Kit Gillet reviews Africa is Not a Country: Breaking Stereotypes of Modern Africa, by Dipo Faloyin, published by Harvill Secker

‘For too long, Africa has been treated as a buzzword for poverty, strife, corruption, civil wars and large expanses of arid red soil where nothing but misery grows,’ writes Dipo Faloyin in Africa Is Not a Country. Either that, or the continent has been viewed as one big safari park.

Africa Is Not a Country aims to set that record straight, while also painting a portrait of modern Africa as it is today – a bustling, generally thriving continent of 54 countries and 1.4 billion people. Yes, there are dictators, but there are also stable democracies, a growing middle class and plenty to feel positive about.

Lagos, Nigeria’s unofficial capital, is home to more people than London, New York and Uruguay combined, and is a city that ‘commands waves of raw energy that require you to adapt or stay at home,’ writes Faloyin. Africa is filled with other places that deserve our attention, rather than our pity – although, of course, there are reasons to pity the continent.

Modern Africa was designed against its will to be a divided thing, writes Faloyin. In the 19th century, European powers carved up the continent, notably at the 1884 Berlin Conference, where countries such as Britain, France, Portugal and Belgium literally partitioned up Africa without any real understanding of what the realities were on the ground. At the time of the conference, 80 per cent of Africa was free; within the next 30 years, 90 per cent of it would come under European control.

Many of the arbitrary borders established by the European powers would later lead to conflicts, as independence movements swept across the continent in the 1950s and ’60s. In fact, 60 per cent of all territorial disputes that have gone to the International Court of Justice come from Africa, despite only 30 per cent of all borders in the world being on the continent. At the same time, according to a 2011 study, nine of the 13 most arbitrary states in the world are in Africa, including Chad, Equatorial Guinea and Eritrea.

Faloyin recounts some of the more painful episodes of Africa’s recent past, including the rule of Somali dictator Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who came to power in a bloodless coup in 1969 but later instigated a purge of a rival ethnic group that left an estimated 200,000 dead and created 300,000 Somali refugees; and that of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, which caused extreme pain and suffering. Sadly, ‘authoritarians very rarely go down without taking their entire country with them’, Faloyin writes.

Even so, African nations aren’t predisposed to evil despotism, and today, only ten per cent of the continent is under authoritarian rule. Instead, many countries have vibrant democracies, thriving cities and growing middle classes who enjoy much the same activities and interests as people in other regions of the world.

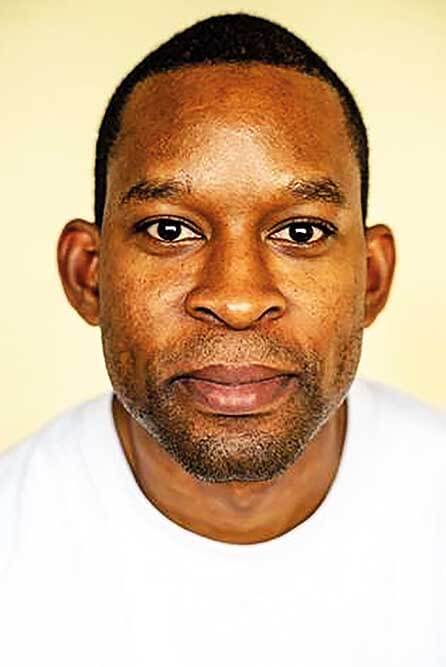

Africa Is Not a Country charts the history of the African continent and many of its countries; however, it isn’t a history book. Rather it’s a book about the current realities on the continent. As such, Faloyin is a good choice to write it. A senior editor and writer at VICE, he was born in Chicago but raised in Lagos in a sprawling Nigerian family; hence, he sees the continent from the position of both an insider and an outsider.

One thing that becomes clear when reading Africa Is Not a Country is that there are huge differences between countries on the continent, both in geography, history, culture, language and prosperity. Nigeria is as different to South Africa or Ghana as Poland is to France or Portugal. Sadly, many of us continue to lump them all together. This is true in news coverage, as well as novels, Hollywood portrayals and even charity campaigns.

Faloyin has no intention of being a dispassionate observer, or of trying to maintain a neutral tone. Instead, he goes after the issues that particularly offend him (and many in Africa). One of the biggest is the way in which Western charities often portray the continent. While charity efforts to support various parts of Africa have raised tens, if not hundreds of millions of pounds over the years, they often do so by relying on a series of lazy stereotypes.

Faloyin takes particular offence at the song ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ – released back in 1984 for Band Aid to help anti-famine efforts in Ethiopia. The song, a modern Christmas classic, paints Africa as a place of dread and fear, where nothing grows, ‘condensing all the worst stereotypes of the region as one large failed state into a pleasant four-minute jingle,’ Faloyin writes. Among other glaring inaccuracies, Africa has more Christians than any other region of the world, he adds.

Africa Is Not a Country also charts the fight to regain Africa’s cultural treasures, many of which were removed from the continent, often by force, over the years of European control. According to the book, 90 per cent of Africa’s material cultural legacy is still kept outside the continent, and attempts to retrieve it have largely fallen on deaf ears. Particularly notable are the Benin Bronzes, which are still primarily held by the British Museum.

The book also delves into more unusual (and colourful) controversies, such as the fight over the right way to make jollof rice, a ubiquitous dish across much of West Africa. At one stage, celebrity chef Jamie Oliver wades into the conflict, offending many in the region with his own take on the dish.

At times, Africa Is Not a Country can come across as too much of a diatribe, albeit one with a strong justification. ‘Africa has always been treated more as an idea than a place,’ Faloyin writes. ‘An ideal of suffering and struggle. An idea of violence. An idea of cursed leadership. An idea of a great weakness that can easily be exploited and stripped of its assets.’

It’s time to change that.