opposite term to ‘forecast’. Many climate variables from hurricane formation to sea ice extent have been correct, showing that these models can be relied on to simulate accurately for the most part.

A recent study, which looked at a range of climate models – some 50 years old – also found that their forecasts accurately predicted global surface temperatures. However, despite their positive track record, by nature of the fact that climate models are predictions, they cannot be perfect all of the time.

In some cases, models may be incorrectly predicting a ‘worse’ future than expected.

Due to using newer metrics, some climate models overestimated the extent of coral bleaching as a response to heat stress, showing anywhere from 33 – 1,584 per cent more bleaching events compared to models with the previous, well-validated metric.

Another example, recently noted, is that certain models are forecasting a future in which the Earth is warming at faster rates than in reality, ‘exaggerating’ the impacts of global warming. A reason for these incorrect models is due to the way in which they have rendered clouds, a notoriously difficult weather pattern whose effects are not universally agreed upon.

Some climate models believe clouds will worsen warming, while others think they play a neutral – or even positive – role in helping to curb rising temperatures. As such, these differences give rise to models with very different conclusions on particular scenarios.

To counter this, rather than scientists using averages from all climate model projections – which can lead to global temperatures being 0.7C warmer by 2100 than estimates from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – experts are advising a choosier approach to models, prioritising those with more realistic warming rates. This way, climate models can retain as much accuracy as possible.

Another factor that impacts the reliability of models is that of inputted forecasts. For example, scientists are unsure as to the exact rate of greenhouse gas emissions falling in the future, so will make different predictions, adding further ambiguity to the conclusion of various climate models.

Although some climate models may have predictions or forecasts that are slightly off, it is important to note that the scientific understanding of the Earth’s climate remains rooted in the same indisputable fact: greenhouse gases are warming the planet, leading to ice melt and sea level rise.

Improving climate models

One of the best ways to improve climate modelling is to increase computing power: in doing so, scientists can up the resolution of models and make them more detailed at both regional and local levels. Additionally, refining computing power will allow climate models to run at faster rates – as some currently take months to complete – meaning more information and predictions about the climate’s future can be made in a shorter period of time.

Collecting better observational data on the atmosphere and oceans can also help improve climate models. Currently, they are based on data from the last few decades, but since the Earth’s climate is ever-changing, having more recent knowledge of our planet’s state can make future understandings of our climate even more robust.

Machine learning and AI can also aid models, analysing data at much greater speed than before and creating patterns that may not have been observed before. Together, machine learning and AI may make it easier to represent more difficult-to-model processes like turbulence and cloud formation.